A new Open Access book available for free download at this link may be useful for TU students interested in history, archaeology, architecture, urban studies, political science, and sociology.

A Contemporary Archaeology of London’s Mega Events: From the Great Exhibition to London 2012 is by Dr. Jonathan Gardner, an archaeologist and heritage researcher based at Edinburgh College of Art, Scotland, the United Kingdom.

As defined by the author, mega events may be open for only a few weeks or months, but permanently impact the urban landscape.

The TU Library collection includes many books about different aspects of urban studies.

A Contemporary Archaeology of London’s Mega Events may be downloaded for free at this link.

Mega events may result in city districts being demolished and rebuilt. They attract international participants and their organizers seek to leave an enduring legacy.

In London, these spectacles were long-lived and persistent, rather than transient or short-term. Using an analytical approach inspired by the archaeology of the recent past and present-day, the long-term history of some events are explored.

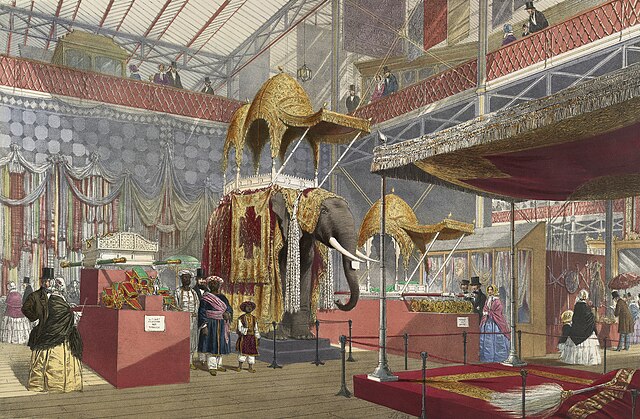

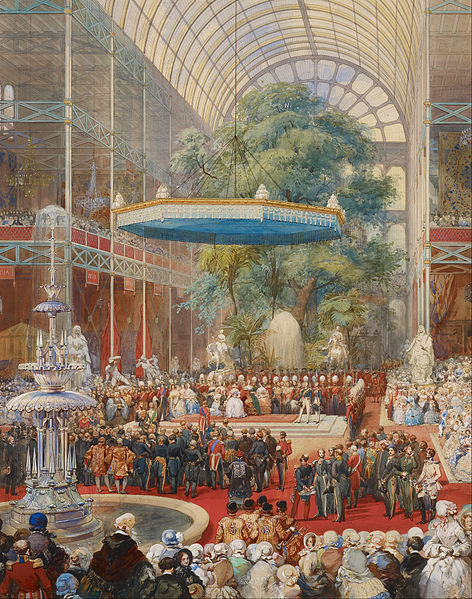

These include the contents and building materials of the 19th century Great Exhibition’s Crystal Palace; how the 1950s Festival of Britain’s South Bank Exhibition used displays of ancient history to construct a new post-war British identity; and how London 2012, as the latest of London’s mega events, dealt with competing visions of the past as archaeology, waste and heritage to create a positive legacy for future generations.

As Mr. Gardner writes,

Although these mega events – the Great Exhibition of 1851, the 1951 South Bank Exhibition of the Festival of Britain and the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games – reshaped the city, they, in turn, were products of London’s history and inextricable from its preexisting social and material environments. Each event assembled an enormous array of ideas, materials and participants from around the world to create new visions of the past, present and future, the effects of which continue to be felt today, despite the years and decades that have passed since they closed. Just what is a mega event though? Although primarily addressing the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century expositions and World’s Fairs, Paul Greenhalgh captures the sense of scale and spectacle common to all mega events: imagine an area the size of a small city centre, bristling with dozens of vast buildings with every conceivable type of commodity and activity known, in the largest possible quantities; surround them with miraculous pieces of engineering technology, with tribes of primitive peoples, reconstructions of ancient and exotic streets, restaurants, theatres, sports stadiums and bandstands. Spare no expense. Invite all nations on earth to take part by sending objects for display and by erecting buildings of their own. After six months, raze this city to the ground and leave nothing behind, save one or two permanent landmarks. Though less dramatic, Maurice Roche helpfully further defines mega events as a genre of very large-scale, globally oriented, peripatetic cultural spectacles that ‘have dramatic character, mass popular appeal and international significance.’ As mid-nineteenth-century products of the Industrial Revolution, mega events emerged as the largest internationally oriented cultural and sporting events the world had ever known, and, by the late twentieth century, had gained their ‘mega’ moniker in recognition of this. Several different varieties of mega event emerged in the aftermath of London’s Great Exhibition of 1851 – widely seen as the world’s first mega event and one of the subjects of this book – but generally speaking, they can be divided into two variants. The first to emerge was the exhibitionary form that dominated the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and encompassing the many different International Exhibitions, Expositions and World’s Fairs. These were then eclipsed by sporting mega events from the mid-twentieth century onwards and, in particular, the large-scale competitions of the FIFA World Cup and the Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games. While Greenhalgh’s description succinctly captures mega events’ vast scale and, with talk of ‘primitive’ people, their early versions’ close connections to imperialism and racism, it does leave one wondering if such spectacles really do ‘leave nothing behind’. I do not dismiss the significance of these ‘permanent landmarks’ (perhaps most famously the Eiffel Tower as a remnant of the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle), but the intent of this book is far more ambitious than an archaeological survey of such leftovers. I instead want to question the idea that mega events simply disappear after they close their doors, and to demonstrate their surprisingly persistent effects upon their host cities and societies.

Although mega events are often seen as showcases of the ‘world of tomorrow’, in this book I show that they have a far broader array of temporal relationships, many of which draw on visions of the past just as much as those of the future. It is this complexity of relationships to time that draws me to these events and that is the reason for this book’s existence. My approach is in response to a tendency by both contemporaries of mega events and some later commentators to see them as dematerialised symbols, representatives or stand-ins for temporal metanarratives. For example, each mega event discussed in this book – the Great Exhibition of 1851, the South Bank Exhibition of the Festival of Britain (1951) and the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games (fig. 1.1) – are often reduced to metonyms for an entire epoch or historical period. The Great Exhibition and 1851 are frequently regarded as the high point of Victorian ebullience and the coming of age of British industrial might and modernity writ large. The year of 1951 and the Festival of Britain are similarly seen as representatives of a post-war, left-wing political settlement and the birth of the Welfare State. More recently, the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games are, even now, viewed nostalgically by some as evidence of a time of national unity, and ‘a relic from another age’, before the division of Brexit, the pandemic and the so-called culture wars. In such accounts, mega events seem to somehow stand outside normal time, worlds apart from the host cities and societies that lie beyond their glass palaces or security fences. While the urge to simplify such events as singularly historic moments or representatives of paradigm shifts is understandable, this risks underselling the complexity and rich materiality of mega events. To challenge this dematerialising tendency, in this book I show how mega events cannot be interpreted in such shortlived terms but, instead, must be seen as having a presence that stretches long before and after their relatively short periods of operation. Mega events are also inextricable from the mass of competing pre-existing temporal relationships that comes with their contents, participants and host sites. As we will see, these relationships are not only spatially and socially laminated upon the neighbourhoods and places in which events take place, but also extend to the distant places from which they draw their components, objects, materials, audiences and workers, and, in turn, to where these different elements are distributed in their aftermath. This book emerged from my own very small part in London’s most recent mega event: my employment as an archaeologist in 2007 and 2008 in Stratford (East London), excavating on the site of the 2012 Games prior to construction. As part of a large team tasked with recording and removing archaeological remains, this experience led me to recognise how mega events’ effects stretch far beyond the weeks or months they were open to the public. I began to think about how those buried artefacts that we so carefully recovered and documented would not only have stayed in the ground, but also about how the future of the site we picked over would have turned out very differently without the coming of the mega event. In Stratford the Games literally reshaped the city and our interpretation of its history. However, this reshaping was not a one-sided relationship; it was only because of Stratford’s long history of land use (and particularly the role of industrialisation) that the 2012 Games came to be hosted here in the first place.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)