Cognitive bias II

The student may also ask us:

Do I have to be aware of all these cognitive biases to avoid making mistakes in my thesis or academic research project?

We would say:

No, but it helps to remember to have an open mind, and if we react in some ways to our results or findings, we may be responding to our previous experience more than to what the new data really means.

The student may then inquire:

What are some other examples of cognitive biases?

We may reply:

Gambler’s fallacy suggests that what has happened in the past will somehow change what will happen in the future, when this is not true. Fallacy is a noun meaning a mistaken belief or error in reasoning or argument. The word fallacy derives from a Latin term meaning to be deceived.

A common example of gambler’s fallacy has to do with the fact that when we toss a coin to see if it will land on heads or tails, the chances of either result remain at 50/50 percent, regardless of how many times we flip the coin. However, some people feel that because they have flipped the coin and heads or tails appeared a few times in a row, the odds have changed for the next result. This incorrect interpretation is a form of gambler’s fallacy. Likewise, for researchers repeating the same experiment, just because one result has appeared repeatedly, this should not change the likelihood of receiving the same or different results in future. This is why it is especially important to keep an open mind about results and findings. Other cognitive biases:

Groupthink: when people want to agree and think the same way, they arrive at interpretations that no longer have much to do with accuracy or objective truth.

Illusion of control: When we think we have a lot of influence over events or results, but we really do not, this can affect our interpretation of research findings.

Illusory correlation: If two things happen, we may mistakenly think thay they have something to do with one another, or are somehow interconnected. In fact, there may be no relation between the two events, except what we wish might occur. In this case, our imaginations have tried to add to the reality of data, to find an interpretation that is not based on fact. We have elaborated on the basic findings, and the results may no longer be strictly accurate.

Illusory truth effect: If something is easy to understand, or has often been said, we tend to think it may be true, even if the data is against it.

Mere exposure effect: If researchers are familiar with something, they tend to prefer it to other things that may be less known or unusual. As a result, we may not appreciate new discoveries for their full value. It is a human tendency to feel more comfortable with what is usual and recognizable, and to be more hesitant with what is not.

Negativity bias: According to psychologists, people tend to have more detailed memories of painful past experiences than more pleasant ones. If we stress what is negative in our research findings, we may be offering an interpretation that is not objective.

Normalcy bias: Researchers tend to prefer to stick to what has already happened, so if something totally new or unexpected occurs, it can be difficult to react to it, or plan for it in the future.

Optimism bias: Researchers tend to want good results, and prefer them to bad or negative findings. So we may make the mistake of trying to identify good results when what we really have is something more negative, or that does not satisfy our expectations. This type of wishful thinking can keep us away from an objective interpretation of findings.

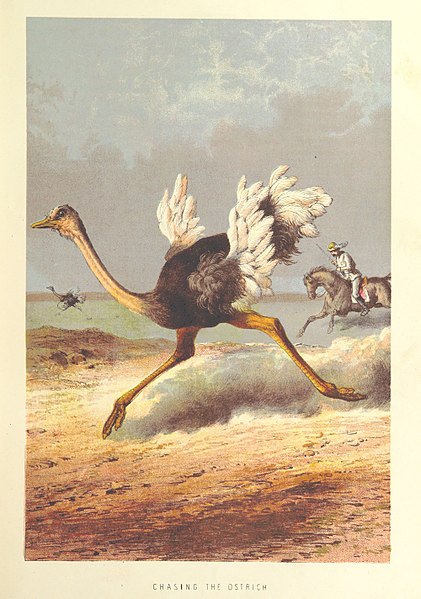

Ostrich effect: Sometimes when researchers receive a clearly negative result or finding, they prefer to ignore or overlook it. This is called the ostrich effect, because of the popular misunderstanding that ostriches bury their heads in the sand to avoid seeing something unpleasant. As TU students of biology know, ostriches do not really bury their heads in the sand to avoid seeing things. They dig holes in the sand to make nests for their eggs, which they turn over repeatedly during the way. So to uninformed observers, they may seem to be burying their heads in the sand. In fact, they are just being careful parents.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)