Thammasat University students interested in public international law, economics, business, political science, criminology, development studies, and related subjects may find an Open Access book useful that is available for free download at this link.

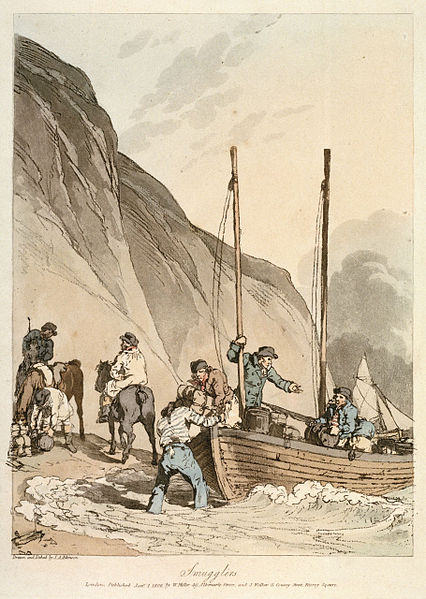

The Routledge Handbook of Smuggling offers an overview of research about international smuggling, including such themes as mobility, borders, violent conflict, and state politics.

The TU Library collection includes several books about different aspects of international smuggling.

Many students may be familiar with stories about smuggling of illegal materials such as wildlife, weapons, and drugs. However, some nations must also deal with counteracting smuggling of rice and other materials that under normal conditions would be considered legal.

There is also human smuggling and irregular migration. As of 2017, Myanmar was determined to be is the largest exporter of low-skilled labor in Southeast Asia.

Many years of chronic underdevelopment and conflict, as well as the extensive border with Thailand, have created opportunities for human smuggling. There are approximately five million migrants from Myanmar in Thailand, many of whom entered with the assistance of migrant smugglers. Thai companies rely on these smuggled laborers to work for low wages.

Originating in the bordering states of Mon and Kayin, these migrants travel to Thailand to repay family debts and support their families.

They opt to pay for transport providers to smuggle them across the border, because legally applying to register as a migrant in Thailand is costly and time-consuming.

Also, remaining in an illegal status makes it easier for workers to remain for unlimited stays and change employers, whereas if they were legally registered, they would have to regularly declare themselves and renew their visas, and if they changed jobs, their visas would immediately be cancelled by the Thai Ministry of Immigration.

To pay for journeys to Thailand, the Myanmar workers usually borrow money from relatives and pay off debts after they find work. Nearly all cross the border illegally without documents, but regularize their status after some time. In this way, nearly all migration from Myanmar to Thailand is irregular.

The website of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) notes:

The Challenge:

Within Southeast Asia, irregular migration is mainly driven by economic disparities. Even though borders are porous, UNODC estimates that over 80% of irregular migrants rely on smugglers. Around half a million migrants mainly from Myanmar (but also from Cambodia and Lao PDR) are estimated to be smuggled to Thailand each year. Fees for smuggling services are low, ranging from a few dollars to a few hundred dollars, meaning it is often cheaper to use smuggling services than regular labour migration systems.

What we do:

- UNODC enhances the capacity of law enforcement agencies to effectively identify professional smuggling networks and combat the smuggling of migrants by:

- Strengthening policy and legislative frameworks;

- Enhancing capabilities in identification, investigation and case preparation and prosecution;

- Increasing availability of information/data made on the nature and scale of migrant smuggling in the region; and

- Enhancing cooperation on a bilateral, regional and international level.

In 2019, The Bangkok Post reported:

Customs urged to act on sticky rice smugglers

The Internal Trade Department is urging border security and customs officers to crack down on the smuggling of unmilled glutinous rice by traders who want to profit off the high price of the commodity in the domestic market.

Whichai Phochanakij, director-general of the department, said most of the smuggled glutinous rice comes from Vietnam via Cambodia, before making its way across the border in Sa Kaeo, Chanthaburi and Buri Ram provinces.

“Tougher screening is needed, because there is high demand for glutinous rice in Thailand, which drives prices up,” he said.

“Conditions are ripe for traders to smuggle glutinous rice into the country, especially since durian and mangoes are currently in season.”

Unmilled glutinous rice can fetch up to 12,000 baht a tonne in Thailand — about 4,000 baht higher than in neighbouring countries.

“The high price of glutinous rice in Thailand should benefit our farmers,” said Mr Whichai.

“But huge amounts of contraband glutinous rice are flooding Thai markets. This could cause prices to plunge, and hurt the profits of Thai farmers.”

Chookiat Ophaswongse, the honorary president of the Thai Rice Exporters Association, said some Thai traders are working with smuggling syndicates to bring in glutinous rice from neighbouring countries.

“Thai glutinous rice fetches about US$900 (about 28,134 baht) per tonne in the export market, whereas Vietnamese glutinous rice sells for about $500 per tonne,” he said.

“As such, those who smuggle Vietnamese [glutinous] rice to be passed off and re-sold as a product of Thailand stand to gain almost 100% in profits.”

Mr Chookiat said drought has caused prices to soar, with glutinous rice reserves expected to drop to about two million tonnes (equivalent to about one million tonne of milled rice) this year — a 200,000-tonne drop compared to the same period last year.

The Thai market has been flooded with Vietnamese glutinous rice after China decided to stop importing the product from Vietnam because of strained ties between the two countries.

Mr Chookia also said that some Thai rice traders use their warehouses as storage facilities and transit points before they smuggle the rice onward to Malaysia, where it is sold at even higher prices.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) is the principal intergovernmental organization dealing with migration issues and the only global migration agency dealing with all aspects of migration.

Its publication, Trafficking of Fishermen in Thailand was supported by the United States Department of State, Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons.

It states, among other findings:

Working conditions on fishing boats are extremely arduous. Fishermen are expected to work 18 to 20 hours of back-breaking manual labour per day, seven days per week. Sleeping and eating is possible only when the nets are down and recently caught fish have been sorted. Fishermen live in terribly cramped quarters, face shortages of fresh water and must work even when fatigued or ill, thereby risking injury to themselves or others. Fishermen who do not perform according to the expectations of the boat captain may face severe beatings or other forms of physical maltreatment, denial of medical care and, in the worst cases, maiming or killing. Only a small percentage of foreign workers on fishing boats have proper documentation and work permits. On land, there is widespread use of informal “identification cards” which offer some protection from arrest by local police but have no legal basis in either Thai immigration or labour legislation. At sea, on boats leaving Thai waters, boat captains often hold fraudulent Thai Seafarer (Fisherman) books issued with the photo (but not the real name or bio-data) of each fisherman and usually do not release these to the crew while in foreign ports, thereby further diminishing any legal protection afforded by the document. While anti-trafficking legislation has been improved and Ministry of Social Development and Human Security (MSDHS) facilities established in Thailand to provide support to male victims of trafficking, including fishermen, the current framework requires men who have been trafficked to stay in shelters and does not permit them to work. The condition prohibiting work serves as a disincentive for male victims of trafficking to wilfully be identified as such. Since victims are not allowed to work to earn money, the system does not respond directly to the needs of male victims and results in many fleeing shelters, making it difficult to promote collaboration with law enforcement authorities to reduce human trafficking.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)