On Wednesday, 6 October at 4:30pm, the Faculty of Social Policy & Development, Thammasat University presents a special Zoom public lecture on Zombie lives? Urban refugees and the informal sector.

The Thammasat University Library collection includes many books about different aspects of refugee status and also about zombies.

As TU students know, zombies are mythological beings resulting from when dead people supposedly return to life.

The term originates in Haitian folklore and has become popular in fantasy and science fiction literature.

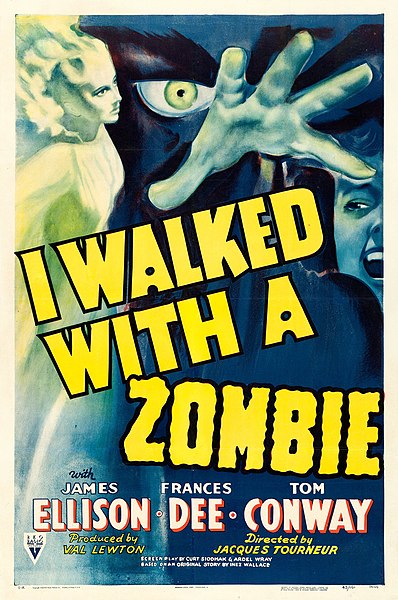

Zombies were essential parts of the horror films Night of the Living Dead (1968) and Dawn of the Dead (1978) as well as Michael Jackson’s music video Thriller (1983).

In the late 1990s, the video games Resident Evil and The House of the Dead renewed interest in zombies in popular culture.

In Asia, such films as the zombie comedy Bio Zombie (1998) and action thriller Versus (2000) were followed by Western zombie movies, including 28 Days Later (2002), the Resident Evil and House of the Dead films, the 2004 Dawn of the Dead remake and the British zombie comedy Shaun of the Dead (2004).

In 2014, The Wall Street Journal reported that zombie studies had become a widespread subject for academic research projects and theses.

At the 6 October event, the speaker will be Professor Itty Abraham, an expert on migration from the National University of Singapore.

The TU Library owns books written and coedited by Professor Abraham. His research interests include international relations, science and technology studies, and postcolonial theory.

Professor Abraham will analyze the interaction between migrants and the state and related issues of identity from a political perspective in an increasingly digitalized world.

The lecture moderator will be Dr. Sorasich Swangsilp of the Faculty of Social Administration, Thammasat University.

Students may register for the event at this link:

https://forms.gle/ZtS56JrQq8hzDHR36

Join Zoom Meeting

https://zoom.us/j/97885495870…

Meeting ID: 978 8549 5870

Passcode: spd442

In a research article published in March of last year, Professor Itty noted,

Forced migrants have been crossing national and imperial borders in Southeast Asia since the time of the Japanese occupation (1942–45) and the ensuing period of decolonization. Border-crossings took place by land and sea, but especially the former. Many forcibly displaced people were assimilated into border communities and became accepted as legal residents with the passage of time. A flood of refugees entered Southeast Asia and Hong Kong with the formation of the People’s Republic of China, beginning in 1949. Refugee admissions largely took place in a legal vacuum. Most independent Southeast Asian countries, with the particular exception of the Philippines (1981), neither signed the United Nations (UN) Refugee Convention of 1951 nor crafted domestic legislation on refugees. Some regional countries participated in the Asian African Legal Consultative Committee’s deliberations on refugee policy, leading to the Bangkok Principles (1966), a non-binding statement of state obligations and recommendations on dealing with refugee populations. Turning Point Most observers would agree that the turning point with regard to regional refugee policies was the multiple military, political and humanitarian crises that came to a head in the mid-1970s with the reunification of Vietnam and fall of the Cambodian monarchy. It was from this moment that Southeast Asian countries collectively resisted acknowledging asylum seekers as persons entitled to special consideration under customary international law and insisted that finding a solution to the ‘Indochina refugee crisis’, as it came to be called, was the responsibility of the international community. In some cases, Southeast Asian states returned involuntarily asylum seekers to their country of origin; in other cases, they defined their role as countries of transit and temporary residence for refugees who would be resettled elsewhere in the world. This dominant understanding—of Southeast Asian states as countries of transit and temporary residence—has shaped regional policies with regard to refugees since that time. Transitory and Temporary This understanding is no longer tenable. While recent developments at the global level may have exacerbated the problem (the rise in nationalist and populist sentiments in the Global North that have led states increasingly to be unwilling to fulfil their legal obligations for refugee resettlement), Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia have been de facto countries of final destination for refugees since at least the mid-1980s. These governments have been loath to accept this understanding of their status and continue to shape policies—to the extent they exist—based on assumptions of transitory impermanence. Moreover, received understandings of the 1970s crisis as a starting point for the Indochina refugee crisis have led to institutional and public amnesia on pre-Indochina refugee movements and earlier incorporations of displaced and moving communities into local populations. There is also little acknowledgement of how the post1970s geopolitical context informs how contemporary states in the region respond to refugee movements. These combined factors—an unwillingness to acknowledge their change of status and the loss of historical memory of refugee assimilation—continue to shape policy in the primary refugee receiving states in the region. Yet, almost every decade since the 1980s has seen at least one wave of forced migration into neighbouring countries, with Myanmar being the prime and continuing source of refugee outflows in the region. The main refugee-hosting countries of Southeast Asia have hosted refugee populations for decades: Thailand for at least thirty-five years, Malaysia for at least twenty-five years, and Indonesia for at least fifteen years. In the absence of formal acknowledgment of this condition, practical experience gained as a result cannot be systematized nor incorporated into institutional practice. This hands-off approach leads to multiple sovereignties in practice, with informal and socially grounded authorities contesting the formal authority of the territorial state around refugee settlements. Seen from another standpoint, what this also means is that a generation (or more) of refugees in each country have grown up there and have no lived memory of any other place of residence. Repatriation to an ostensible homeland for these young people under these conditions is no longer a ‘durable solution’, but rather becomes forced exile from the only home they have known. This mismatch between policy and experience, reflected in the distance between state actions (and inactions) and social reality, should not be understood as anomaly or distortion but seen as a characteristic condition of the refugee environment in Southeast Asia. Moreover, such a gap is not entirely malign as it opens up a zone of ambiguity that, on many occasions, has been to the benefit of both refugees seeking sanctuary and means to livelihood and their hosts and civil society advocates offering informal protection and aid to asylum seekers. Refugee Locations Not all refugees are found in refugee camps. Many are residents of the margins of global cities. They may be also found in transit to a third country, in rural borderlands among ethnic kin, and incarcerated in detention centres as ‘irregular migrants’, among other sites. Each location is a distinct environment, making the character of interactions between asylum seekers and host communities hugely dependent on place.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)