A book newly acquired by the Thammasat University Libraries explains what can be expected in the building and development of libraries in future. The Library Beyond the Book is by Jeffrey T. Schnapp and Matthew Battles, director and associate director of metaLAB (at) Harvard, a research and teaching unit at Harvard University exploring networked culture in the arts and humanities, especially the digital humanities. Dr. Schnapp is also faculty co-director of the Berkman Center for Internet and Society, a research program at Harvard Law School founded to explore cyberspace. Dr. Battles is author of Library: An Unquiet History, which is not in the TU libraries collection but which may be obtained by interlibrary loan. Both authors are insightful and prestigious thinkers on libraries and research subjects, and they reject the practicality of a library without books. Printed books will always play a role in libraries of the future, which will not be completely virtual, or only dealing with e-books and the like. Libraries will certainly continue in different cultural and architectural forms. Based on research about technical innovation at metaLAB, The Library Beyond the Book examines past libraries to find that the future rests in hybrid collections that mix printed books and e-books. As Dr. Schnapp describes the message of his book:

Throughout history, Matthew and I argue, libraries have been sites for new media, new technical demands, and new cultural forms, that have encompassed an array of typologies that build into future scenarios for the library after the book. These scenarios include:

the Mausoleum—a place to commemorate and commune the dead

the Cloister–a refuge for reflection, meditation and contemplation in shared solitude [Neocloister]

the Database—a container for information that is classified, accessible, controllable, infinitely expansible

the sort of Warehouse where the willy-nilly proliferation of documents and stuff is rendered navigable thanks to computational supports and machine eyes [The Accumulibrary]

a Material Epistemology, where collocations and consanguinities among different kinds of knowledge are proposed, experimented with and affirmed [The Programmable Library]

and a series of Libraries of the Here and Now untethered to collections, from Mobile Vectors to Civic Spaces (where public ties are forged and affirmed) to freestanding Reading Rooms as spontaneous, popular, insurrectionary responses to closed and controlled versions of all of the above.

Such library types have been mixed and matched in the past, and we argue that remix remains the most plausible future scenario.

Thai libraries.

These conclusions are especially significant for Thailand, where unlike other Asian countries, especially Korea, recent studies have shown that readers still prefer reading printed books, rather than e-books. In addition, surveys have proven that Thai men in general are more worried and anxious about computers than are Thai women. For these reasons and others, to assume that printed books will soon become obsolete in Thai libraries would be premature, to say the least. Despite the welcome presence of iPads for student use in university libraries, Drs. Schnapp and Battles call for new and forward-thinking libraries to include architectural spaces containing paper as well as pixels. Bookshelves, card catalogs, librarians, and reference desks are valuable elements of the past which can be carried on to the future usefully. Trying to make everything virtual will not succeed or serve the public in the best way. The Library Beyond the Book presents an imaginative variety of future libraries as study shelters, mobile libraries, reading rooms advancing social change, and knowledge centers based around specific events. They argue that books have never been just books, and libraries have never been just libraries. Both serve multiple complex functions.

Saving libraries.

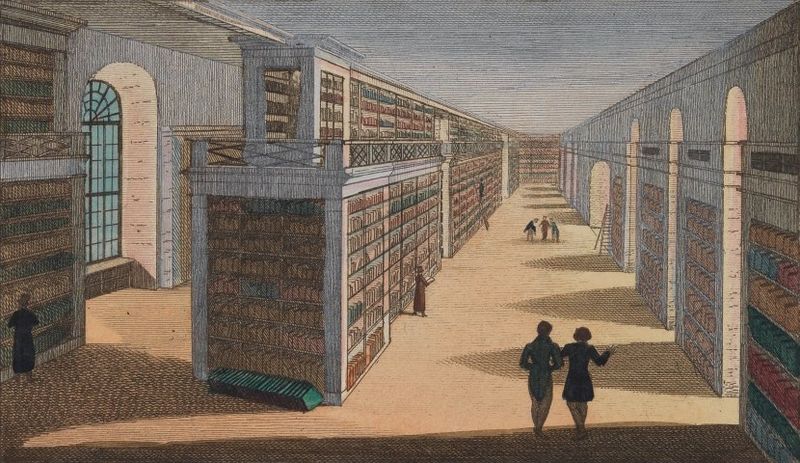

Faced by budget cuts and other threats, libraries must find innovative solutions to ever-increasing problems. Harvard students under the guidance of Dr. Schnapp have created innovative design ideas in a Library Test Kitchen. This laboratory class at the Harvard Graduate School of Design resulted in such concepts as a literary mix tape where students can print on demand a selection of texts that they want or need to see in a single bound volume. A table making white noise was designed for readers who are bothered by total silence in a library setting. Harvard is a good place for such cutting-edge notions, since the university’s library system must deal with a collection of over 17 million books. Although Harvard, like many other universities, has announced a plan to reduce library staff and provide more digital access rather than acquiring printed and other physical materials, this approach has been widely criticized by scholars and librarians. The Library Beyond the Book provides welcome context by offering the history of research libraries, reaching back some 2,500 years to The Royal Library of Alexandria in Egypt, one of the most important libraries of the ancient world. For now and the future, preserving and exchanging knowledge is a key goal while keeping up with – and anticipating – library users’ need for technology on demand.

Cutting costs.

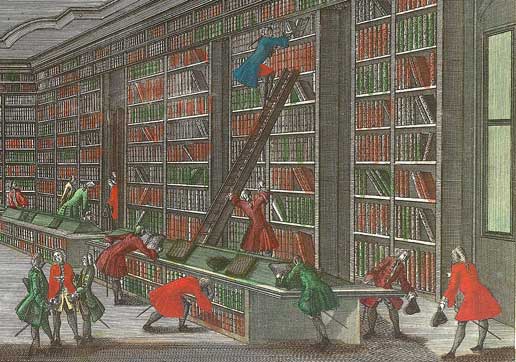

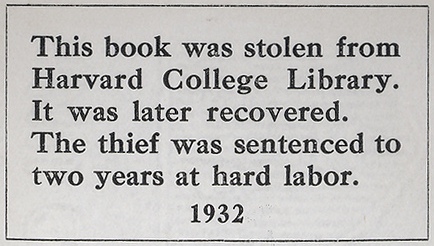

Getting rid of book stacks and digitizing, while a fashionable approach that saves money in the short term, has been seen by many as a short-sighted and counter-productive approach. The Library Beyond the Book reminds us that not every innovation is a flawless idea to be followed unthinkingly and uncritically. The University of Chicago’s Joe and Rika Mansueto Library, opened in 2011, has no open stacks. Its books must be requested online. Robotic cranes obtain the books for users. While this may have an appealing futuristic look, many library users around the world protest when open stacks are closed. As all readers know, sometimes even serious researchers can make unexpected finds by browsing on open shelves. If you must know what book you are looking for in order to request it, you eliminate most of the possibility of a chance or unexpected discovery. This limits research results. Even for less serious researchers, wandering through open stacks and taking a book off the shelf at random is a fun way of making new discoveries and learning. By closing stacks and requiring all book requests to be made online, libraries are sending out a message, even if unintentional, that such fun and sometimes valuable discoveries are not important. All that matters is fulfilling online requests. To some degree, this bureaucratic-minded approach makes the job of the librarian much easier, but it also reduces the scale and scope of research and the definition of what a library can be. The Library Beyond the Book and the research labs that are behind its suggestions are in favor of expanding the role of libraries, not contracting it. That means adding new things and juxtaposing them with old ones, rather than eliminating time-honored features of libraries. So recently, when the Welch Medical Library of the Johns Hopkins University eliminated public workspaces entirely, many people were surprised. Instead of being a place to study, this medical library now just delivers books requested online to campus offices and mailboxes some days after the request is made. Students and faculty can email or call library staff, but if they want a place to work, they are sent to campus lounges and study rooms. This approach can seem odd, even for the well-funded Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, where fortunate students have alternatives places to study. In less privileged countries where students desperately need quiet places to work on academic assignments, this kind of decision could harm their overall educational experience.

Last year under great pressure, the New York Public Library abandoned a controversial Central Library Plan which would have removed some two million books from underground stacks and sent them to a storehouse in New Jersey. Then the library would have been remodeled as a lending library. This idea outraged many librarians, researchers, and experts in architecture. They argued that requiring researchers to wait some days for requested books – as is currently the case in the Johns Hopkins medical library – would harm the library’s level of service. However difficult it may be to manage open access, onsite book stacks, their full value is truly appreciated only when they are threatened with elimination.

The Library Beyond the Book is a timely reminder for librarians not to mistake the current and future importance of digital information for some kind of ban on printed books. Printed books are not easily disposed of, and librarians who are too eager to do so might consider the effect such a policy will have on future generations of library users.

(all images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)