Thammasat University students interested in sociology, political science, history, economics, and related subjects may find a new book useful.

Demographic and Family Transition in Southeast Asia is an Open Access book available for free download at this link:

https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/54418

The TU Library collection includes a number of books about different aspects of demographic trends in Southeast Asia.

The book’s author is Professor Wei-Jun Jean Yeung, a Taiwanese sociologist and demographer who teaches at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore.

Her book offers trends and patterns of demographic and family changes in eleven Southeast Asian nations over the past 50 years. Historical, cultural and policy background are provided as context for family changes in Southeast Asia.

Data on marriage rates, age at marriage, incidence of singlehood, cohabitation, and divorce is examined as well as fertility rates, age at childbearing, and childlessness. In addition, household sizes, and incidence of one-person households, single-parent families, as well as extended and composite households are presented in terms of the well-being of children and young people.

For example, singlehood rates at ages 30–34 have risen sharply in Southeast Asia, with Singapore having the highest proportion of women who remain single at ages 30–34, followed by Thailand, Brunei, and Myanmar.

The age at marriage has been rising universally. Fertility rates started to decline more rapidly in Southeast Asia from the 1970s to the end of the 1990s. Total fertility rate (TFR) or the average number of children that a woman might have varies considerably, with 1.2 in Singapore and 1.5 in Thailand to about 3 each in the Philippines and Lao PDR and 5.6 in Timor-Leste.

Southeast Asia has experienced some of the most rapid fertility declines to replacement-level fertility, or near-replacement-level fertility, ever recorded. Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam fit into this category; Indonesia and Myanmar are not far behind.

In Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia, and Vietnam, there has been an increase in the number of extended families over the past decade despite economic growth, which is likely due to the ageing trend.

Throughout Southeast Asia female educational enrolment rates have rapidly risen in all countries, due to lower fertility and delayed marriage.

Here are some other observations by Professor Yeung:

- Most Southeast Asian countries are starting to age gradually. However, in Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, the proportion of 65-year-olds and above, as well as the oldest old (aged 80 and above), are rising exponentially. In 2015, the old-age dependency ratio in Singapore and Thailand were 16.1 and 14.6, respectively, higher than the world average of 12.6.

- Conversely, the child dependency ratio in the region has been declining, though the population remains relatively young. The majority of the countries have child dependency ratios that are higher than the world average of 39.7…

- Poverty incidence has generally declined in the region. Significant reductions in poverty levels were seen in Vietnam, Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Thailand where the poverty headcount ratios were cut by about 35–75% within fifteen years. Timor-Leste, on the other hand, experienced increased poverty rates from 36.3% in 2001 to 41.8% in 2014.

- Singapore and Thailand have the largest proportion of highly educated people, with Singapore having around 90% and Thailand with 50% of their population obtaining tertiary education. In contrast, Lao PDR has the least number of people going to the tertiary level with just a 17% enrolment rate in 2015, and Malaysia has seen a decline in tertiary enrolment from 37% in 2010 to 29% in 2015.

- Women’s participation in paid labour has been high in Southeast Asia, but increased engagement of women in paid work was more pronounced in Brunei and Singapore. Meanwhile, the opposite trend was observed in Thailand and Timor-Leste.

- Marked changes have occurred in the family formation behaviour of the population in Southeast Asia. Comparing with the 1970s, marriage rates seem to have risen in the region except in Timor-Leste. But when comparing with the 1980s and the 1990s, significantly fewer Thais, Singaporeans, and Bruneians are getting married nowadays. On the other hand, more Indonesians and Filipinos are tying the knot.

- Generally, those who get married tend to do so at a later age. Notable exceptions are Indonesia, Vietnam, and Cambodia where the singulated mean ages at marriage (SMAM) have recently gone down. A significantly higher number of women and men in their late 30s are also remaining single particularly in Myanmar, Singapore, and Thailand.

- Available data show divorce rates are increasing in Singapore, Thailand, and Brunei, but decreasing in Indonesia and Vietnam.

- Consensual unions or cohabitations also warrant attention, particularly in the Philippines and Thailand where 20–40% of women 20–24 years old and more than 10% of men 25–29 years old are cohabiting…

- Childlessness is now higher in Cambodia and Indonesia and has escalated by 16% in Singapore since the 1970s. On the other hand, Thailand and Vietnam have fewer childless women in the same age group…

- Extended family households remain pervasive in Southeast Asia with most countries having more than 25% of this type of household. In Indonesia and Malaysia, extended households are decreasing but in Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia, and Vietnam, the percentages are increasing.

- Single-parent households, which are less than 8% of households in each of the countries, are generally decreasing except in Thailand and the Philippines. This downward trend is similarly observed for composite households which are less common than single-parent households.

- Tertiary enrolment rates in the region are generally converging to reach gender parity. Nevertheless, female enrolment rates in tertiary education are consistently higher than that for males in half of the countries in the region, namely Brunei, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand, and the Philippines.

- Overweight—The prevalence of overweight children is growing, especially in Thailand and Indonesia having the highest rates of 11% in 2014. WHO defines overweight for children under five years of age as weight-for-height greater than two standard deviations above WHO Child Growth Standard median. Globally, there is also a shift of trend from high-income countries to rising numbers in low- and middle-income countries, most commonly seen in urban settings (World Health Organization, 2018). Lindsay et al. (2017) found that the rapid economic growth in Southeast Asian countries has contributed to the increasing number of overweight children, particularly in urban areas. The situation is phenomenal in all countries except for Myanmar and Cambodia. Indonesia, with the highest rate of increase, also accounted for the most number of overweight children at 11.5% in 2015. As Fig. 7.2 shows, the number of overweight children in Indonesia drastically increased from 2000 at 1.5% to 12.3% in 2010, and then it dropped slightly to 11.5% in 2013. Indonesia is followed by Thailand at 10.9% and Brunei Darussalam at 8.3% in 2009. In Thailand, it gradually rose by 9.6 percentage points (from 1.3% in 1987 to 10.9% in 2012) in 25 years. Indonesia spent only 10 years, as compared to 25 years for Thailand for the similar range of increase in overweight children. The remaining countries grew at a steady rate. Research shows that factors such as overweight mothers before pregnancy, high birthweight of children, higher than the required portion of food taken by children, and consumption of high caloric food contribute to childhood obesity in Thailand and Indonesia.

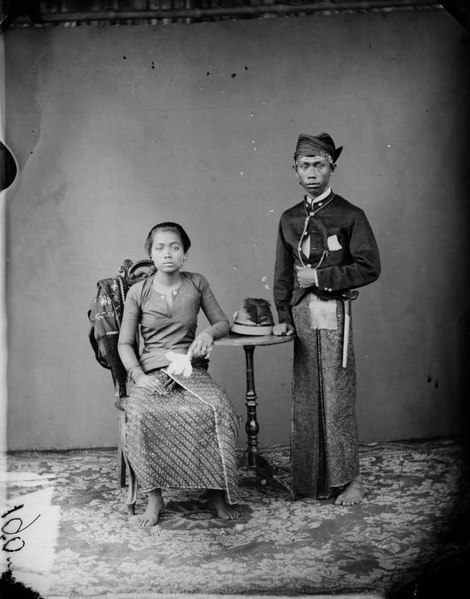

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)