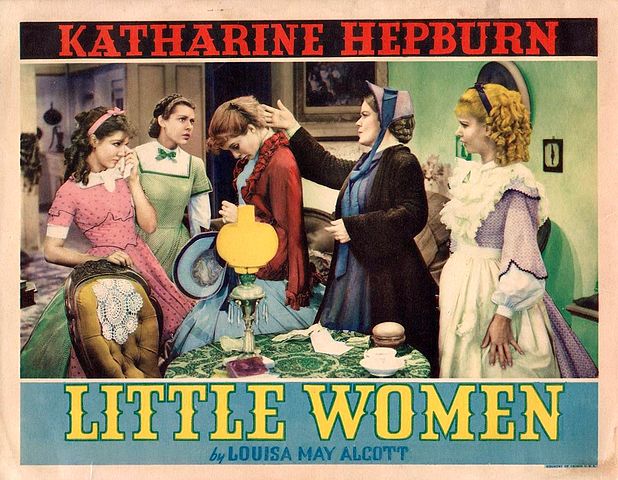

Little Women is a novel by American author Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888). It was published in two volumes in 1868 and 1869. The novel tells the story of how four sisters – Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy March – grow up. Little Women is set in Concord, Massachusetts, in New England, USA. The story tells of the importance of home life, work, and love. The Thammasat University Library owns different editions of Little Women, including a sound recording of a shortened version of the book, as well as books about the life and work of Louisa May Alcott. There have been many film and television adaptations of Little Women. Last year, a BBC television historical drama version starred Emily Watson, Michael Gambon and Angela Lansbury. In 1987, a Japanese anime series was produced by Nippon Animation, Tales of Little Women, or Love’s Tale of Young Grass. In 1993, this popular series had a sequel, Little Women II: Jo’s Boys. In the anime, as in the novel, the family deals with the dangers and worries of the American Civil War, as the head of the family, Mr. March, is fighting with the Union Army to free the slaves in America. In real life, Louisa May Alcott campaigned energetically to free all slaves. There have also been adaptations of Little Women as a Broadway musical and opera. Clearly a lot of people continue to enjoy this story, even when few readers are still interested in most American novels published in the 1860s. Part of the reason is that Louisa May Alcott’s publisher urged her to write a story for girl readers. She did so, but made the novel interesting for all sorts of readers. Literary critics today disagree about the meaning of the title Little Women. Some think it refers to the fact that the March sisters are young women, just out of childhood. Others feel it is a reference to how in American society of the 1800s, women were considered to be of smaller importance than men. They were not seen as important, so they were described with the adjective little. One sister, Meg, teaches four children of a family who live nearby. Another, Jo, is a home help aid for her grand-aunt March, a rich old widow. The third sister, Beth, does housework at home, and the youngest, Amy, spends much time with her lessons and homework. They interact with their neighbors, face the dangers of disease, and have other challenges. They also start to think about love and marriage. The plain and direct style of Louisa May Alcott’s writing strikes a realistic note, for example from Chapter One:

“Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents,” grumbled Jo, lying on the rug.

“It’s so dreadful to be poor!” sighed Meg, looking down at her old dress.

“I don’t think it’s fair for some girls to have plenty of pretty things, and other girls nothing at all,” added little Amy, with an injured sniff.

“We’ve got Father and Mother, and each other,” said Beth contentedly from her corner.

The four young faces on which the firelight shone brightened at the cheerful words, but darkened again as Jo said sadly, “We haven’t got Father, and shall not have him for a long time.” She didn’t say “perhaps never,” but each silently added it, thinking of Father far away, where the fighting was.

Some book reviewers of the time appreciated how realistic the characters’ speech and behavior was. They seemed like real human beings. Sometimes Louisa May Alcott added amusing observations about how men do not like to take advice from women. When they do take advice from women, they only admit it if the advice is no good:

When women are the advisers, the lords of creation don’t take the advice till they have persuaded themselves that it is just what they intended to do. Then they act upon it, and, if it succeeds, they give the weaker vessel half the credit of it. If it fails, they generously give her the whole.

In other books, Louisa May Alcott wrote about how women were unfairly limited to taking care of the home in her era. She believed strongly that it was just as important for girls to do something useful with their lives in the world as it was for boys. This educational approach made an impression on her many readers. Part of the ambitious program in Little Women was inspired by the fact that Louisa May Alcott grew up in a literary household, Her parents were friends with many of the most famous writers of New England, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau. The TU Library has books by and about all of these important writers and thinkers. Although Louisa May Alcott’s family was very intelligent, they were also poor, and sometimes went hungry. She learned at a young age that it was necessary to work in order to live. In addition to writing a great deal, she also worked as a teacher, governess, domestic helper, and she did sewing as well. In the 1840s, her parents, who were opposed to slavery, helped to hide a runaway slave in their family home for a week. Louisa May Alcott also believed deeply in women’s rights, including the right to vote. At an especially difficult moment of her life, she was inspired by reading the novelist Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography of Charlotte Brontë. She found many similarities between the life of the British novelist Charlotte Brontë and herself. Since the TU Library owns a copy of Gaskell’s life of Charlotte Brontë, students and ajarns can appreciate this book and compare it to the challenges in the life of Alcott. Before writing Little Women, Louisa May Alcott enlisted to serve as a nurse during the Civil War. In 1862 and 1863, she served as a nurse at a hospital in Washington, D. C. for some weeks before falling ill with typhoid fever, a dangerous ailment. One of her most appreciated books apart from Little Women is drawn from her experience with health care. Hospital Sketches (1863) discusses how hospitals of her time were badly managed, and how surgeons at the time were not caring or sensitive about the sufferings of patients.

Siam and Little Women

In one of her later books, Alcott shows how children in New England homes in the 1880s were aware of Siam. Jack and Jill: A Village Story was published in 1880. In a small New England town after the Civil War, two young friends, Jack and Janey – known as Jill – recover from a sledding accident. One of their friends, Molly, plays imaginary games with her baby brother Boo about world travel, involving a family servant who takes care of them, Miss Bathsheba Dawes, known as Miss Bat. In the American girl’s imagination, her room in the family home is Siam, and since the room is messy, it needs to be cleaned up:

“I’ll play it is Siam, and this the house of a native, and I’m come to show the folks how to live nicely. Miss Bat won’t know what to make of it, and I can’t tell her, so I shall get some fun out of it, any way,” thought Molly, as she surveyed the dining-room the day her mission began. The prospect was not cheering; and, if the natives of Siam live in such confusion, it is high time they were attended to… “My patience! how the Siamese do leave their things round,” she exclaimed, as she surveyed her room after making up the fire and polishing off Boo. “I’ll put things in order, and then mend up my rags, if I can find my thimble. Now, let me see;” and she went to exploring her closet, bureau, and table, finding such disorder everywhere that her courage nearly gave out… I feel like a Siamese twin without his mate now you are gone, but I’m under orders for a while, and mean to do my best. Guess it won’t be lost time.”

Naturally, Americans in the 1800s were informed about Siam because of the famous conjoined twins, Chang and Eng Bunker, who lived there. American children also had many illustrated books and magazines showing faraway locations such as Siam. The active international communication of HM Rama IV (King Mongkut), also meant that Americans, including children, were aware of Siam in the 1800s.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)