![]()

Thammasat University students are cordially invited to participate in a free virtual conference presented on Saturday, 29 May and Sunday, 30 May as a student-led postgraduate colloquium organized by the College of Arts and Law, University of Birmingham, the United Kingdom.

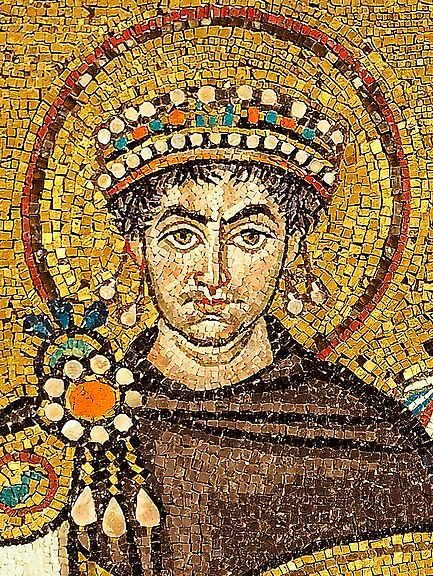

The 21st Annual Postgraduate Colloquium of the Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies will have as its overall theme: Color, Emotion and Senses.

29th-30th May 2021, Virtual Conference (Via Zoom)

Students may register at this link:

https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/cbomgs-21st-annual-postgraduate-colloquium-tickets-151458553611

The Thammasat University Library collection includes many books about different aspects of the Byzantine empire.

Among presentations will be a lecture on Musical Instruments and Dance in Byzantium by Dr. Antonios Botonakis of Koç University, a non-profit private university in Istanbul, Turkey and The impact of iconoclasm in Byzantine arts and social life by Dr. Charalampos Trasanidis of the University of Thessaloniki, Greece and Dr. Eleni Aitsidou of the University of Epirus, Greece.

As students of the Department of History, Faculty of Liberal Arts, Thammasat University know, The Byzantine Empire was an influential civilization that began over 2300 years ago when a Roman emperor dedicated a New Rome on the site of the ancient Greek colony of Byzantium. Though the western half of the Roman Empire fell just over 1500 years ago, in the East it survived for another millenium, resulting in a tradition of art, literature and education.

The Byzantine Empire finally fell over 500 years ago, after an Ottoman army stormed Constantinople.

The term Byzantine derives from Byzantium, an ancient Greek colony founded by a man named Byzas.

Byzantium served as a transit and trade point between Europe and Asia.

The Byzantine Empire was the only organized state west of China to survive without interruption from ancient times until the beginning of the modern age.

Byzantine culture would have a great influence on the Western intellectual tradition, as scholars of the Italian Renaissance sought help from Byzantine scholars for translating Greek and Christian writings.

Long after its fall, Byzantine culture and civilization continued to exercise an influence on countries that practiced the Eastern Orthodox religion, including Russia, Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia and Greece.

Thailand and Byzantium

TU students may consider that the Byzantine Empire seems far from the Kingdom, however academic researchers in Thailand have discussed an early Byzantine lamp that was brought as far as Siam some centuries ago.

This large and elaborate bronze lamp is 26.7 cm high × 29.5 cm long.

Its pieces were cast separately, then soldered together. It was filled with oil through a hinged circular lid at the top of the body.

The lid is decorated with the face of a Silenus, an associate of the wine god Bacchus in Roman mythology or Dionysos in Greek mythology. Projecting from the back of the lamp is a stylized handle supported by two dolphins.

Dolphins appear frequently in early Byzantine lamps. They were associated with the classical god of wine, Bacchus or Dionysos, who was kidnapped by pirates whom he then transformed into dolphins.

More generally, leaping dolphins were equated with leaping flames.

This lamp probably arrived in Siam through long-distance trade routes. It may have been made in Egypt, from which it traveled through the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean and then to Siam.

An article from 2008 in The Journal of the Siam Society by Professor Brigitte Borell of the University of Heidelberg, Germany, discusses the early Byzantine lamp from Pong Tuk:

It belongs to a class of bronze lamps common in the Eastern Mediterranean area in this period. In addition, it is compared to some very similar lamps forming a closely related group; the lamps of this group might have been manufactured in Byzantine Egypt. The archaeological importance of the Pong Tuk lamp lies in the fact that an Eastern Mediterranean artefact of the fifth or probably sixth century CE has been found in Thailand. It has to be seen in the context of long-distance trade in that period via the Red Sea to India and beyond which is described in great detail in a written Western source of the sixth century CE. The lamp was found at Pong Tuk in Central Thailand, about 30 km west of Nakhon Pathom, at the site of a Buddhist architectural complex of the Dvaravati period. It was found in two parts by local inhabitants in 1927, and shown to G. Coedès on his first visit of the site on 2 August. He recognized it immediately as a Roman lamp and referred to it in the following year in his report on the excavations at Pong Tuk as an imported Roman lamp of the first or second centuries CE. Since then, the lamp has attracted a lot of attention and has been quoted as evidence of early Mediterranean imports into Southeast Asia in many publications. Interest in the lamp increased when in 1955 the classical archaeologist C. Picard published an article suggesting an even earlier date for the lamp… In February 2007, the opportunity was given to me to study the lamp in detail in the Bangkok National Museum and to take photographs.

As Professor Borell noted, the lamp is

complete and very well preserved, except for a hole on the left side of the body. The patina is dark blackish-green with patches of the exposed yellowish metal surface. The lamp is cast in separate pieces, assembled by soldering: body, handle, and plate with a sleeve for the socket underneath and inside the body. The circular lid over the filling hole is fastened with a hinge-pin. When found, the handle and body were apart, and their present assembly is modern. The body of the lamp is pear-shaped with a long flaring nozzle ending in a circular dished area with a small round opening for the wick. The horizontal edge of the saucer-shaped dished area is decorated with three molded concentric rings. The body of the lamp is plain and rests on a high flaring base. The upper part of the base is slightly receding and decorated with four faint grooves. The flaring lower part of the base is plain on the outside but has on the inner side a few concentric grooves. On the underside of the lamp, flush within the base, is an inserted circular plate with a square socket, a device for placing the lamp on the tetragonal spike of a lampstand; the tapering sleeve of the socket extends within the oil-chamber of the lamp. On top of the body is the large circular filling hole, into which the oil was poured; it is not directly above the base but set further back towards the rear. The filling hole has a raised rim and is covered with a circular lid operated on a hinge at the rear. The lid still swivels freely. Its convex upper side is decorated in relief with a head en face of a Silenus, one of the followers of Dionysos, the Greek god of wine.

So far, no analysis has been carried out, so the precise composition of the metal is not known.

An earlier article from 1989 also concurred that the Pong Tuk Lamp is of early Byzantine origin.

Its presence in Siam over 1500 years ago is reasonable considering Southeast Asian trading patterns with the West and local interest in exotic goods…the number of Western-made objects found in Southeast Asia is very small, making the Pong Tuk lamp, whenever it was imported, highly unusual.

Historians speculate that the lamp may have been brought by Western traders and presented as an offering at a Buddhist temple in Siam.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)