Just in time to help celebrate his 75th birthday earlier this month, the Thammasat University Libraries have acquired Studies in Thai and Southeast Asian Histories by Charnvit Kasetsiri. The TU Libraries own many other books by the renowned historian, who has an exemplary record of service to the university.

After graduating in 1963 from Thammasat where he studied diplomacy and history, Ajarn Charnvit earned a master’s degree at Occidental College in Los Angeles, California and a Ph.D. in Southeast Asian history from Cornell University in 1972. Returning to Thammasat to work with Dr. Puey Ungphakorn, Ajarn Charnvit was consecutively a lecturer in the History Department, dean of the department, deputy director of the Thai Khadi Institute, Thammasat University (1982–85) and vice-president of Thammasat University (1983–88). He also served as dean of the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Thammasat University, while continuing to lecture in history, and was ultimately named rector of Thammasat University (1994–95). He donated his archives and personal library to TU and the TU Libraries, and a special room of the Pridi Banonyong Library, Tha Prachan campus is named in his honor, where students gather to prepare assignments and occasionally browse on the shelves among books that were once read by Ajarn Charnvit. Among his international honors is the Fukuoka Prize 2012 for academic achievement.

Studies in Thai and Southeast Asian Histories is unique as a self-portrait of a wise and charming historian and thinker about history, especially as it applies to human lives today. There are many different articles on such subjects as the history of Ayutthaya, one of Ajarn Charnvit’s great specialties, as well as ASEAN countries, border issues, and related matters. Because it is precise, done with brilliant technique, and often witty, this self-portrait reminds the reader of one of the extremely fine French pastel portraits of the 18th century, by artists such as Maurice Quentin de La Tour. The ability to remain good-humored even in the face of serious and challenging questions was one of the attributes of Ajarn Charnvit’s mentor, Dr. Puey Ungphakorn. Ajarn Puey is one of a group of seven historians to whom the present book is dedicated by the author. Ajarn Charnvit states that they “inspire me in their different ways,” and they are a disparate bunch. All share deep and detailed understanding of Southeast Asian history, but also an ability to generalize about the region and the wider world. Their useful conclusions sometimes serve as remedies or strategies for situations. One of these scholars who is still thriving is Professor Wang Gungwu, who will be 86 later this year. An Australian historian of Asia, Professor Wang is an expert on the migration of Chinese from their native land. Born in Indonesia and raised in Malaysia, Professor Wang has an unusual grasp of ASEAN issues. Others among the dedicatees of Ajarn Charnvit’s book were illuminating teachers at Cornell, including the British scholar Daniel George Edward Hall (1891-1979) and the American David K. Wyatt (1937–2006).

Distinguished for their depth of knowledge and ability to express it clearly and concisely, these were ideal instructors for young Ajarn Charnvit. Later colleagues mentioned in the dedication to Studies in Thai and Southeast Asian Histories include Yoneo Ishii (1929 – 2010), a Japanese historian of Thailand, and Benedict Richard O’Gorman Anderson (1936 –2015) a professor of International Studies, Government & Asian Studies at Cornell, whose 1983 book Imagined Communities redefined the origins of and motivations for nationalism. It is clear that these dedicatees were more than just intellectually formative for Ajarn Charnvit, but also good friends. In a moving speech available online from a ceremony in Surabaya last December in memory of Professor Anderson, Ajarn Charnvit stated:

To many of us in Southeast Asia and Siam, Ajarn Ben had been a good friend and a good teacher. He was kind, gentle, and always with provoking questions and comments of what he observed. He showed us how to see and understand our communities and our nations. He helped us to cross the limit and boundaries in our region, and not be กบในกะลา (kob nai kala) meaning our coconut shell. I met Ajarn Ben, the first time, in the fall of 1967, Ithaca, New York. He was young and impressive. As one of my Ph.D. thesis advisers, he helped me discovering not only my country, Siam, but also Indonesia, the Philippines, and many parts of Southeast Asia. He was a real inspiring scholar.

Noting that Professor Anderson, once forced into a prolonged exile from Indonesia, had visited Thailand shortly before his demise, Ajarn Charnvit added with typical precision:

Ajarn Ben said goodbye to us in Bangkok, his Southeast Asian base on 4 December 2015. We went to Burma and he went back to Java: land and peoples he probably loved the most. From here he went away, and his ash would be thrown into the Java Sea. Suharto cannot kick him out anymore. Goodbye Ben. You are well-loved and you have a good life and a good death.

Ajarn Charnvit’s capacity for emotional connection with people is evident not just in longtime friends, but even new acquaintances, as during a 2014 presentation in Chicago he won applause from a mostly female audience by alluding to the strength of women. He became especially aware of this forty years ago from the fortitude and courage of women in his own family during a turbulent time for the Kingdom. Generations of students have also been charmed by this emotional accessibility, and some recent ones have put online a tribute video, both serious and comic, to Ajarn Charnvit’s life and achievements. These students, like the general public, appreciate that Ajarn Charnvit’s open-mindednesss extends to what some historians would never risk, thinking about possibilities of what might happen in the future. Based on a firm grounding of knowledge about the past and present, these reflections are more than just speculations or predictions. They are signs of enduring hope, even within a context of apparent pessimism.

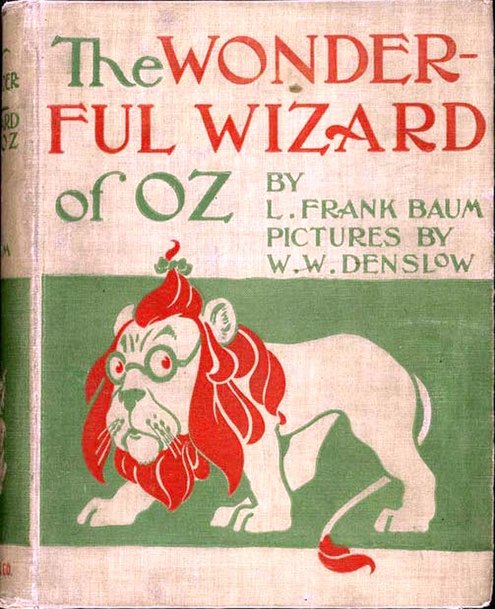

The introduction to Studies in Thai and Southeast Asian Histories is another indication of enduring faith that things will get better somehow, somewhere, and also that there is no place like home. It is entitled “Charnvit Kasetsiri’s Yellow Brick Road,” by another longtime friend, colleague, and scholarly collaborator, the historian Barbara Watson Andaya of the University of Hawaii, a classmate of Ajarn Charnvit’s at Cornell. The introduction focuses on one of his lesser-known achievements, his 1979 translation of L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz published in 2002 by Samnak Phim Dokya, directed by Narongsak Tantipinichwong, a former student of Ajarn Charnvit. L. Frank Baum’s book is rather more acerbic about illusions, delusions, and strange foreign lands than the sugary MGM musical film “The Wizard of Oz.” As Ajarn Charnvit has spent much of his scholarly career examining nations from inside and out, using different perspectives, he might also be intrigued by the fantasy novel The Wonderful Flight to the Mushroom Planet, written by the American author Eleanor Cameron in 1954, about children who visit the planet of Basidium, inhabited by little green people in a state of distress.

Helping people in distress is an underlying concern in Studies in Thai and Southeast Asian Histories, which contains many illuminating essays. Perhaps the most magisterial is a 2000 overview, “From ‘Siam’ to ‘Thailand,’” first published in Siam-Thai Millennia: Eventful Years in Thai History (2000). In this highly informative overview of how the name of Siam became Thailand, including lively pen portraits of the personalities involved in the change such as Pridi Banomyong, Ajarn Charnvit concludes:

‘Thailand’ would now seem to be firmly established as the name of the country, though who can state with any surety that the question of nomenclature will never be raised again.

Ajarn Charnvit himself raised it again more informally seven years later with a journalist from the The Star (Malaysia). He suggested that renaming the country might calm unrest in the South of the Kingdom:

Thailand means the land of the Thai (an ethnic group). That is a narrow definition as there are more than 40 ethnic groups in the country, including Thai (who make up 80% of the kingdom’s 65 million population), Chinese, Hmong, Akha, Karen, Laotians, Khmer and Mon,” explains the historian who is of Mon and Teochew blood. “The people in the south do not think that they are Thai. They consider themselves Malay or Pattani people. If we want our country to be more inclusive, the name Siam is more appropriate.

Asked if a name change would not confuse the farangs, Ajarn Charnvit replied with characteristic levity:

You’ve heard of Siamese cat or Siamese twins but you’ve never heard of a Thai cat. Thailand has been in use for 68 years, but Siam was used for thousands of years.

No less delightful is the conclusion of “Is ‘Thai Studies’ Still Possible?,” the keynote address at the 7th International Conference on Thai Studies: 4-8 July, 1999, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Discussing cultural mixes between nations, he mentions

a sort of potpourri, as you would say about a mixed salad, stew, or hot soup, a bit of this and that put together and becomes something edible.

Ajarn Charnvit goes on to cite a farang-Chinese-ish mix claiming to be Thai which he experienced in Singapore during a stopover from Bangkok to Amsterdam: an Amazing Burger Thai sold at the airport, which claimed that

The exotic taste of Thailand is now deliciously captured in McDonald’s new Amazing Burger Thai. A perfectly toasted muffin with juicy double chicken sausage, topped with authentic spicy Thai sauce.

In addition to a lively sense of humor, Studies in Thai and Southeast Asian Histories also leaves the reader with an ardent sense of shared human experience and deep respect for fellow human beings. “Zheng He – Sam Po Kong: History and Myth in Thailand” was presented in Beijing in 2005 on the 600th anniversary of Zheng He (1371–1433 or 1435), a Hui court eunuch, explorer, diplomat, and fleet admiral during China’s early Ming dynasty. Exploring local lore about this historical figure, who may or may not have travelled to Ayutthaya, Ajarn Charnvit made a field trip to Wat Phanan Choeng (called Sam Po Kong Temple). Such trips are frequent features of Ajarn Charnvit’s life with colleagues and students, but few are detailed in print as this one is in the 2005 presentation:

The temple is extremely popular among worshippers and tourists. It is rich, loud, well kept, colourfully and constantly renovated. People move around at all time, donating money, lighting up candles, and joss-sticks, paying homage to Buddha images and various Chinese deities. Chinese characters are seen almost everywhere. To my astonishment there is no statue of Zheng He…

After this vivacious depiction of the bustling life at a temple, Ajarn Charnvit, with the egalitarian approach of a sociologist, notes that he gained further data from a perhaps unexpected source:

Another interview was made with a Sino-Thai seller in front of the temple. The old man sells iced coffee and rice/pig leg; he seems to have more information.

Only a very great historian would be eager to gain information from a humble vendor of food and drink, not believing that knowledge and insight are only available from those with tenured jobs in universities.

(All images courtesy of fukuoka-prize.org; the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University; and Wikimedia Commons)