Thammasat University students interested in history, sociology, psychology, psychiatry, gender studies, political science, folklore, the arts, and related fields, should find a new acquisition by the TU Library to be useful. The Monster Theory Reader edited by Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock discusses such subjects as monster culture, the uncanny, Sigmund Freud, fantastic biologies, structures of horrific imagery, gothic monstrosity, monstrous races, the undead, religion and monsters, invisible monsters, zombies, and ecocriticism.

The book is shelved in the General Stacks of the Pridi Banomyong Library, Tha Prachan campus.

The Thammasat Library collection includes a number of other books on different aspects of monsters.

As TU students know, a monster is considered a type of grotesque creature, whose appearance frightens and whose powers of destruction threaten the world’s social or moral order.

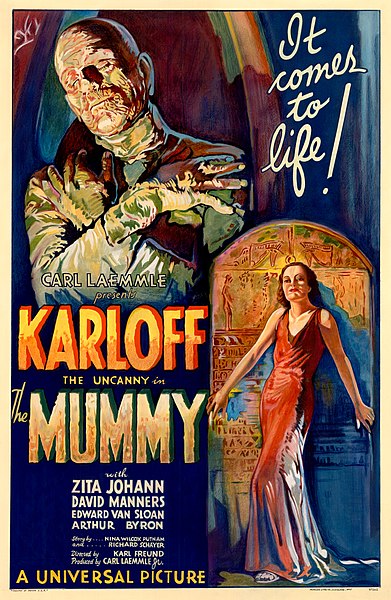

Monsters have appeared in literature and in feature-length films. Well-known monsters in fiction include Count Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster, werewolves, mummies, and zombies.

The word monster derives from a Latin term meaning to remind or warn. So a monster is a warning in the form of something strange or unusual, through which the gods point out potential bad things.

TU students in the social sciences may note that monster theory is an increasingly popular field for academic research.

As one specialist observed in an article posted online in 2015 by Science X, is a leading web-based science, research and technology news service:

One of the things monster theory tries to get at is why humans throughout history are fascinated with this figure of the monster, and Halloween is a reminder of that…There’s no simple answer for why we’d be fascinated by these things. It gets at a lot of our anxieties about our own mortality, sadness about the losses we experience and fears of what’s to come. But it’s also about desire. One of the things that frighten us about the monster is our strong identification with it: what it can do, the way it can violate social norms. It can live forever. It can destroy things… Zombies are the ascendant monster of the last few years…The zombie is the most mindless of monsters. They exist really just to be killed off, and there’s no possibility of any connection with them. I think part of it is that we do want a monster we can just destroy without tough moral questions or qualms of conscience.

Thai research in monster theory

An example of academic research in the Kingdom that focuses on monster theory is Monsters in contemporary Thai horror film: image, representation and meaning, a Ph.D. thesis in Thai studies by Ji Eun Lee at the Chulalongkorn University Faculty of Arts in 2010. Its subject was monsters in Thai motion pictures. The abstract reads as follows:

The purpose of this study was to illustrate how the images of monsters are projected in Thai horror film and to examine the metaphorical meaning and representations of monsters. The scope of my research was Thai horror films released on the screen from 1999 to 2008, with selected films specifically elaborated with regard to Thai cultural, social, and political contexts. This study defined the characteristics of Thai horror films, explaining that hybridity with other genres, such as comedy and romance, and sexuality are important components, while Buddhism and supernaturalism are crucial elements of the films. In particular, the Thai Buddhist belief of ‘cause and effect’ and ‘karma’ predominates over all Thai horror films. Ghosts are the primary horror object in Thai horror film, especially female ghosts, who appear with supernatural power to avenge or fulfill their grudge in the traditional Thai ghost films. However, human monsters using black magic, again mostly female, appear more often in the later 2000s, and pursued their desires in more forceful and active ways. In addition, men, children, and the aged also appear as monsters in Thai horror films, and they represent as the ‘Otherness’ of Thai society. Interestingly, monsters in contemporary Thai horror films are not only evil, but can also be good, since they can be society’s ‘guardian of morality and mores’ from the bad or even ‘loss of locality or tradition’. Horror film usually implies social, political or cultural problems and issues, and also deals with collective fear and anxiety. In this study, 11 films with four issues were investigated: 1) trauma from the IMF crisis and unsettled social climate is reflected in Nang Nak (1999), Phi Sam Baht (2001), and Rongraem Phi (2002); 2) fear for natural calamities and pandemic disease is portrayed in Khun Krabi Phi Rabat (2004) and Takhian (2003); 3) women’s issues and men’s anxiety for their loss are represented in Buppha Ratri (2003), Ban Phi Sing (2007) and Long Khong 1 and 2 (2005, 2008); and 4) political turmoil is implied in Faet (2007) and Ban Phi Poeb (2008).

One of the favorite subjects for monster theory researchers is the precedent set by In and Chun (1811-1874), conjoined twins born in 1811 in the Mae Klong Valley, Samut Songkhram Province, Siam, during the reign of HM King Rama II.

Their father, Ti-aye, a fisherman, was of Chinese origin and their mother, Nok, possibly of Chinese-Malay background, so the boys were known as the Chinese twins in their homeland. Joined at the sternum by a piece of cartilage, the boys were athletic and enjoyed playing badminton and performing tumbling tricks despite their disability. This caught the eye of a traveling British merchant who exported them to America to exhibit them in sideshows.

Renamed Chang and Eng, they would later convert to Christianity and adopt the family name Bunker, as they settled down in North Carolina. They both married and had several children, some of whom fought for the Confederacy in the American Civil War. They became so famous as performers that a new term, Siamese twins, was used until fairly recently to describe conjoined twins.

Considered as monsters, they were widely famous across America of the 1850s, and considered to possess substantial symbolic potential. Here are some thoughts about monsters and monster theory:

As a survival mechanism, fear can help us avoid dangerous situations or prepare us for hostile confrontations. But being scared all the time isn’t healthy. It can lead to panic or emotional breakdowns. So why in the world would we even want to have monsters as part of our popular entertainment? Why read (or write) stories about monsters if we know it will ultimately make us unnecessarily experience an emotion that isn’t pleasant? To come back to Godzilla, why would the Japanese want to be reminded of the horror of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Well, to answer those questions, let’s consider the ancient Greek concept of Catharsis.

- Stan Lee’s How To Draw Superheroes, by Stan Lee

Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.

- Friedrich Nietzsche

Is it better to out-monster the monster or to be quietly devoured?

- Friedrich Nietzsche

Battle not with monsters, for then you become one.

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

There are very few monsters who warrant the fear we have of them.

- André Gide

Adversity makes men, and prosperity makes monsters.

- Victor Hugo

Calling someone a monster does not make him more guilty; it makes him less so by classing him with beasts and devils.

- Mary McCarthy

One of the many reasons for the bewildering and tragic character of human existence is the fact that social organization is at once necessary and fatal. Men are forever creating such organizations for their own convenience and forever finding themselves the victims of their home-made monsters.

- Aldous Huxley

(all images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)