Thammasat University students interested in music, education, the history of science and technology, transportation, infrastructure, and related subjects may find a new book useful.

Railways & Music is an Open Access book available for free download at this link:

https://directory.doabooks.org/handle/20.500.12854/78417

The TU Library collection includes a number of books about different aspects of the history and development of railways.

The book by the English music historian Julia Winterson begins:

This is the first book to give a comprehensive coverage of music connected with the railways. In the nineteenth century, thousands of miles of railway lines transformed time, space and distance. Across Europe composers celebrated with music such as waltzes and polkas, cantatas, piano pieces and saucy music hall songs. Moving into the twentieth century, iconic twentieth-century works, such as Britten’s Night Mail and Honegger’s Pacific 231, captured the sounds of locomotives. Railways and trains are so deeply ingrained in the popular imagination that they feature in hundreds, possibly thousands, of popular songs. In North America, early railroad songs told of hoboes, heroes, villains, and train wrecks and the sounds of the railroad were heard in boogie-woogie, blues, gospel, jazz, and rock music. In total, this book describes over 50 pieces of classical music and covers more than 250 popular songs…So what is the appeal which has attracted so many musicians? Is it the relationship with time where the train moving through the landscape speaks of the physical and metaphorical power of the railway to connect people and places? Or is it simply the attraction of the evocative sounds, the roaring and wheezing of the steam train, the shriek of the whistle and the clattering track rhythms that are so easily recognisable and adaptable to change? Perhaps composers are in part attracted by the parallels between a train journey and a composition. Both have a beginning, middle and an end and take place across time. It is not difficult to see how the sometimes laboured departure of a steam engine can be performed as a slow introduction, building up to a quicker development, then slowing down to a halt as the passengers reach the end of their journey. It is an easy model for composers to follow and there are many examples of this blueprint to be found from the ‘The little train of the Caipira’ by Villa-Lobos to Duke Ellington’s ‘Daybreak Express’… The railway had an effect on many aspects of society; it stimulated economic development and had the capacity to change people’s lives. In Europe the railway could act as a significant tool in nation building; and for some countries it was an important instrument of military strategy. Across Europe, the opening of new lines was celebrated in music including two of the most well-known railway pieces, the famous Railway Pleasure Waltzes by Johann Strauss I which was composed in advance of the much anticipated 1837 opening of the line between Floridsdorf and Deutsch Wagram in Austria, and Hans Christian Lumbye’s Copenhagen Steam Railway Galop, written to celebrate the opening of the line from Copenhagen to Roskilde. For some time the train was seen as the epitome of modernity. In the early twentieth century the Futurist movement sought to express this in mechanical imagery. One of the most well-known orchestral train pieces, Arthur Honegger’s Pacific 231, was created in this spirit, evoking raw power and inexorable machine-driven motion. As the twentieth century moved on, this perception of modernity eventually faded and instead steam trains were sometimes used a symbol of nostalgia in, for example, the Kinks’ song ‘Last of the steam-powered trains’ where the train acts as a metaphor for the past.

There are many other examples of songs where the train is used as a metaphor, an obvious example being ‘Morningtown ride’ by The Seekers which uses a train journey as a metaphor for sleeping. In spirituals and gospel music a railroad trip is often used to represent the journey through life with heaven as its final destination, some songs such as ‘Life’s railway to Heaven’ include a warning that any departure from righteousness would lead elsewhere. There is much to be learnt from the lyrics of train songs. Train journeys are a common theme, often linked to notions of connection and isolation: songs about the first train and the last train; leaving and coming home; and separating lovers and bringing them back together again. In some ways lyrics can act as social documents which capture historical experience, whether it be the humorous songs about the railway found in British music hall which look at life from a working-class perspective, or the voice of resistance heard in work songs and the blues which share aspects of the black experience. Some songs embody political values and others are overtly political, not least Hugh Masekela’s powerful song ‘Coal train’ with its grim documentation of the trains that transported migrant workers to and from the gold mines in South Africa. The book reveals some interesting insights into the relationship between the musicians and the railways. The Italian composer Rossini hated trains. This was probably a reaction to a catastrophic train journey from Antwerp to Brussels in 1836 where he was so unnerved by the experience that he fainted, was ill for several days afterwards and swore that he would never set foot on a train again. Nevertheless this did not prevent him from writing A little train of pleasure. Similarly, the composer Percy Grainger wrote Train Music as a response to a journey in ‘a very jerky train going from Genova to San Remo’. Those musicians who loved trains, however, are to be found more frequently amongst the composers and songwriters featured in this book. When Benjamin Britten was working on Night Mail, he enjoyed spending evenings at Harrow station listening to the trains arriving and departing… Several composers used the train as a sanctuary and a place to compose when on tour; Duke Ellington rented his own Pullman train car so that he would have a place to eat and sleep when touring in segregated towns. The American Charles Ives enjoyed his two-hour daily commute and it was one of these journeys which inspired his piece ‘From Hanover Square North, at the end of a tragic day, the voices of the people again arose’ recalling his experience of communal singing at the station the day that the news broke of the sinking of the RMS Lusitania. In all the book describes over 50 pieces of classical music and covers over 250 songs, recordings of all of these can be found on the internet. Given the huge number of pieces of train music, particularly songs, it has, of course, been impossible to write about each of them. Some of these have been captured by title only with several pages of lists of classical pieces, jazz numbers and popular songs. There are also, of course, many instances of railways and music that can be found in film and television, enough to fill another book in fact, but these have not been included.

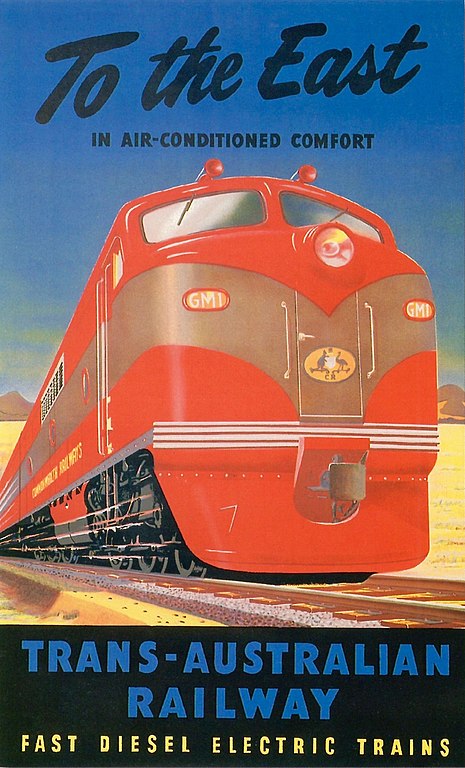

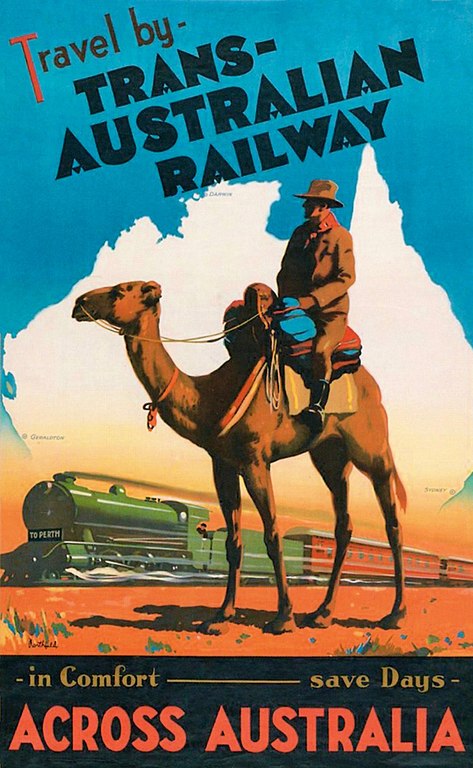

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)