The Thammasat University Libraries have newly acquired the book, Asia’s Space Race: National Motivations, Regional Rivalries, and International Risks. Its author, Professor James Clay Moltz, works at the U.S. Department of National Security Affairs and in the Space Systems Academic Group at the Naval Postgraduate School. The TU Libraries own other books by Professor Moltz, including Crowded Orbits: Conflict and Cooperation in Space. Professor Moltz suggests that in general, European nations agree to cooperate in space research, but Asian countries tend to see the space race as a matter for individual competition:

Asia’s space powers are largely isolated from one another, do not share information, and display a tremendous divergence of perspectives regarding their space goals and a tendency to focus on national solutions to space challenges and policies of self-reliance rather than on … multilateral approaches.

While self-reliance in other spheres may be a virtue, in the field of space research, regional cooperation can have better results. Among the enthused readers of Asia’s Space Race was Bates Gill, director of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), who provided the following blurb:

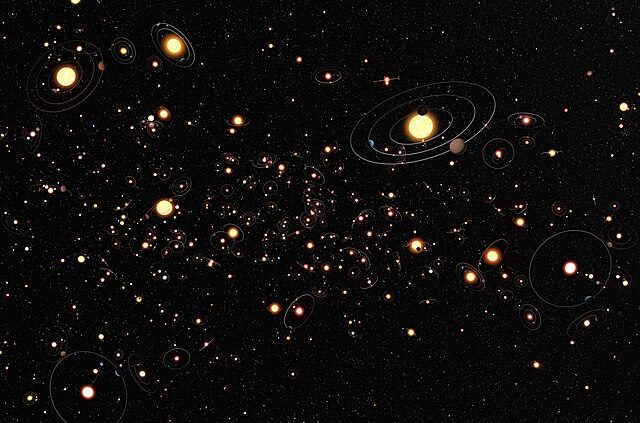

As humankind enters a new and more globalized spacefaring era, many hope outer space can become a commons for cooperation. Yet Asian space powers risk a more divisive and destabilizing prospect: an Asian space race. In this exceptional book, Clay Moltz provides the best read available to describe and explain the remarkably dynamic, increasingly crowded, and troublingly competitive field of Asian civil, commercial, and military space activity and presents a range of well-reasoned policy prescriptions for a stronger and more effective regime for space security among Asian powers and their neighbors, especially the United States.

In The Nonproliferation Review, the author Joan Johnson-Freese noted about Asia’s Space Race:

Today, space is a growth field in many Asian countries. Only three countries in the world have achieved human spaceflight; China was the third. It is also the third country to openly test an antisatellite weapon. China, Japan, and India all have robotic lunar programs. Japan has long had the technical capability to pursue space ambitions, but it lacked the political will, or, more accurately, the national political consensus needed to move forward. India’s space program was initially conceptualized in the 1960s as a purely civilian project, a utilitarian effort to aid domestic development; it unapologetically dismissed human spaceflight efforts and other flashy programs as luxuries pursued by richer countries. More recently, however, India has added human spaceflight and planetary exploration to its goals, announced plans for a military space command, and tested technology useful for an antisatellite capability based on missile defense technology.

Dr. Johnson-Freese notes that Professor Moltz continues to feel guarded optimism about the situation. Among the instances where Asia’s space development was a learning experience for all concerned was a 2007 Chinese anti-satellite test that made more people aware of the problem of debris in space, and the downsides of too much competition. He argues that if the United States and China work together more on space projects, both countries will benefit.

Last year in The Daily Beast, Professor Moltz observed:

The general public in the West largely views the exploration of space as dominated by the United States and perhaps Russia. Sometimes, as in the case of the Rosetta mission, they may give thought to Europe’s capabilities. Few people think of India when it comes to missions to Mars, but popular joy erupted across India in September 2014 after its Mangalyaan scientific spacecraft successfully achieved orbit around the red planet. One Indian reader responded to the story on a major online news outlet by posting: “It is [a] moment of pride as India becomes [the] 1st Asian nation to reach Mars.” And understood to all Indian readers was the point that China had—after a series of Asian firsts in space—finally been surpassed […] Vietnam is a surprising entry into Asia’s space community, but one with strategy in mind. Its distrust of its northern neighbor China has helped convince it to adopt an unlikely partnership with Japan, which has provided $1 billion of support toward construction of a national space center and the purchase of two Japanese Earth observation satellites, whose data may be shared by the two countries. Among others, Singapore has made major investments in satellite manufacturing, communications, and Earth observations, likely with the aim of bolstering its commercial independence and strengthening its military awareness of regional threats. Malaysia struck a deal with Russia to launch its first astronaut to the ISS in 2008, while investing in science education and satellite development. Indonesia, meanwhile, has plans for an equatorial launch complex, giving it easier access to fixed, geostationary orbital locations above the equator, which are ideal for communications satellites. While it is unlikely to fulfill its space ambitions soon, the fact that it has felt pressed to participate shows the strength of pressures in the region to enunciate a “space plan.”

Cooperation instead of conflict, as Foreign Affairs indicated in another review, would mean

bringing military applications to the fore instead of peaceful activities such as geographic sensing, weather forecasting, and telecommunications.

Thailand and Space

Happily, Thailand is active in peaceful and cooperative domains of space research. As The Nation reported last year, Thailand and China have

agreed to expand their 2013 agreement to cooperate in various fields of science and technology such as space technology, remote sensing satellites, solar energy and electric cars…the next stage will focus on the development of the Gistda satellite base in Chon Buri, which will play a key role in Thailand’s transition to a high-income, high-value economy. Gistda is a ground station for communicating with satellites and China is rapidly developing its satellite system, with plans to have sent 35 satellites in orbit by 2020. Its Beidou satellite navigational system is being developed as an alternative to America’s Global Positioning System, or GPS. In 2013, Thailand became the first foreign country to operate the system.

While one of the most obvious uses for such a system would be automobiles telling drivers which way they should turn to arrive at a destination, there are other important applications, especially involving weather and climate. This navigational system technology

can support energy conservation, efficient transportation, water management and disaster preparedness.

Scholarly Applications

A Thai ajarns have used careful readings of satellite images to draw conclusions about such matters as soil erosion. In Land Use Change Using Satellite Image and Digital Terrain Model Data, a research paper published last year in the Songklanakarin Journal of Science & Technology, Dr. Patchareeya Chaikaew of the Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Rajamangala University of Technology examined satellite images taken of Rattanakosinthe Khlong Kui watershed, Prachuap Khiri Khan Province, over a number of years. Soil erosion risk locations were predictable. Knowing what will happen to the earth in advance can be very useful and indeed life-saving information. Dr. Patchareeya concluded that while rice fields and rangelands increased, deciduous forests decreased, leaving areas at very high risk of soil erosion:

This study shows environmental problems such as deforestation and soil erosion in Thailand caused by human activities. The results of this study could support local governments, local residents, and farmers to focus on environmental problems in their regions. The erosion risk map can be used as the potential disaster information to establish field experiments plots for warning the risk area of soil erosion.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons).