The Thammasat University Library has newly acquired a book that should be useful for students interested in business, marketing, science, technology, sociology, and related subjects.

The Alchemy of Us: How Humans and Matter Transformed One Another is by Ainissa Ramirez, Ph.D., is an American materials scientist.

The TU Library collection includes many books on different aspects of materials science.

A materials scientist studies and analyzes chemical properties and structure of different natural and synthetic materials, including glass, rubber, ceramic, alloys, polymers, and metals.

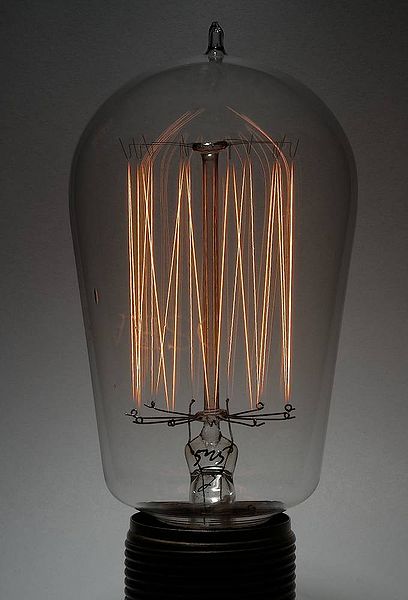

The Alchemy of Us examines the international impact of eight inventions, such as steel railroad tracks, light bulbs, telegraph wires, clocks, scientific glassware, and silicon chips.

One example of the influence of building railway lines, Dr. Ramirez suggests, is that it became easier to transport consumer products great distances. This led to the international celebrations of the Christmas holiday as occasions for exchanging gifts.

Developments in the chemical configuration of glass made it possible to standardize and improve the substance’s use in scientific laboratories, helping scientists to provide “understanding of how our bodies work, how the heavens move, and how other worlds exist in a drop of water.”

There are accounts of how lesser-known inventors worked to develop new technology, only to find themselves overshadowed by more famous figures such as George Eastman of Eastman Kodak and Thomas Alva Edison.

These less familiar researchers are cited to remind readers that scientific progress is not a matter of a few creative people, but many working at the same time to advance human understanding and achievement.

TU students of literature will be interested to know how the invention of the telegram influenced the writing style of the American author Ernest Hemingway.

Hemingway’s first job was as a newspaper reporter in Kansas City, at a time when writings by journalists were sent to the office by telegraph. He appreciated the telegraphic style of saying as much as possible in few words, and adopted this approach for his later writing of fiction.

As the author explained in an interview from 2020:

The Alchemy of Us explores how technology shaped us. It discusses the creation of eight materials science inventions—from steel rails to silicon chips—and then shows how those inventions changed culture. For example, readers will learn about some of the key inventors of the computer’s silicon chips, where this invention allowed computers to think. But readers will also see how the proliferation of computers is changing human cognition. Humans invent things, but then those things re-invent us. This is the premise of my book.

As for what drew me to this topic, I always wanted to know more about materials science from a historical point of view. When I was a materials science professor I occasionally used stories in my class to make lessons more engaging. This book is an exploration of materials science in context, but much more. I believe readers, students, scientists, and professors will enjoy learning about how our inventions fit in the larger cultural fabric. This book offers a bird’s eye view of the impact of materials, but also provides an occasion to think about the innovations on the horizon… I visited a lot of archives: from one-room historical societies in Connecticut to huge halls like the Library of Congress in D.C. I also traveled to England to see the birthplace of penicillin in London as well as read the papers of J. J. Thompson in Cambridge. It is important to visit the location where things happen so that you can “feel” the space. Also, it is important to go to archives because whatever you are looking for is not on Google. Archives don’t often scan their materials. It is important that a researcher turns every page in a collection, as the consummate biographer Robert Caro says, because sometimes you might find something on a small scrap of paper that will send your project in a different direction. Such serendipity happened to me a number of times in the archives… When I was writing, I used an old Mac, which had an ancient operating system that had difficulty reaching the web. This prevented me from going down a Google rabbit hole and forced me to write. I preferred quiet spaces and my cellphone was always on vibrate. If I had a tough time writing, I would set a timer on my computer for 20 minutes. I could always convince myself to write for that long. If I didn’t notice the timer, all the better. I wrote my notes in a fancy notebook, which forced me to be extra neat, since my penmanship is not the greatest. I learned to appreciate index cards, too. They keep key facts and are easier to organize than a computer file. My method is very much a study of old tech. This was what worked for me. Everyone has to find a process that works best for them.

In another interview from last year, Dr. Ramirez described her first introduction to materials science at school:

One day, I was sitting in a class called “Introduction to Materials Science,” where everyone said, “Oh, this class is really, really boring.” I had the same bad attitude about it that everyone else did. But the first day, Professor L. B. Freund blew me away. He said, “The reason we don’t fall through the floor, the reason my sweater is blue, and the reason the lights work all has to do with the interaction of atoms. And if you can understand how they do that, you can make them do new things.”

So here I was, 18 years old, maybe 19 years old, and my mind was completely blown. Because he was absolutely right. In that moment, I started looking at everything and I’m thinking, Yes, that’s because of atoms; yes, that’s because of atoms; yes, that’s because of atoms. … I found the puzzle that was very interesting to me, and I found a way to frame the world… Materials science has been taught many different ways. But when he said that, it resonated with me… here it was a sentence that resonated with me because he essentially gave me a framework to understand everything around me. And that’s what put me on the path to becoming a materials scientist.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)