Thammasat University students are cordially invited to participate in a free online lecture from Oxford University on John Stuart Mill and the East India Company.

The Thammasat University Library collection includes several books by and about the English philosopher and political economist John Stuart Mill.

John Stuart Mill, who lived in the 1800s, was a highly influential thinker in such fields as He saw liberty as justifying freedom of the individual as opposed to unlimited state and social control.

The lecture will take place on Thursday, 6 May 2021 at 8pm Bangkok time.

Participants can log in with Microsoft Teams.

The speaker will be Mr. Andrew Dalkin, a doctoral candidate at the Faculty of History, New College, Oxford.

TU students interested in attending should write to the following email address:

Since John Stuart Mill did not worship at the Church of England, he could not attend Oxford or Cambridge Universities.

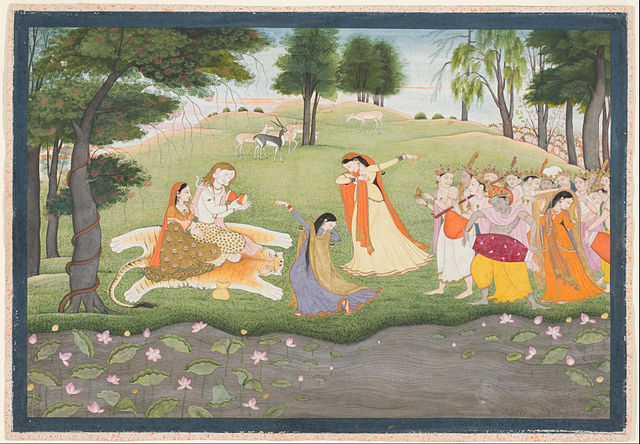

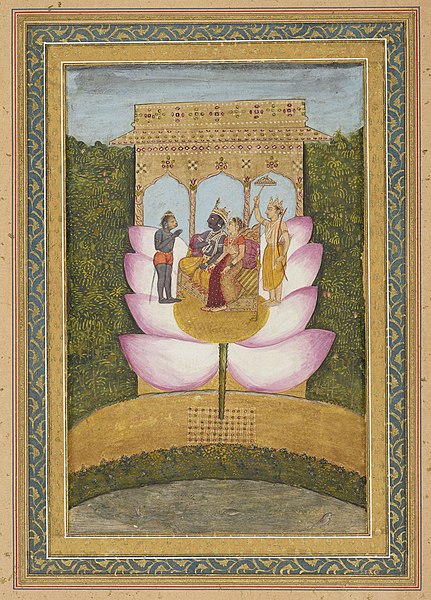

Instead, like his father, he went to work for the East India Company, which was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, at first with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia), and later with Qing China. The company seized control of large parts of the Indian subcontinent, colonized parts of Southeast Asia and Hong Kong after the First Opium War, and maintained trading posts and colonies in the Persian Gulf Residencies.

Mill worked as a colonial administrator at the East India Company lasted for 35 years, starting when he was seventeen years old and only ending when the company was abolished.

Like his father, James Mill, who wrote a history of British India, John Stuart Mill was well aware of the damage done by colonialism.

The East India Company took over other countries through conquest, treaty, and annexation.

And yet, he also developed influential ideals about civil and political freedom.

How did his ideas freedom coexist as a practical matter with colonialism?

Mill believed that people could be brought to accept the truth through calm logic.

His father wrote that nations of the East, such as China and India had once been progressive but lost this advantage by losing originality and a sense of liberty.

Mill felt that the East India Company would help this situation by promoting ideals of good government.

Here are some quotes about Mill by authors, many of whom are represented in the TU Library collection:

- Mill’s great merit was the defence of the minority, [and of the rights of minorities].

Lord Acton, private notes, quoted in G. E. Fasnacht, Acton’s Political Philosophy: An Analysis (1952)

- [Mill] was himself fresh and delicate and pure; but that is the business of a flower. Though he had to preach a hard rationalism in religion, a hard competition in economics, a hard egoism in ethics, his own soul had all that silvery sensitiveness that can be seen in his fine portrait by Watts. He boasted none of that brutal optimism with which his friends and followers of the Manchester School expounded their cheery negations. There was about Mill even a sort of embarrassment; he exhibited all the wheels of his iron universe rather reluctantly, like a gentleman in trade showing ladies over his factory. There shone in him a beautiful reverence for women, which is all the more touching because, in his department, as it were, he could only offer them so dry a gift as the Victorian Parliamentary Franchise.

G.K. Chesterton, The Victorian Age in Literature

- I went to Cambridge in the middle [eighteen] sixties. … Mill possessed at that time an authority in the English Universities…comparable to that wielded forty years earlier by Hegel in Germany and in the Middle Ages by Aristotle.

Arthur Balfour, Theism and Humanism: Being the Gifford Lectures Delivered at the University of Glasgow, 1914

- I never knew a finer, tenderer, more sensitive or modest soul among the sons of men. There never was a more generous creature than he, nor a more modest.

Thomas Carlyle’s reaction to Mill’s death, quoted in Letters of Charles Eliot Norton, Volume I (1913)

- John Stuart Mill was the saint of rationalism for a good reason. Mill’s ideas are the roots of the self-destructive character of a rationalist or constructivistic view of how civilization could be organized. Since Mill, this muddle about facts has guided policy and most of the strivings of people of good will, who were inspired by a false picture, based on a worldwide division of labor, of how a society worked. It was from Mill’s muddle (and the similar deceptions of Marx) and from the confusion of those pretended defenders of liberty who proclaimed a new moral postulate which required a complete suppression of individual freedom that the whole muddle of the middle derived. The ideal of freedom was increasingly relegated to second place by the idea of social justice. However, the two are incompatible. If one accepts the principle of social justice, one cannot preserve the market economy which provides that which social justice would like to distribute. The two principles are antagonistic and irreconcilable. There can be no halfway house between them. As the promise of social justice cannot be generally satisfied and also cannot be refused to all others once it has been conceded to some, there can be no question about where one’s choice must be if one really wants to help the poor.

Friedrich Hayek, “The Muddle of the Middle”, in S. Pejovich (ed.) Philosophical and Economic Foundations of Capitalism (1983)

- Without a thorough study of Mill it is impossible to understand the events of the last two generations, for Mill is the great advocate of socialism. All the arguments that could be advanced in favor of socialism are elaborated by him with loving care. In comparison with Mill all other socialist writers—even Marx, Engels, and Lassalle—are scarcely of any importance.

Ludwig von Mises, Liberalism (1927)

- He was a friend of my parents, and I didn’t know him through that because my parents died when I was quite tiny; but nevertheless it made me know he existed, and so I read his books. And, well, they were the sort of books that would appeal to me. They were empiricist and liberal and humane. And I liked him very much.

Bertrand Russell, in an interview (10 June 1962)

- Mill’s Autobiography is a brilliant dissection of Victorianism’s mid-life crisis. It raised two problems which are vital for understanding the Cambridge civilisation of Keynes’s day. First, how is one to reconcile the claims of personal happiness and social duty when the two diverge? And is happiness or pleasure an adequate aim for human conduct? Are there not some things worth doing some dispositions worth cultivating, which are valuable in themselves, irrespective of any Utilitarian justifications they might have? Is it not better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied?

Robert Skidelsky, John Maynard Keynes: 1883-1946: Economist, Philosopher, Statesman (2003)

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)