Thammasat University students who are interested in political science, government, gender studies, sociology, Asian studies, and related subjects may find a newly available book useful.

Substantive Representation of Women in Asian Parliaments is an Open Access book, available for free download at this link:

https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/57617

The TU Library collection includes several books about different aspects of gender equality in politics.

The publisher’s description of Substantive Representation of Women in Asian Parliaments follows:

Combining data from nearly 100 interviews with national parliamentarians from ten Asian countries, the contributors to this book analyze and evaluate the advancement of gender equality in Asia. As of the year 2022, no country in Asia has gender parity in its parliament. Meanwhile, the proportion of national-level women parliamentarians in Asia averages a mere 20%. What is more important than simple descriptive representation, however, is whether outcomes for women are improving. Rather than focusing on numerical representation, the chapters in this book focus on the substantive representation of women. In other words, what do women and men parliamentarians do to advance women’s well-being and gender equality? Using semi-structured interviews, the author of each chapter examines these efforts in the context of a specific Asian country. The case studies include Bangladesh, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Nepal, the Philippines, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, and Timor-Leste. The book is an essential resource for scholars and students of Asian politics and the politics of gender.

The book begins:

This book presents the results of a pioneering new large-scale study on how national parliamentarians in Asia are advancing women’s substantive representation and gender equality. As the world’s largest continent, home to three-fifths of the world’s population, Asia is critical to advancing global gender equality which will require, among other things, better representation of women at the parliamentary level. As this book reveals, there is considerable diversity across Asia when it comes to women’s substantive representation. Most promisingly, our study finds that younger generations of women (and men) are more actively working to advance gender equality than many older parliamentarians in the region. However, some members of parliament (MPs) clearly exhibit much greater motivation and dedication to representing women than others. Also, we find that formal and informal institutions such as parliamentary committee structures, gender quotas, and political party rules play a significant role in determining to what extent such representation takes place. This study departs from previous analyses of women’s numerical or descriptive representation in parliament which has long been a focus of comparative studies of women in Asian parliaments. Following the work of Hanna Pitkin, the

descriptive representation of women (DRW) in parliament refers to whether the legislature is like a “ ‘mirror’ of the nation” in terms of “being something rather than doing something.” In other words, DRW refers to whether the composition of the parliament’s members reflects the composition of society in its descriptive attributes. This means that since women comprise about half of the resident or citizen population in most countries, roughly half of the parliamentarians should also be women. As of the year 2022, however, no country in Asia has achieved this. Currently, the proportion of national-level women parliamentarians in Asia averages a mere 20% with some countries such as Sri Lanka (5%) having very few women at all while others like Taiwan (42%) are higher but still below parity. Instead of focusing on DRW, this study focuses on substantive representation of women (SRW). As Pitkin (1967) explains, substantive representation concerns how representatives act for a particular constituency or cause. The key issue is not how many women are MPs, but what do women (and men) parliamentarians do to advance women’s well-being and gender equality…

If it is the case (as would seem quite plausible) that women are generally more dedicated (than men) to improving women’s well-being and gender equality, then we would expect to observe a positive correlation between DRW and SRW. This would mean that if a greater number of parliamentarians (and other important political decision-makers) are women, then the laws and policies of a government should correspondingly be more beneficial to women. Likewise, the procedures by which a government functions and the content of its agenda would become more women-friendly. Phillips (1995) famously referred to this dynamic as the “politics of presence.” Relatedly, the “critical mass” theory holds that when women parliamentarians exceed a certain membership threshold (often seen as about 30%), SRW should significantly improve because the resulting change in group proportions shifts women from being mere “tokens” or a small minority to comprising a large minority. In this spirit, the 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action issued by the United Nations’ Fourth World Conference on Women declared

that women should comprise a minimum share of 30% on all important political decision-making bodies globally including national parliaments.

Addressing the question of whether a greater proportion of women in parliament really has much impact on public policy, an influential study by Schwindt, Bayer and Mishler concluded, “The percentage of women in the legislature is a principal determinant of women’s policy responsiveness and of women’s confidence in the legislative process.” More recently, Celis and Erzeel have noted that many academic studies have indeed found women in politics more active in acting for women compared to men. Similarly, among Asian countries, a recent study by Tam found that in Singapore, women members of parliament (WMPs) asked more questions in parliament on women’s rights and traditional women’s concerns than male members of parliament (MMPs). In India, WMPs were likewise more active in speaking up in parliamentary debates on behalf of women and children compared to MMPs. A recent study of legislative bill sponsorship over the past two decades in South Korea and Taiwan has also clearly demonstrated that “female legislators are substantially more likely to focus on women’s issues compared to male legislators.”…

Outside the parliament, civil society and social movements play an important role in pressuring the state to change its laws. Moreover, cross-national research finds that strong, autonomous feminist organizations together with feminist mobilizations and movements contribute significantly in the march toward progressive policy changes because they generate social knowledge about women’s positions in society, challenge traditional gender roles, and prioritize gender issues. For instance in Malaysia, women’s political participation increased after its 1999 general elections when the “Women’s Agenda for Change” manifesto was issued and a Women’s Candidacy Initiative sought to increase the number of women MPs.

Conversely, certain civil society forces such as religious organizations have strongly opposed women’s empowerment in some countries. Likewise, the presence of an informal “old boys” network in government can be a major obstacle to SRW. Another mediating factor is the role of mass media depending on whether it serves as an open public forum, as a critical watchdog, or simply as a mouthpiece for the government. Media messages can both directly and indirectly support a culture of gender equality and persuade or dissuade women from believing they have the ability to govern as political leaders.

Longer-term and international forces also make a difference in influencing who has agenda setting, preference shaping, and decision-making power. Norms promoted by international organizations can support gender equality. The socioeconomic development of a country across agrarian, industrial, and post-industrial stages may also strongly influence attitudes and reforms in favor of gender equality by increasing women’s access to tertiary education and employment in those professional occupations that often serve as pipelines into politics.

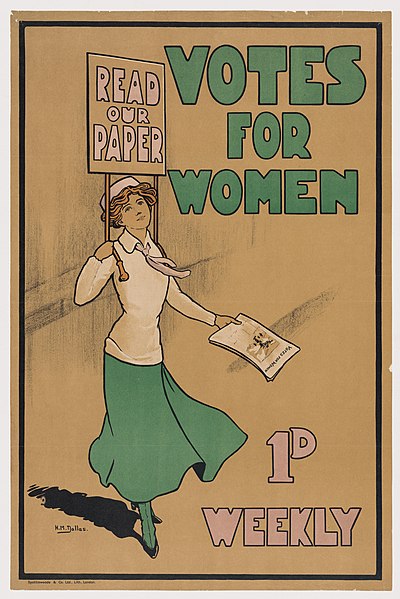

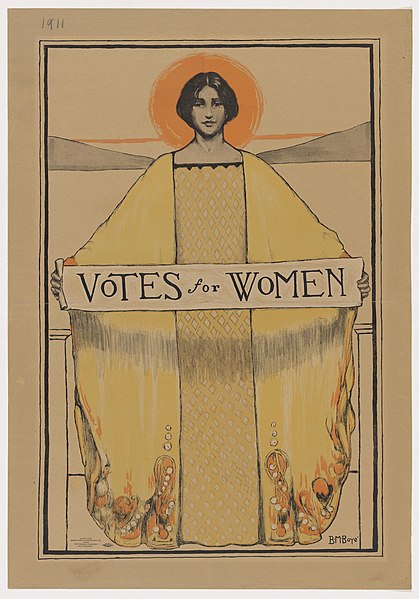

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)