Thammasat University students interested in music, European history, cultural studies, German culture, and related subjects may find it interesting to participate in a free book launch on Claiming Wagner for France.

The event is hosted by the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, The University of Melbourne, Australia.

The TU Library collection includes several books about different aspects of the music of the German composer Richard Wagner.

In addition, recordings and DVDs of his music may be listened to at the Puey Ungphakorn Library, Rangsit campus and the Rewat Buddhinan Audiovisual Center, Undeground level 2, Pridi Banomyong Library, Tha Prachan campus.

The speaker will be the author Dr. Rachel Orzech, lecturer in musicology and research fellow at the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music, University of Melbourne, Australia.

The event will be held at 2pm Bangkok time on Thursday, 30 June 2022. Students are cordially invited to register at this link:

https://unimelb.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZcscumsrzgrHdZPzXg8Hl57pdk081fPyUYR

The talk will be introduced by Professor Charles Sowerwine, who teaches history at the University of Melbourne.

For further information or with any questions, please write to

fineartsmusic-er@unimelb.edu.au

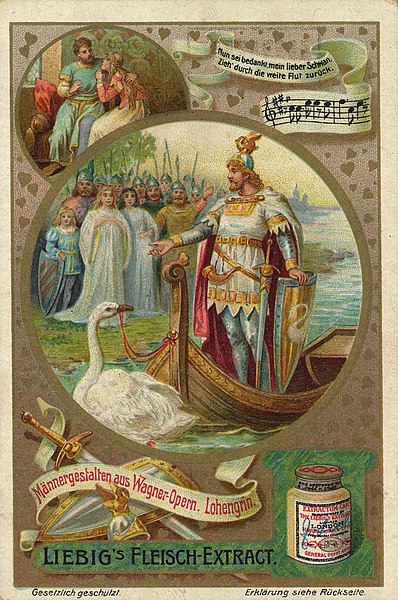

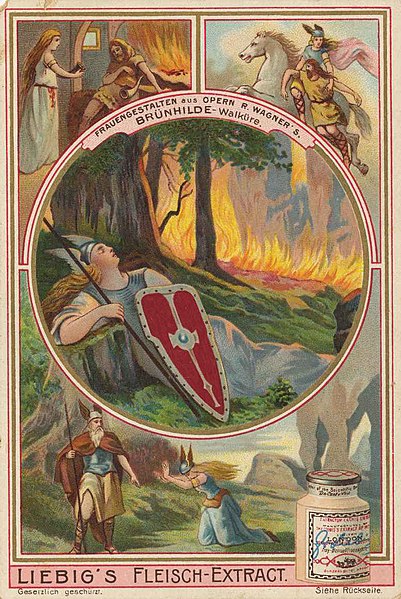

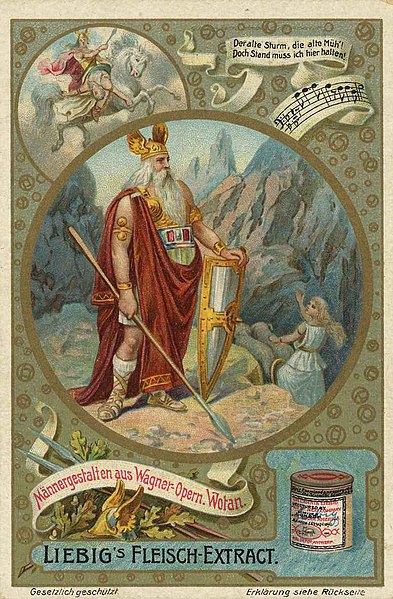

Richard Wagner is mainly remembered for his operas, for which he wrote both the libretto and the music. He saw his operas or music dramas as total works of art that blended poetry, visuals, music, and drama. He considered drama to be more important than music in his operas, although many notable musicians have valued his music highly.

Other listeners have complained that his operas are too long, like the American humorist Mark Twain, who once wrote that Wagner’s music is “not as bad as it sounds.”

Wagner’s four-opera cycle The Ring of the Nibelung has helped inspire many later works, including The Lord of the Rings.

Wagner’s violent hatred of Jews as expressed in his writings foreshadowed the political views of Nazi Germany, that led to genocide of millions of people. Although Wagner was no longer alive when the Holocaust occurred, some historians claimed he might have approved of it.

As the publisher’s description of the book notes,

Richard Wagner was a polarizing figure in France from the time that he first entered French musical life in the mid nineteenth century. Critics employed him to symbolize everything from democratic revolution to authoritarian antisemitism. During periods of Franco-German conflict, such as the Franco-Prussian War and World War I, Wagner was associated in France with German nationalism and chauvinism. This association has led to the assumption that, with the advent of the Third Reich, the French once again rejected Wagner.

Drawing on hundreds of press sources and employing close readings, this book seeks to explain a paradox: as the German threat grew more tangible from 1933, the Parisian press insisted on seeing in Wagner a universality that transcended his Germanness. Repudiating the notion that Wagner stood for Germany, Parisian critics attempted to reclaim his role in their own national history and imagination.

Claiming Wagner for France: Music and Politics in the Parisian Press, 1933-1944 reveals how the concept of a universal Wagner, which was used to challenge the Nazis in the 1930s, was transformed into the infamous collaborationist rhetoric promoted by the Vichy government and exploited by the Nazis between 1940 and 1944. Rachel Orzech’s study offers a close examination of Wagner’s place in France’s cultural landscape at this time, contributing to our understanding of how the French grappled with one of the most challenging periods in their history.

One of the many paradoxes of Wagner appreciation is due to the fact that even though some composers of classical music have been unpleasant, Wagner is notorious for having been one of the most unpleasant personalities ever to produce great music.

He hated the French people, but somehow his music was nevertheless made popular in France, even despite two world wars in which France and Germany were adversaries.

As Dr. Orzech writes,

In the midst of war in 1915, composer and music critic Gustave Samazeuilh wrote a letter to the short-lived journal La Musique pendant la guerre, applauding its editors’ initiative and regretting that his wartime responsibilities did not allow him to contribute. He then turned to recent calls to ban German (and specifically Wagner’s) music, a move which he opposed: Even in these tragic times, your journal will not have played a negligible role if it has managed both to warn against the regrettable excesses of a facile, supposedly patriotic overreach with regard to the masterpieces of deceased geniuses—masterpieces capable of surviving the most violent conflicts—and above all to inspire in our theaters and concert halls a concern with widening their repertoire and emphasizing the richness, strength, and variety of our French contemporary school. Samazeuilh’s wartime characterization of Wagner’s music dramas as masterpieces “capable of surviving the most violent conflicts” foreshadows the Wagner criticism he published over the next three decades, justifying Wagner’s music as a force that transcended conflict and politics by virtue of its universality. The persistence in his writings of this theme of universality over a period spanning two world wars points to the central argument in this book: that the Occupation-era discourse that positioned Wagner as a vehicle for Franco-German collaboration did not constitute a rupture with earlier Wagner reception in Paris. Rather, it was rooted in Wagner discourses developed previously, depicting Wagner as emblematic of universality and Franco-German rapprochement, as well as an object of both fear and attraction. By a great irony of history, the concept of a universal Wagner that had been used to resist the Nazis in the 1930s was transformed into the infamous collaborationist rhetoric promoted by the Vichy government and exploited by the Nazis between 1940 and 1944. Samazeuilh displayed a particular talent for seamlessly shifting and adapting his Wagner commentary to suit changing political exigencies… In previous decades, French critics had used Wagner to symbolize a diverse array of political arguments and positions, from right-wing nationalism to left-wing humanism and egalitarianism. In the 1930s, however, the Parisian press depicted him as transcending such divisions and holding universal appeal. Wagner had stood in for German nationalism and chauvinism in earlier periods of Franco-German conflict, which has led to the erroneous assumption that the French rejected him as relations with Germany grew more hostile with the advent of the Third Reich. On the contrary, this book argues, in the 1930s Parisians repudiated the notion that Wagner stood for Germany, attempting to reclaim his role in their own national history and imagination. Even once war was declared in 1939 and a ban on the performance of Wagner’s music was implemented, commentators insisted that it was simply a temporary measure designed to avoid public disturbance. They maintained that “music has no borders” and that art and politics should not be mixed. Then came the invasion of Paris by German troops and the beginning of the Occupation. The drastically new political situation demanded new discourses, and the discourse of Wagner’s universality was transformed into one that depicted him as a vehicle for Franco-German collaboration.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)