Thammasat University students interested in political science, ancient history, classical studies, and religion may find a new book useful.

Rome: An Empire of Many Nations: New Perspectives on Ethnic Diversity and Cultural Identity is an Open Access book available for free download at this link.

The Thammasat University Library collection includes several books about different aspects of the Roman Empire.

The Roman Empire was so wide-ranging that some archaeologists have studied objects made in the Mediterranean region that were transported as far as Siam.

As The Bangkok Post reported in 2017,

ROMAN TRACES

A book called Traces of the Roman World in U Thong and Southern Thailand, published last month, reveals further evidence of U Thong’s connection to global empires.

The book contains a collection of studies from German scholar Brigitte Borell who has analysed Roman artefacts found in Thailand.

A bronze lamp from the early Byzantine era, dated to around the fifth or sixth century AD, was found in Kanchanaburi’s historical Pong Tuk site in 1927.

The lamp, around 30cm in height and width, could have been offered as a gift from maritime trade transactions before ending up in the Dvaravati Buddhism complex in Pong Tuk, which is located nearby U Thong, writes Borell.

Another artefact found in U Thong was a coin of Marcus Piavonius Victorinus, a Roman emperor who ruled the Gallic Empire from 260 to 274 AD. The coin was minted during a period modern historians call the “Crisis of the Third Century” in which Romans faced border unrest, plague and economic depression.

Victorinus, a member of an aristocratic family, was proclaimed an emperor by the army but later murdered by one of his officers.

The coin was bought into the collection of Gen Montri Hanwichai before he donated it to the U Thong National Museum in 1966.

The coin, made of silver and alloy, features Victorinus wearing a crown and cuirass. The reverse side shows Salus, the Roman goddess of health and well-being.

Bowell’s study states that large volumes of this coin were minted during Victorinus’s short reign. Coins from other Roman emperors’ reigns were found in Cambodia and Vietnam.

“However, the questions of how and when these coins arrived in Southeast Asia are still difficult to answer,” said Bowell.

“The discovery of a coin of Victorinus at U Thong should not necessarily be seen as evidence for direct or indirect contact with the Mediterranean world in the third century AD. The coins might have been taken to the east only after the currency reforms of Aurelian in AD 274 when new coin types were introduced and debased silver coinage was unsuccessfully demonetised.”

The coin might have arrived as late as the fourth and fifth century, much later than the date when it was minted.

Still, the discovery of the coin indicated that Thailand could have been engaged in powerful, international trade exchanges back in the day.

Part of the Introduction to Rome: An Empire of Many Nations reads:

When Greek historians turned their attention to the Roman Empire, the main question they sought to answer, which they displayed prominently in their introductions, was the reason for the success of the Empire. Success was defined in terms of acquisition, extent, stability and duration of conquest. Polybius, although not the first Greek historian of Rome, was perhaps the first to formulate the question, which he stated like a banner in the introduction to his complex work: his purpose was to explain ‘by what means and under what system of government the Romans succeeded in less than fifty-three years in bringing under their rule almost the whole of the inhabited world, an achievement which is without parallel in human history’. A century later, Dionysius of Halicarnassus did Polybius one better by adding duration of rule to Rome’s achievement: ‘the supremacy of the Romans has far surpassed all those that are recorded from earlier times, not only in the extent of its dominion and in the splendor of its achievements – which no account has as yet worthily celebrated – but also in the length of time during which it has endured down to our day’; and his long preface is filled with other such proclamations. In the second century CE, Appian of Alexandria wrote the same idea in less florid prose: ‘No ruling power up to the present time ever achieved such size and duration’, after stating which he embarked on a long proof. These three historians are representative of a prevailing trend.

Whatever one may think of post-colonialism, its early forerunners and current advocates, its impact as stated has been to encourage attention to the individual (i.e. the identity and inner lives of persons and groups), and in doing so, shake the main impetus of understanding the Roman Empire from the ancient question of ‘success’ in terms of extent and longevity to the human experience of the Empire, and of empire in general. In this, it may prove to be one of the more productive turns in Roman history. The present generation has produced a plethora of studies of identity, ethnicity, multi-cultural structures in the Roman Empire, asking not primarily Why and How but What and Who…The center of gravity in Roman studies has shifted far from the upper echelons of government and administration in Rome or the Emperor’s court to the provinces and the individual. As Veyne noted, ‘in a multinational empire whose makeup was multiple, heterogeneous, unequal, and sometimes hostile and badly integrated, the identity of each individual was inherently complex’. And Greg Woolf, whose work in this area has been both originary and instrumental, notes that the focus of ‘identity politics’ has been ‘not on the emergence of vast imperial identities, but rather on how imperial regimes have shaped local experiences; on the emergence of newly self-conscious peoples and nations; on diasporas and displacements; and on how the experience of migration has impacted on the lives of countless individuals’. Indeed, from the perspective of our own time, this turn in Roman studies reflects the sharpened focus in contemporary politics, education, social relations and legislation on individual identity, ethnicity and the problems of a multi-cultural society. Future generations will decide whether this has in fact added to our knowledge and understanding of the Roman Empire.

Naturally, the turn in Roman studies was preceded by developments in other academic fields, such as the study of ethnic groups and boundaries in anthropology and the dynamics of individual identity against the larger collective, in psychology…

The study of ethnicity and identity in the Roman Empire is more often than not collaborative, given the wide range of languages, territories and specialties required for such a many-faceted topic. The turn toward identity and ethnicity has been the result of both new investigations of the old materials and the greater emphasis placed on other sources: private and local epigraphy, letters and private documents on papyri, local narratives, non-Roman literatures including those in languages other than Greek, regional art.

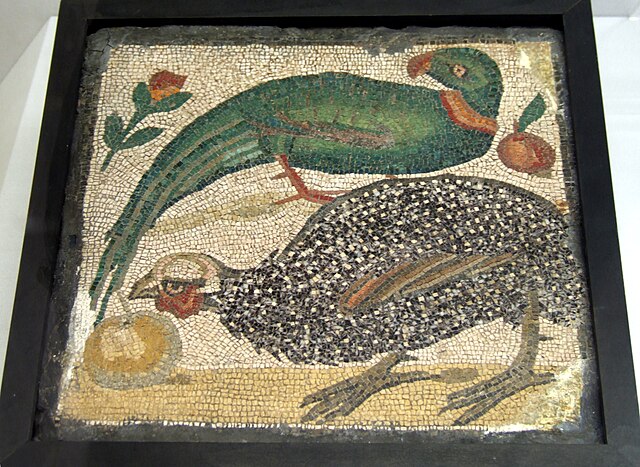

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)