Thammasat University students are cordially invited to download a free Open Access book at this link that should be useful for readers interested in urban studies, city planning, sociology, and political science.

Cycling Pathways: The Politics and Governance of Dutch Cycling Infrastructure, 1920-2020 is by Dr. Henk-Jan Dekker, a historian who received his PhD in 2021 from Eindhoven University of Technology, the Netherlands.

The TU Library collection includes several books about different aspects of cycling as part of city planning.

Dr. Dekker’s research interests include the history of cycling policies in relation to culture, governance, and social movements, and the history of technology.

In an effort to fight climate change, many cities try to increase bicycle usage, to discourage vehicles that pollute the air. The Netherlands is seen as a pioneering country, along with China, among cycling nations. Dutch cyclists became successful in their struggle for a place on the road through a lengthy political struggle.

Dr. Dekker presents archival research showing the significant role of social movements and how they interacted with national, provincial, and urban engineers and policymakers to govern the distribution of road space and construction of cycling infrastructure.

He suggests, “Over the past few years, cycling has become considered the key to a sustainable and livable future for cities.”

Urban planners praise Dutch cycling as a pathway to a sustainable transport system. Just how the Netherlands achieved this national habit can help other nations who are seeking to boos cycling levels.

In many countries automobile and motorcycle interests have managed to bar cyclists and pedestrians almost completely from the road. In many cases there is also little to no investment in separate infrastructure for cyclists.

Why the Netherlands is different is explained in Cycling Pathways.

Dr. Dekker notes that governmental cycling policies were established about a century ago and since then, the bicycle has remained popular for recreation and commuting.

Regional and local policymakers believe in cycling, and activists keep promoting the activity to make the sport even more attractive and safe for all.

Planning ahead, in 2021, the Dutch Ministry of Public Works announced a National Future Vision for the Bicycle for 2020 to 2040.

Dr. Dekker argues that in the Netherlands, the

political appreciation of cyclists as citizens with rights (to infrastructure, safety, comfort, and so on) was stronger than elsewhere… Over nearly a hundred years, an extensive cycling network has been constructed in the Netherlands, for both recreational and utilitarian purposes. Today, constructing cycling infrastructure is considered a public good and a state task.

Yet this was not always the case. What changed?

How did providing for cyclists become a state task? Which actors shaped cycling policies and how did they do so? Cycling Pathways uncovers this governance process to shed light on the status of Dutch cyclists, both on the road and in policymaking from the 1920s to today. Over the past few years, cycling has become considered the key to a sustainable and livable future for cities. International experts and scientists like urban planners John Pucher and Ralph Buehler praise Dutch cycling as a success story – even a cyclists’ paradise – and an example of a pathway to a more sustainable transport system.

Dutch engineers and planners share their knowledge about planning for cyclists all over the world. As they are among the world’s most experienced cycling planners, this seems to make sense. On closer inspection, however, it is rather surprising. If Dutch experts are to help engineers in other countries, this presupposes that they know how to progress from these humble beginnings to a fully-fledged cycling system or network. This assumes historical knowledge about what led to this outcome. However, little has been written on the emergence of the Netherlands as a “cyclists’ paradise.”

How can the Dutch export their cycling knowledge to policymakers across the globe when so little is known about which government policies formed the Dutch cycling system? What role did the engineering community and social movements play? Should we ascribe a central role to non-governmental actors that tried to put cycling on the agenda? These questions need answers if we want to explain how the Netherlands became a nation of cyclists.

And yet, historians have hardly focused on what is often considered one of the quintessential Dutch features. In fact, cycling is so mundane in the Netherlands that its history is not considered a serious issue of study. This project fills a knowledge gap important to both an international audience interested in boosting cycling levels and a Dutch audience wanting to understand how cycling became so deeply ingrained in everyday practices. Studies of the history of urban cycling in the Netherlands are available, but none have covered the role of provincial and national governmental actors. While cycling activism has been studied, the role of citizens in social movements building expertise and political leverage requires further elaboration. Cycling Pathways addresses this gap by providing long overdue insights on mobility governance as a product of the interplay between engineering norms and ideology, politics, social movements, and users. This process of the mutual shaping of daily mobility in the Netherlands over the past century is central to this study. It shows the significant long-term consequences of mobility policies on aspects ranging from street design to the modal split and spatial planning. One of the insights of history – and mobility history in particular – is that decisions taken in the past often have far-reaching and unforeseen consequences. This mechanism is often referred to as path dependence: when decisions are built into concrete or asphalt, the results become hard to remove or modify.

A reflection on such policy choices made by various actors in the past, and the reasons behind them, can help us understand the present and shed some light on what (not) to do in the future. The bigger question Cycling Pathways raises is: Why did the Netherlands become such a successful cycling country? Multiple factors explain this.

Five key variables have been proposed by urban studies researchers:

Spatial structure and morphology, the availability of mobility alternatives, the cultural status of cycling, government traffic policy, and the influence of social movements.

Cycling Pathways focuses on two interrelated factors:

Government traffic policy and the influence of organized citizens in social movements. Together, these shape the division of road space – in particular, cycling infrastructure. While cycling infrastructure may not be a sufficient condition for a successful cycling country, research suggests that it is a necessary condition in today’s settings.

In high-automobility contexts, a combination of traffic-calming and traffic-separating measures are needed to make cycling broadly accessible to citizens. Historically, the distribution of road space and the provision of cycling space – sometimes seen as neutral and technical problems – are in fact political projects. The car’s dominant place on our streets is the outcome of a contested and long-term process in which other modes of transport were denied access to the road. Politicians, policymakers, and engineers have governed – and still govern – this process, as have user-citizens organized in social movements and the media. Despite opposition, in many countries pro-car interests have managed to bar cyclists and pedestrians almost completely from the road; in many cases there is also little to no investment in separate infrastructure for these road users. The story of the Netherlands is different – Cycling Pathways addresses why.

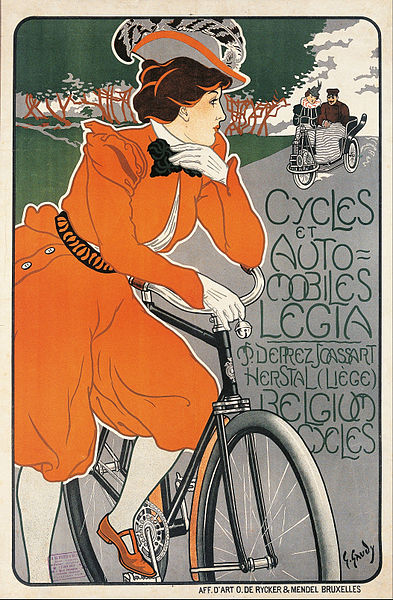

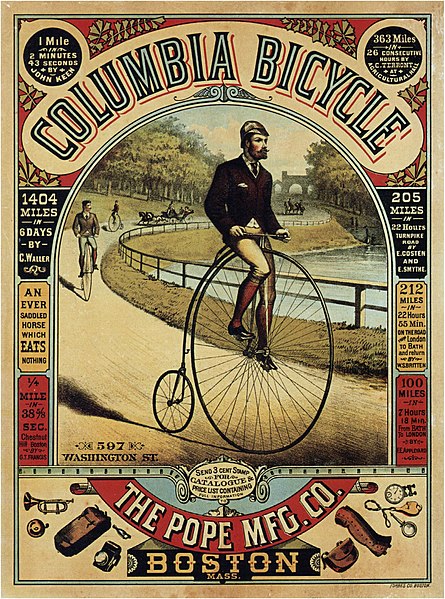

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)