A book newly acquired by the Thammasat University Libraries explains culture, customs and traditions of the Philippines. Authentic Though Not Exotic: Essays on Filipino Identity is a collection of essays analyzing the confrontation between Filipino and Western cultures. The book was donated to the TU Libraries through the generosity of Dr. Benedict Anderson and Ajarn Charnvit Kasetsiri, and it will be shelved in the Charnvit Kasetsiri Room of the Pridi Banomyong Library. Authentic Though Not Exotic takes into account Spanish influences as well as more recent discussion of Southeast Asian culture in the ASEAN community. It was written by Fernando Nakpil Zialcita, who earned a Ph.D. in Anthropology from the University of Hawaii. Dr. Zialcita is Professor Professor Emeritus at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the Loyola Schools, Ateneo de Manila University, where he headed the Cultural Heritage Studies Program. Born in Manila, Dr. Zialcita did extensive field research in farming communites in the Ilocos, a region in the Philippines, encompassing the northwestern coast of Luzon island. It is known for its historic sites, beaches and the well-preserved Spanish colonial city of Vigan. Dr. Zialcita is also noted as an expert in urban heritage and regeneration, advocating the preservation of built heritage as project director of a project preserving and protecting Philippine heritage architecture. Alert to both the Hispanic and Southeast Asian worlds, Dr. Zialcita examines such fields of study as traditional architecture, cookery and popular Christianity. He points out that as a recent construct, the concept of Southeast Asian culture should be reexamined to show the true diversity it contains. Preserving and Protecting Philippine Architectural Heritage, a project completed in 2011, compiled an online database outstanding architectural achievements of Philippine society, as a resource for researchers, and to facilitate preservation. Projects and models of heritage preservation in other countries related to conditions in the Philippines were also studied. Cultural heritage among local governments was raised, as well as public awareness, through newly published guides to historic and Metro Manila. Exhibits of architectural heritage in public spaces were further features of consciousness raising. In an earlier project from 2004, Dr. Zialcita headed More than a Thoroughfare: The Uses and Interpretations of a City Street. This ethnographic study repertoried how street activities were interpreted, according to the social level of each individual participant and observer. Examining how people react to events in a specific place, depending on their roles in society, this was an effort to explain why people interact the way they do. More recently, in 2015 Dr. Zialcita completed a special project at the Ateneo de Manila University, Building Pride of Place through the Ateneo Cultural Laboratory.

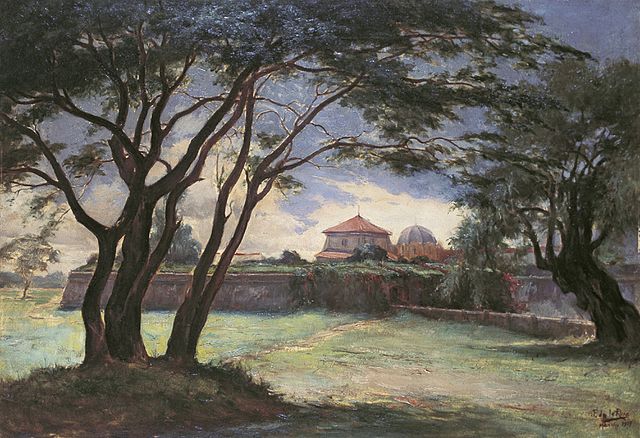

Bohol, the Philippines.

Among the many national sites compared and contrasted by Dr. Zialcita is Bohol, a province of the Philippines comprising Bohol Island and numerous smaller surrounding islands. Bohol is known for coral reefs and geological formations such as the Chocolate Hills. They are known as the Chocolate Hills because during the dry season, they turn the color of cocoa, unlike the surrounding green color of the jungle. In addition to such natural wonders, Bohol also has Spanish churches and houses dating back to the 1800s. In his book Philippine Ancestral Houses, 1810-1930, Dr. Zialcita concentrates on buildings. Yet other aspects of popular culture also intrigue him. For example, Asin Tibook, an artisanal salt manufactured in Alburquerque, Bohol. As reported in The Philippine Star in 2012:

Asin Tibook, introduced to me by Dr. Fernando Zialcita of Ateneo de Manila University’s Department of Sociology and Anthropology, is an indigenous way of extracting salt from our abundant seawaters. It is also a dying craft. Making Asin Tibook is tedious. Coconut husks are soaked in saltwater for three months before they are dried out in the sun and slowly burned over three to four days to produce a fine ash. Filtration systems made of buri and the ash are used to filter seawater. The brine that is collected is then poured into small clay pots that are cooked over an open flame for nine hours. These are then left to cool overnight, resulting in neat little clay-pot packages meant to be dramatically cracked open to reveal clumps of fine, earthy and smoky sea salt. Though it doesn’t have the crunch of Fleur de Sel, it definitely packs more punch and depth. The crystals gently and delicately melt in the mouth, the flavor is unique and the idea is romantic. A fantastic product that could hold its own in Zabar’s or Le Bon Marché; an idyllic double-entendre — salt is often used to preserve food but in this case it can also preserve our cultural heritage.

That year, Dr. Zialcita presented a salt-tasting event at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology (DSA) and the Institute of Philippine Culture (IPC). Dr. Zialcita is quoted in the article:

Filipinos are too apologetic about their own culture vis-a-vis some foreigners who have a preconceived notion of Asia … being uneasy about not being Asian enough. So what if we’re not exotic enough?

To promote regional cooking and products, collaboration among anthropologists, chefs and food historians was suggested as light meal of salted and unsalted dishes was tasted, to better appreciate what Asin Tibook adds to the culinary arts. These and other events sparked enthusiasm from students, including one who posted online a response to Culture and the Senses, a class taught in 2008 by Dr. Zialcita or Doc Z as the students informally refer to him. The student praised the class because

- It uses your five senses – sight, smell, taste, hearing and feeling – to evaluate the world around you.

- It juxtaposes Filipino culture with European, American and Asian Cultures.

- I saw many different opportunities for business and national development through cultural industries.

In comparing and contrasting ethnic and social customs, Dr. Zialcita underlines that diversity is the key, and it is pointless to debate which cultural habit is more authentic than another. In Why insist on an Asian Flavor?, a research article printed in Philippine Studies in the year 2000, Dr. Zialcita offers some appetizing details to prove his points:

Javanese dip fried and roasted foods either in sambal, a paste made from red chili peppers, garlic, salt and sugar, or in terasi, a fermented shrimp/fish paste that may be studded with chopped red chilies. Tagalog prefer dipping sauces with a sour base: palm vinegar with a lone crushed chili pepper pod; vinegar with slivers of onion with mashed garlic and pepper; chopped green camias and tomatoes; or small raw pickled mangoes mixed with tomatoes and coriander. Though the Javanese use some tamarind juice in their dishes, they complain that the Tagalog’s sour dishes, especially those cooked in vinegar, upset their system. On the other hand while the Tagalogs use some chili pepper, many of them claim that sambal bums their stomach. Which taste is more authentically “Asian”: the Javanese or the Tagalog?… For their dipping sauce, North Vietnamese favor nuoc mum-which like our patis is an amber-colored fish sauce. On this they sprinkle a few slices of chili. Cantonese food, which has influenced Filipino sensibility, uses ginger, pepper and soy sauce but not the variety of spices one finds in Java, certainly not the chili pepper that Szechwanese love. While Koreans love plenty of chilis and garlic, Japanese abhor their taste and their smell as low class. They prefer mustard (wasabi) and soy sauce. Who is more Asian: the Japanese who hate garlic and chili or the Szechwanese and Koreans who love these?

Dr. Zialcita concludes that assuming that an identifiable pan-Asian sensibility exists may not be the best approach to comparative cultural studies in the ASEAN community.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)