Thammasat University students are cordially invited to participate in a free Zoom conference on Wednesday, 18 August 2021 starting at 9am Bangkok time.

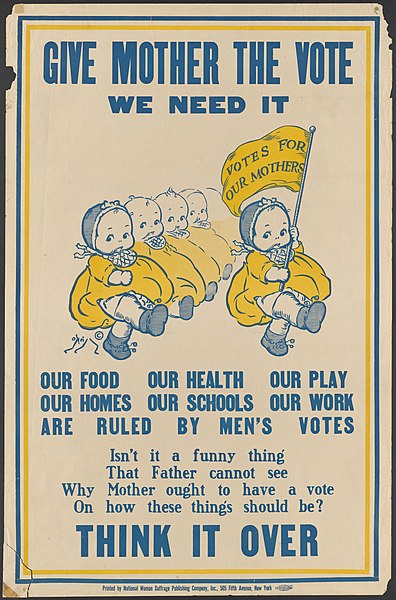

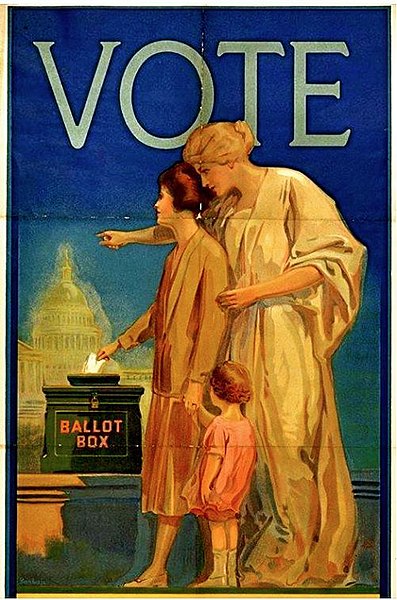

Hosted by The Committee on Gender Equality and Diversity and the Gender Studies Programme at the University of Hong Kong (HKU) in conjunction with a U.S. Consulate General Hong Kong and Macau exhibition celebrating the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in the United States, the event is entitled Listening through the Unheard: A Reflection on 100 Years of U.S. Women’s Suffrage and its Connections with Asia.

The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution granted the right to vote to women across America.

The panel discussion examines the subject in comparative, political, transnational and multicultural perspectives.

The Thammasat University Library collection includes several books about women’s rights.

For further information or with any questions, kindly write to this email address:

gchallen@hku.hk

Students may register to participate at this link:

https://hkuems1.hku.hk/hkuems/ec_regform.aspx?guest=Y&UEID=77111

The event website notes that the panelists will include Professor Louise Edwards, Emerita Professor of Chinese History at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Sydney, Australia.

The TU Library owns a number of books by Professor Edwards.

Her fields of research include Asian history, culture, gender, sexuality, literature in Chinese, as well as government and politics of Asia and the Pacific.

She has served as President of the Asian Studies Association of Australia and has taught at The University of Hong Kong, University of Technology Sydney, Australian National University, Australian Catholic University and the University of Queensland.

Another speaker at the 18 August event will be Professor Martha S. Jones, whose writing is also represented in the TU Library collection.

Professor Jones teaches history at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

She is a legal and cultural historian.

Her personal website explains:

I am a historian, writer, and commentator who focuses on how black Americans have shaped the history of American democracy. This theme runs through my scholarship, commentary and creative projects.

Acting as another panelist and moderator will be Dr. Brenda Rodriguez Alegre, a lecturer in the Gender Studies Programme, School of Humanities, The University of Hong Kong.

According to her official faculty homepage,

Dr. Brenda Rodriguez Alegre was born in the Philippines. She is a registered psychologist.. She graduated with Magna Cum Laude honors with a PhD in clinical psychology. Her MA thesis and PhD in clinical psychology dissertation were about transgender women… She is a Resident Tutor at Lap Chee College, University of Hong Kong, and a Lecturer at the University of Hong Kong where she teaches Sexuality and Gender, perhaps one of the few if not the only trans identifying academics in Hong Kong…

Last year, Professor Edwards published an article in Humanities Australia: The Journal of the Australian Academy of the Humanities, analyzing how after the creation of the new Republic of China, Asia’s first republic, in 1912, popular art images in a series of One Hundred Illustrated Beauties were adapted to show societal change in the modern era, including:

images of young women attending schools, delivering speeches, and reading newspapers—a celebration of the productive, informed and civically-engaged citizen. The beautiful women that emerged from their ink brushstrokes drove cars, flew planes, rode in trains and, in their leisuretime played tennis, ping-pong, golf, bowls and croquet. The pining, wistful and self-sacrificing beauties that dominated the traditional One Hundred Beauties genre were being transformed, while not entirely disappearing. These old-style beauties were steeped in literati culture and reflected Confucian values and admired the ancient, the past and women who largely stayed cloistered in boudoirs and private gardens… Productive labour by ordinary people was presented as ‘beautiful’. Simply being out in public for leisure, work or education became ‘modern’. Speed and motion displaced quietude and stillness as desirably modern states. Ding and Shen presented for their readers visions of citizens-in-action to contrast with the traditional, moral tales of imperial subjects depicted in the old-style One Hundred Beauties in collections by the late Qing artists, Qiu and Wu… Beautiful women dedicated their evenings to sewing the national flag, they taught their children to honour the same and to appreciate the borders of their new, sovereign nation as they looked at national maps… While Ding and Shen do present new women citizens as models of service to the nation and as radical participants in a raft of new public roles, their depiction of women’s engagement with the military conformed to age-old patterns of gender norms. Their revolutionary depiction of modern women in strikingly modern modes as modern mothers, politicians, professionals, businesswomen and travellers is coupled with the more traditional notions of women’s roles in the Republican military realm… The dearth of women soldiers in the modern versions of the One Hundred Beauties produced by two commercial artists committed to promoting new civic values for the new Republic, tells us that just as women in traditional China were welcomed into military roles in times of national, community or familial crisis; they were expected to exit the military domain and leave it for men once the wars were over. Shen and Ding encouraged women to take up new roles as students, teachers, journalists and farmers so quitting the battlefield did not mean returning only to conventional domestic roles as mothers, daughters and wives. But, by not including large numbers of women as modern soldiers, among the raft of radical images they published— they reinforced the idea that the modern military was a man’s sphere. Women’s modern Republican citizenship meant reassuring their readers at least about one aspect of gendered social-life that hadn’t changed—good times, peaceful times, stable times meant women did not have to become soldiers. As soldier beauties they could present an alluring vision of Chinese modernisation, but they were safely contained from the most radical challenges to the patriarchal gender order by references to the traditional ‘authorised women warriors’ who appeared only at times of national crisis… The reform-minded artists Shen and Ding were committed to their new Republic and its hopes to build a modern Chinese citizen capable of building a strong nation-state. Despite their depiction of a remarkable array of new roles for women, and new egalitarian values for all of the Republic’s new citizens, gender parity in military service posed a threat to the idea of male physical superiority, strength and martial prowess. Building a prestigious (manly) military meant keeping women out— persuading half the population to risk their lives in war relied in part on flattering them into believing this was some form of sex-based privilege or skill unique to men. This early Republican reluctance to include modern women as part of the modern military, would be soon be challenged by the failure of the Republic to bring a lasting peace to China. As warlords vied for control over territory and wealth, dreams of a peaceful China with a modern society, delineated by gender nonetheless, faded. In the late 1920s with the Nationalist Party’s battle to defeat the warlords and reunite a fractured China, women were welcomed into the Nationalist Army, received specific training in separate military colleges, and even wore the same uniforms as men…

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)