The Thammasat University Library has newly acquired a book that should be useful for students who are interested in literature, mythology, comparative religion, and gender studies.

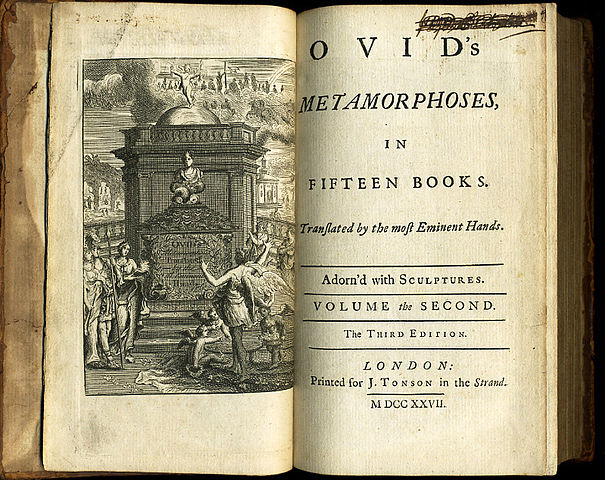

Metamorphoses was written by Ovid, a Roman poet who lived over 2000 years ago.

Ovid is generally considered one of the one of the leading poets of Latin literature, along with Virgil and Horace.

The TU Library collection also includes a number of other books by and about Ovid.

Although Ovid was a popular writer, he was exiled by the emperor Augustus to a remote province, which he claimed was because of a “poem and a mistake.”

Ovid is best remembered for the Metamorphoses, a 15-book mythological narrative.

The noun metamorphosis means a change of form or structure, as well as the action or process of changing in form.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses is about transformation. In it, people are changed into animals, plants, rocks, and streams by the gods.

The book is an important source of information about classical mythology, but is also interesting to read because of its many surprising details.

For centuries, Western art, literature, and music have been influenced by Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Among writers who were inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses, all of whom are represented in the TU Library collection, are Dante Alighieri, Giovanni Boccaccio, Geoffrey Chaucer, and William Shakespeare.

Here are some lines from Ovid’s Metamorphoses which have entered general use in English:

We two are a multitude.

- Book I, line 355

The middle way is safest.

- Book II, line 137

My riches make me poor.

- Book III, line 466

Fire suppressed burns all the fiercer.

- Book IV, line 64

Nature has given no one ownership

of sunlight, air, and water!

- Book VI, lines 350–351

I see, approving,

Things that are good, and yet I follow worse ones.

- Book VII, lines 20–21

No joy is ever complete, and sorrow always

Intrudes on happiness.

- Book VII, lines 453–454

The gods look after

Good people still, and cherishers are cherished.

- Book VIII, line 724

Only the poor man counts his cattle.

- Book XIII, line 824

Nothing is permanent in all the world.

All things are fluent; every image forms,

Wandering through change.

- Book XV, lines 177–178

Time, the devourer, and the jealous years

With long corruption ruin all the world

And waste all things in slow mortality.

- Book XV, lines 234–236

What we call birth

Is the beginning of a difference,

No more than that, and death is only ceasing

Of what had been before.

- Book XV, lines 255–257

Times are upset, we see, and nations rise

To strength and greatness, others fail and fall.

- Book XV, lines 420–422

In August 1971, the American poet John Hollander wrote about Ovid:

To many critics, the “Metamorphoses” has seemed a poem of evasion. Ovid’s world, in which, as Gilbert Murray put it, “every plant and flower has a story, and nearly always a love story,” is in its way magnificent garden. But most neoclassical sensibilities have found such a garden a vacation‐spot at best and its growing things unrooted in any earth. “His criticism of life is very slight,” Murray concluded; “it is the criticism passed by a child, playing alone and peopling the sum mer evening with delightful shapes, upon the stupid nurse who drags it off to bed.”

That Ovid’s rich overgrowth should be thought a moral desert reflects on literary history: transformation is Ovid’s subject; and yet his own transformation, into literature, of Greek fables originally of the pro foundest religious significance, com pletes a process of abstraction of myth from meaning that had been going on for centuries. “A myth in its simplest definition, is a story with a meaning attached to it, other than it seems to have at first; and the fact that it has such a meaning is generally marked by some of its circumstances being extraordinary, or, in the common use of the word, supernatural.” This definition will hardly be acceptable to anthropol ogists, or to all classicists; it comes from John Ruskin’s own mythopoetic work, “The Queen of the Air” and embodies the sense of myth that poets have. It was this sense which impregnated the Renaissance ground in which Ovid’s poetry was to flourish so meaningfully as well as elaborately.

Some readers may be surprised to find that parts of Ovid’s Metamorphoses are as violent as Game of Thrones or other action and adventure television series.

There has been extensive recent academic scholarship about this theme in Ovid, for example Transforming Violence in Ovid’s Metamorphoses by Professor Rachael Cullick of Oklahoma State University.

Part of the abstract of Professor Cullick’s study follows:

Focusing in this paper on episodes that feature this awareness, I argue that consideration of Ovid’s representations of violence on their own terms sheds light on how he explores the effects of power and the human experience of violated autonomy. These are themes at work more broadly in Latin literature under Augustus and the early empire, and they reflect a concern with finding ways to envision autonomy under an emperor. The idea of the self as inviolate runs through Roman culture, and our own, but it was, of course, an idea that only applied to free men in antiquity. In a context that always allows for the possibility of violation, which would include the poetic context of the Metamorphoses and the actual context of women and slaves, one can explore how to maintain (or regain) autonomy and create new narratives that allow for value and beauty under the constraints of overwhelming power…

This paper begins with the question posed by Marsyas: “Why do you remove me from myself?” (‘quid me mihi detrahis?’ 6.385). This can rightly be read as representing poetic detachment (and see Feldherr 2004 on comic and parodic elements in the episode), but Ovid’s representations of metamorphosis go beyond that. In fact, Marsyas’ question is central to understanding Ovid’s representations of violence and metamorphosis: here, gruesomely, it is the satyr’s skin that is being removed from the rest of his self, but Ovid consistently focuses not just on the potential loss of self inherent in his transformations, but precisely on the victims’ awareness and observation. Furthermore, I would argue, Ovid suggests that this awareness itself, so strikingly demonstrated by Marsyas, can transform the transformation.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)