On Wednesday, 30 June 2021, Thammasat University students are cordially invited to join a free webinar on Hong Kong’s National Security Law: One Year On.

The Thammasat University Library collection includes several recent books about different aspects of life in Hong Kong.

The event begins at 9am Bangkok time and is hosted by the Asia Institute at the University of Melbourne, Australia.

For further information or with any questions, students may contact the presenters at the email address:

melissa.conleytyler@unimelb.edu.au

As the Asia Institute website explains,

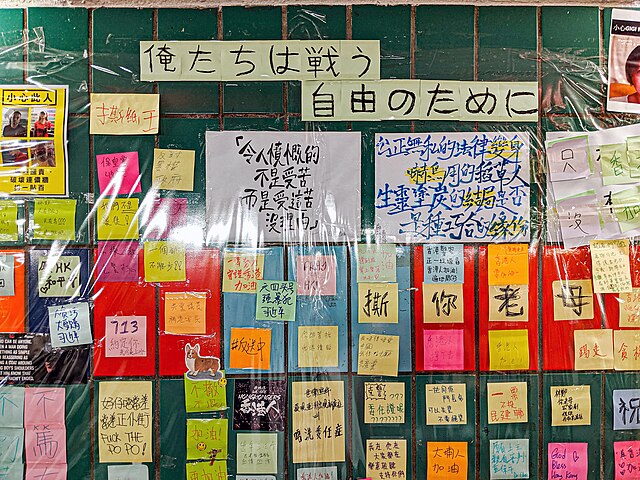

Passed on 30 June 2020 by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee in Beijing, the National Security Law was seen as a response to the 2019 pro-democracy protests that rocked Hong Kong. The law created four new crimes: secession, subversion, terrorist activities and collusion with foreign forces. All four are broadly-worded and could be used to punish pro-democracy advocates and other peaceful critics of the Hong Kong government and Beijing.

One year on, this webinar will look at how the National Security Law has been used, with those arrested including youth activists, media moguls and political opponents. It will look at the impact of the law on peaceful political speech and as a test case for judicial independence in Hong Kong.

It showcases the latest edition of the Melbourne Asia Review on Human Rights and Civil Society in Asia.

Presenters will include Professor Thomas E. Kellogg, Executive Director of the Georgetown Center for Asian Law; Professor Mark Wang, Director of the Centre for Contemporary Chinese Studies at The University of Melbourne; Melissa Conley Tyler, Research Associate at the Asia Institute, The University of Melbourne; and Lydia Wong, the pen name of a political science scholar and former rights activist.

Ms. Wong and Professor Kellogg have already produced an assessment in February of the results of the National Security Law, published by the Center for Asian Law, The Georgetown University Law Center, Washington, D.C. the United States of America.

The Executive Summary of the report reads in part:

The National Security Law (NSL) constitutes one of the greatest threats to human rights and the rule of law in Hong Kong since the 1997 handover.

This report analyzes the key elements of the NSL, and attempts to gauge the new law’s impact on human rights and the rule of law in Hong Kong.

The report also analyzes the first six months of implementation of the new law, seeking to understand how the law is being used, who is being targeted, and which behaviors are being criminalized. The report is based on interviews with Hong Kong actors from various backgrounds, and also a wide-ranging review of the public record, including press reports, court documents, and other publicly-available sources.

Our key findings include:

- The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) government and the central government have made vigorous use of the NSL over the past seven months, with over 100 arrests by the newly-created national security department in the Hong Kong police force, mostly for NSL crimes.

- The threat posed to Hong Kong’s autonomy by the passage of the NSL by the central government is significant. At the same time, the creation of hybrid Mainland-Hong Kong national security bodies also directly threatens the Basic Law’s One Country, Two Systems framework and the oft-cited mantra of Hong Kong people ruling Hong Kong.

- According to publicly-available information on the cases that have emerged thus far, the vast majority of initial NSL arrests would not be considered national security cases in other liberal constitutional jurisdictions. This raises questions about whether Hong Kong is beginning to diverge from its historically liberal, rule of law legal and political culture.

- The cases that have emerged thus far raise serious concerns that the NSL is being used to punish the exercise of basic political rights by the government’s peaceful political opponents and its critics. Prosecution of individuals for exercising their rights to free expression, association, or assembly would violate Hong Kong and Beijing’s commitments under international human rights law.

- The impact of the NSL has been felt well beyond the more than 100 individuals who have been arrested by the Department for Safeguarding National Security (NSD). According to our interviews, self-censorship – among journalists, academics, lawyers, activists, and members of the general public – has emerged as a serious problem, one that could blunt Hong Kong’s longstanding tradition of freewheeling and robust public debate.

- Many that we spoke to also feared that the NSL would have an impact on the day-to-day work of Hong Kong’s government bureaucracy, and that NSL values and norms could shape policy formation in potentially damaging ways for years to come.

If current trends continue, Hong Kong could become a fundamentally different place, one that enjoys fewer freedoms and rights, with social, political, and legal institutions that are less vibrant, less independent, and less effective than they once were. As our analysis makes clear, the future of the One Country, Two systems model, and of Hong Kong’s autonomy, are in jeopardy.

This report proceeds in two parts. In Part One, we offer a human rights and rule of law analysis of the NSL itself. We pay special attention to the ways in which the NSL infringes on the autonomy of Hong Kong’s core political and legal institutions, and also the ways in which the newly-created criminal provisions could be used to punish the peaceful exercise of core political rights, in potential violation of both the Basic Law and the obligation of the Hong Kong government to adhere to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

In Part Two, we focus on the implementation of the law thus far. Since its implementation on June 30, 2020, the law has been used in three key ways: to limit certain forms of political speech, with a particular focus on pro-independence speech and key slogans from the 2019 protests movement; to limit foreign contacts, and in particular to break ties between Hong Kong activists and the U.S. and European governments; and to target opposition politicians and activists, many of whom are longtime pillars of Hong Kong’s political scene.

Also in Part Two, we analyze some of the most high-profile arrests that have been carried out under the NSL to date, including the August 10, 2020 arrests of Jimmy Lai and Agnes Chow; the September 2020 arrest of prominent pro-democracy activist Tam Tak-chi, and his subsequent indictment for sedition under the Crimes Ordinance; and the January 2021 arrests of 53 pro-democratic politicians and activists for taking part in a primary election in July 2020. In all of these cases, we raise serious concerns about the potential for those arrested and charged to potentially be punished merely for the exercise of their core political rights, including the rights to expression, association, and assembly as protected by Hong Kong’s Basic Law.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)