Thammasat University students interested in gender studies, sociology, anthropology, human geography, area studies, cultural studies, psychology, heath science, social science, political science, and linguistics may find an Open Access book useful that is available for free download at this link.

Queer Roma is by Lucie Fremlova, an independent researcher on academia, social movements, and policy.

The Romani (also spelled Romany), known as Roma, are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group, traditionally nomadic itinerants living mostly in Europe, with populations in the Americas.

The TU Library collection includes several books about different aspects of Romani life and culture.

The Romani originate from the northern Indian subcontinent, from the Rajasthan, Haryana, and Punjab regions of modern-day India.

The Romani people are widely known in English by the term Gypsies, which is considered insulting by many Romani people due to its historical use to mean someone who commits illegal acts.

The Romani language is divided into several dialects, which together are estimated to have more than two million speakers.

By studying lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, intersex and queer (LGBTIQ+) Roma, Dr. Fremlova establishes that they are a more diverse population than previously suspected. She explains:

Roma are a diverse, heterogeneous, transnational ethnic minority scattered across continents as varied as Europe, North and South Americas, Australia, Africa and, according to some scholars, even Asia. Roma are often referred to as a nation without a territory or a state. In the European Union (EU) alone, Roma are estimated to number between 10 and 12 million: this makes Roma the largest ethnic/‘racial’ minority group. Roma differ significantly from continent to continent; from country to country; from region to region. This heterogeneity is also reflected in the different names coming under the umbrella term Roma… Historically, there has been an often-unacknowledged proximity between Roma and lesbian, gay, bi, trans, intersex and queer (LGBTIQ) people, reflected not just in a social, but also a linguistic affinity between queer argots such as Polari used by gay men and drag queens in the United Kingdom (UK) or a Lubunca and Kaliardà used by LGBTIQ communities in Turkey and Greece, respectively. Apart from borrowing from other languages, these queer argots both use elements of the Romani language. Despite this queer-Roma proximity, grounded in common experiences of stigmatisation and persecution of both groups discussed in Chapter Two, until very recently, queer Roma were not visible; or certainly not as visible as has been the case over the past decade. During this time, a discernible LGBTIQ Roma movement has emerged and mobilised across Europe: the latter section of this introductory chapter discusses this mobilisation. The visible presence of queer Roma at Pride events in European capitals and other cities, such as Prague, Cologne, Berlin, Madrid, Valencia, Strasbourg, Bucharest, Kyiv, Budapest or London, which came to a temporary halt in 2020 due to the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic, is another aspect of the enormous diversity among Roma of multiple, intersecting identities – whether they are linked to ethnicity/‘race’, sexuality, gender identity or other categories of identification. As this book will show, contrary to so-called popular beliefs and opinions, Roma of minority sexual and gender identities, who identify as queer, have always been present within the social matrix of the various subgroups and in all walks of life. And not just that: the rich, multi-faceted lived experiences of queer Roma presented in this book dispel myths about the presumed compulsory heterosexuality, homophobia and sexual backwardness of Roma. Yet, despite this ever-present heterogeneity among Roma, non-Roma and majority societies have historically seen and treated Roma as a homogeneous ethnic monolith, to whom they have attributed a negative group identity. Given this overwhelmingly negative treatment of Roma by non-Roma throughout the history, it is not a coincidence that even in the 21st century, Roma remain one of the most discriminated against ethnic/‘racial’ minority groups in Europe. Roma continue to face high levels of ethnic/‘racial’ discrimination, socio-economic marginalisation and exclusion also in other parts of the world, for instance, the United States (US). In countries as varied as Slovakia, Romania, Bulgaria and Denmark, the COVID-19 pandemic has served as a magnifying glass, uncovering the actual extent of racial inequalities and anti-Romani racism; and the discrimination that Roma are subject to at the hands of majority societies. For instance, lack of running water in many, often overcrowded Romani settlements, ghettos and dwellings across Europe has meant that Roma have been contracting COVID-19 at a higher rate than non-Roma. This has led to an increased number of arbitrary acts of over-policing by law enforcement agencies and the army, as well as cases of police brutality.

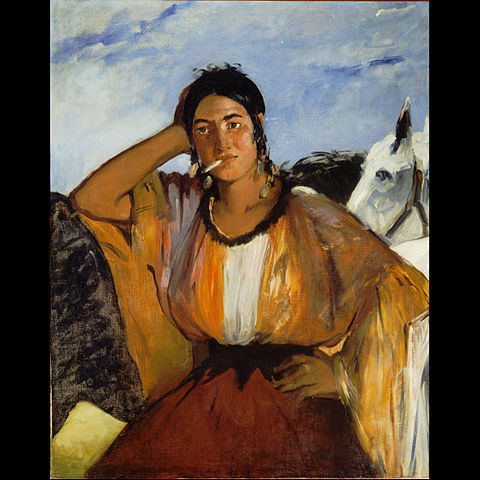

The response to Roma by non-Romani individuals, institutions, organisations, governments and even academia has tended to be very polarised. As I will discuss later in this book, in the popular imagination of non-Roma, Roma have either been portrayed as villains or romanticised ‘bon sauvages’. This dichotomy of vilifying representations on the one hand and romanticising ones on the other has been instrumental in generating and maintaining stereotypical and damaging misrepresentations and perceptions of Roma among non-Roma, as well as a stigmatised, fixed ethnic identity… The danger lies in that stereotypical portrayals that flatten a particular people and their experiences by constantly showing them as only one thing over and over again turn the people into a single story: an incomplete stereotype which robs them of dignity by emphasising how distinct and different they are. Such historically flattened portrayals and representations of Roma have led to social stigmatisation of Roma whom non-Roma perceive as fundamentally distinct, different from the white, non-Romani majority and the rest of society both in terms of biology and culture. Over the past decades, there has been a lot of extreme negative media coverage of Roma. These single, flattened stories about ‘Roma leaving rubbish and stealing stuff’ have become a source of television entertainment in the form of reality TV shows and investigative documentaries that spread misinformation about Roma, produced by commercial channels across Europe and the US, as well as by European public service broadcasters such as Czech Television or the BBC. Since many Roma do not want to be associated with such negative portrayals for fear of being stigmatised and racially persecuted even further, they often decline to be identified, hide or deny their ethnicity altogether. Non-Roma have tended to see and treat Roma as a threat, risk to personal safety and societal, national and trans-national security. Within the neoliberal market-oriented political arena, with its emphasis on free trade, deregulation, privatisation, public service cuts due to austerity measures since the 2008 financial crises and the COVID-19 pandemic starting at the turn of 2019 and 2020, nation states have often tended to make Roma hyper-visible and used them as bargaining chips, or the proverbial sacrificial lambs to generate feelings of solidarity, collective identity and belonging among non-Roma. As this book will show, even in academia, scholars, very often non-Roma, have incorrectly theorised Roma as an object of cultural essentialism stuck in time, anachronistic and antithetical to modernity, or even post-modernity; and trapped within a purely ethnic frame of reference. Such a collective conception of ethnic identity has engendered an approach whereby members of this group have been reduced to possessing the same or similar sets of assumed characteristics and values determined by a fixed ethnic identity. However, such a conceptualisation has never reflected the everyday lived realities of Roma; and, for that matter, those of queer Roma even less so.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)