A book newly acquired for the Thammasat University Libraries collection should appeal to all readers who care about the international image of Thailand in world history.

Inseparable: The Original Siamese Twins and Their Rendezvous with American History is by Professor Yunte Huang, who teaches English at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Lingnan University, Hong Kong.

This new acqusition joins others in the TU Library about the same subject.

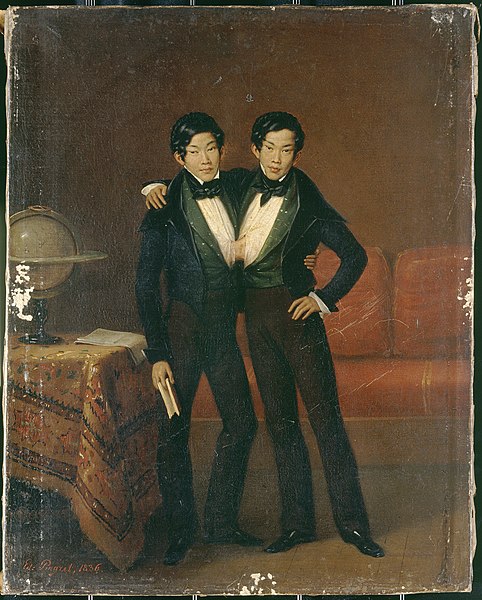

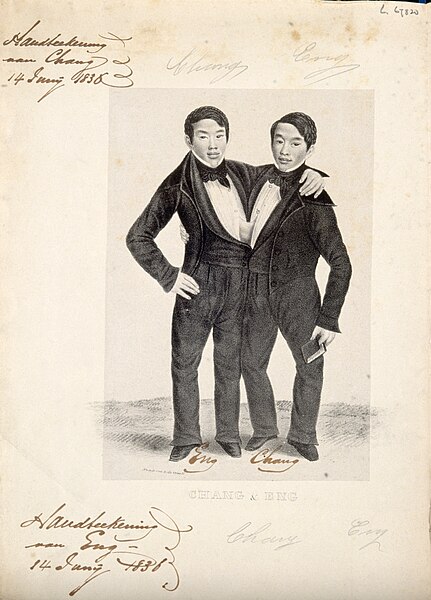

His book gives historical context to the celebrated life story of In and Chun (1811-1874), conjoined twins born in 1811 in the Mae Klong Valley, Samut Songkhram Province, Siam, during the reign of King Rama II. Their father, Ti-aye, a fisherman, was of Chinese origin and their mother, Nok, possibly of Chinese-Malay background, so the boys were known as the Chinese twins in their homeland. Joined at the sternum by a piece of cartilage, the boys were athletic and enjoyed playing badminton and performing tumbling tricks despite their disability. This caught the eye of a traveling British merchant who exported them to America to exhibit them in sideshows.

Renamed Chang and Eng, they would later convert to Christianity and adopt the family name Bunker, as they settled down in North Carolina. They both married and had several children, some of whom fought for the Confederacy in the American Civil War. They became so famous as performers that a new term, Siamese twins, was used until fairly recently to describe conjoined twins.

The book examines the paradox of how Chang and Eng Bunker, although themselves targets of race prejudice, owned African-American slaves in the pre-Civil War era. He also notes how they boldly fought for their own independence from abusive employers a few years after they arrived in America.

In an online interview, Professor Huang was asked:

If you could have met Chang and Eng, what one thing would you have asked them?

His reply, in part:

My own question for them would be, “Why did you never go back to Siam?” As an immigrant, I can feel in my bones the pang of nostalgia, memories of my old country running as deep as genetic coding. After leaving their family in Siam at the young age of 17, the twins never went back. I’m curious to know why.

To another interviewer, he commented:

“The biggest thing I take away from their story,” Huang said, “is the sense of what does it mean to be a human being. For them, they have no choice. So-called individualism will not work for them. They have to do everything together. … Being human for them means literally being more than one all the time. This kind of rugged individualism, which is so cherished in American culture, may require another look in light of their story.”

Here is an excerpt from Professor Huang’s book:

At the time of the twins’ wedding, some local folks wagered over how long the marriage could last and whether such a “freakish union” would produce any offspring. In their mind, bestiality was godforsaken, unnatural, and surely doomed to infertility. They also wondered how long the Yates sisters could stand the ignominy of having to bed two swarthy Asian freaks. James Hale predicted that unless the twins were separated, the marriage would not stand a chance. “Depend upon it,” he wrote to Charles Harris, “the result will be, a desire to attempt a surgical operation upon themselves.”

Those skeptics might have been surprised to know that the twins had indeed considered surgically untying themselves so that they could lead “normal” lives with their respective wives. It was their wives, however, who vehemently opposed such a move. According to some biographers, the twins, prior to their wedding, had consulted with physicians in Philadelphia and were ready to go under the knife. Aghast at the news, Sarah and Adelaide begged the men not to follow through with the dangerous procedure and reassured the men that they would be happy to marry them “as they were.”

The skeptics must have been even more surprised when they heard, ten months after the wedding, that each couple had produced a “fine, fat, bouncing daughter.” On February 10, 1844, Sarah and Eng became proud parents of a baby girl named Katherine; only six days later, Adelaide and Chang welcomed into the world a baby girl named Josephine. If there was any lingering doubt about the procreative aspect of the unions, there would be even more evidence to put the matter to rest: In their lifetime, the two couples would produce twenty-one children in total, with Eng and Sarah claiming eleven and Chang and Adelaide, ten. Out of these twelve daughters and nine sons, two would die at young ages from accidents, while two were deaf and mute. There were no twins, let alone conjoined twins or babies with any other discernible deformity…

A year after the birth of their first children, the twins and their wives celebrated the arrival of two more additions to the brood, born again only about a week apart: a baby girl named Julia for Eng and Sarah on March 31, 1845, and the first boy, named Christopher, for Chang and Adelaide on April 8. As the family grew, the house in Traphill became too small for them. In the spring of that year, Chang and Eng purchased a farm in nearby Surry County for $3,750. Straddling bubbling Stewart’s Creek outside the village of Mount Airy, this 650-acre farmland would become their Xanadu—or, more pertinent and closer to home, their Monticello.

On this new land, Chang and Eng—two brothers formerly sold into indentured servitude and treated no better than slaves—began farming by using black slaves. Here our story takes a significant turn, entering what Primo Levi called “the gray zone” of humanity, a treacherously murky area where the persecuted becomes the persecutor, the victim turns victimizer.

The first slave Chang and Eng owned, as mentioned earlier, was Aunt Grace, the ancestor of Brenda Ethridge, who attended the 2003 Bunker reunion. Legally known as Grace Gates, and born a slave in Alabama around 1790, Aunt Grace was sold to North Carolina at a young age and became the property of David Yates. Chang and Eng received her as a “wedding gift,” the same way that the nameless black servant standing behind Alabama circuit judge Sidney Posey, presiding over the assault case against the twins years earlier, had been a wedding present from the young judge’s in-laws. Known for her exceptionally large feet, Grace would assume the slave–nanny role and exert a large influence in the twins’ family, nursing all of the Bunker children as well as her own.

Soon after their relocation to Surry County, the twins began to purchase more slaves and even engage in slave trading. What is unquestionably clear is that the twins by this time had adopted the mindset, in all its permutations, of the oppressor class, the whites who owned slaves. In September 1845, they bought from Mount Airy planter Thomas F. Prather two black girls, aged seven and five, for $450, and from another neighbor a three-year-old boy for $175. Within just a few years, they had eighteen slaves. Out of these eighteen, according to the 1850 census, more than half were younger than eight years old. As Judge Graves admitted candidly, “Some few of their slaves were valuable to them for their present ability to labor; but much the greater number of them were an absolute burden but very valuable on account of the marketable price and prospective usefulness.” According to the twins’ descendant Melvin Miles, Chang and Eng would buy slaves younger than eight, keep them, and work them until they were in their early twenties, when they would be sold or traded for younger ones to carry on the work. With very few exceptions, they would not keep a male slave older than twenty-five, because “the twins thought that by then the male slaves were of the mindset of trying to escape or rebel against their owners.” Perhaps the twins remembered the horror of the Nat Turner revolt in 1831. Female slaves, by contrast, would be kept for as long as needed, because they were less likely to run away or to rebel, and they would bring additional value when they had babies—the so-called increase. Aunt Grace, for instance, gave birth to nine children, three of whom—Jacob, Jack, and James—survived and became the property of her masters. In fact, Grace’s three sons all assumed the Bunker name, according to the 1870 census.

Living in squalid cabins, the slaves were divided into “house slaves” and “field slaves.” The former, including Aunt Grace, worked mostly around the houses, helping to cook, clean, sew, nurse babies, and do other domestic chores. The field slaves would rise before dawn and work in the field till sunset. How the twins treated their slaves was a contentious topic both during their lifetimes and after their deaths. There were accounts that portrayed them as humane and kind, while others described them as “severe taskmasters.” According to Judge Graves, whenever the twins took long trips, they would always bring gifts for each member of the family, “not even forgetting the colored servants down to the youngest.”8 In the field, they also patiently taught the slaves some of the new farming techniques they had learned from agricultural magazines. The twins were allegedly among the first farmers in North Carolina to produce “bright leaf” tobacco, and they taught the slaves how to use their newly acquired press to make “plug” chewing tobacco. Possum-hunting being one of their favorite sports, the twins would frequently take some of the slaves out with them on early mornings for expeditions, which were recreational to them but not necessarily to the slaves.

These descriptions of the so-called harmonious relationship between masters and slaves, suggesting that the twins “did not drive their slaves but supervised them,” were complicated by allegations to the contrary. The first of these negative reports appeared in a newspaper article published in the Greensborough Patriot in 1852. The author of the article, who signed himself merely “D.,” did a profile of the twins, describing them as shrewd and industrious businessmen with belligerent and fiery dispositions. He claimed that the twins had once split “a board into splinters over the head of a man who had insulted them” and were “fined fifteen dollars and costs…Woe to the unfortunate wight who dares to insult them.” This prelude led to a more devastating revelation: “When they chop or fight, they do so double-handed; and in driving a horse or chastising their negroes, both of them use the lash without mercy. A gentleman who purchased a black man a short time ago from them, informed the writer that he was ‘the worst whipped negro he ever saw.'”

Such an unflattering depiction of them as cruel masters drew an immediate response from the twins, who were acutely aware of the importance of public image. They shot off a long letter to the newspaper, defending their own character and integrity and objecting vehemently to the article’s claims:

The portion of said piece relating to the inhuman manner in which we had chastised a negro man which we afterwards sold, is a sheer fabrication and infamous falsehood. We have never sold to any man a negro as described, except to Mr. Thos. F. Prather, who denies the truth of said accusation, or of ever having told any person that which the author of said communication says he heard. We are well aware that to some who have not seen us, we are to some extent an object of curiosity, but that we were to be objects of such vile and infamous misrepresentation, we could not before believe.

Along with the letter, the twins attached an endorsement by thirteen local citizens and neighbors attesting to the truthfulness of their statement, signatories who included Thomas Prather, from whom the twins had made their first purchase of young slaves and to whom they had now sold an older one.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)