The Thammasat University Library has acquired a new book that should be useful for students interested in history, sociology, literature, folklore, myth, medieval studies, and related fields.

Scotland’s Merlin: A Medieval Legend and its Dark Age Origins is by Dr. Tim Clarkson, a medieval historian.

The TU Library collection also includes other books about medieval legends.

Merlin is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on historic and legendary figures, was introduced by the 12th-century British author Geoffrey of Monmouth.

Geoffrey’s version of the character became immediately popular, especially in Wales. Later writers in France and elsewhere expanded the account to produce a fuller image, creating one of the most important figures in the imagination and literature of the Middle Ages.

Merlin’s traditional biography casts him as having supernatural powers and abilities, including prophecy and shapeshifting. Merlin grows up to be a sage and serves as King Arthur’s advisor and mentor, making a series of prophecies about future events.

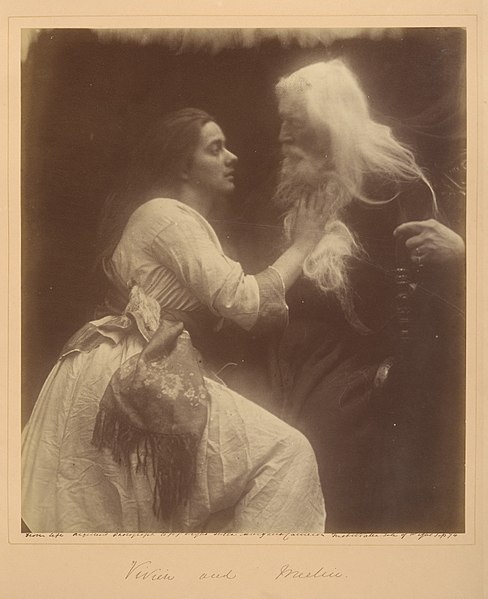

One French story describes Merlin as being bewitched and killed by his student known as the Lady of the Lake. Other texts describe his retirement and death.

Dr. Clarkson investigates whether Merlin existed as a historical figure by asking when the legend of Merlin began and what its historical roots may be. He traces Merlin back to a historical figure who lived in sixth-century Scotland.

According to the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, Merlin was

the famous bard of Welsh tradition, and enchanter of Arthurian romance. His history as related in this latter may be summarized as follows. The infernal powers, aghast at the blow to their influence dealt by the Incarnation, determine to counteract it, if possible, by the birth of an Antichrist, the offspring of a woman and a devil. As in the book of Job, a special family is singled out as subjects of the diabolic experiment, their property is destroyed, one after the other perishes miserably, till one daughter, who has placed herself under the special protection of the Church, is left alone. The demon takes advantage of an unguarded moment of despair, and Merlin is engendered. Thanks, however, to the prompt action of the mother’s confessor, Blayse, in at once baptizing the child of this abnormal birth, the mother truly protesting that she has had intercourse with no man, Merlin is claimed for Christianity, but remains dowered with demoniac powers of insight and prophecy. An infant in arms, he saves his mother’s life and confounds her accusers by his knowledge of their family secrets. Meanwhile Vortigern, king of the Britons, is in despair at the failure of his efforts to build a tower in a certain spot; however high it may be reared in a day, it falls again during the night. He consults his diviners, who tell him that the foundations must be watered with the blood of a child who has never had a father; the king accordingly sends messengers through the land in search of such a prodigy. They come to the city where Merlin and his mother dwell at the moment when the boy is cast out from the companionship of the other lads on the ground that he has had no father. The messengers take him to the king, and on the way he astonishes them by certain prophecies which are fulfilled to their knowledge. Arrived in Vortigern’s presence, he at once announces that he is aware alike of the fate destined for him and of the reason, hidden from the magicians, of the fall of the tower. It is built over a lake, and beneath the waters of the lake in a subterranean cavern lie two dragons, a white and a red; when they turn over the tower falls. The lake is drained, the correctness of the statement proved, and Merlin’s position as court prophet assured. Henceforward he acts as adviser to Vortigern’s successors, the princes Ambrosius and Uther (subsequently Uther-Pendragon). As a monument to the Britons fallen on Salisbury Plain he brings from Ireland, by magic means, the stones now forming Stonehenge. He aids Uther in his passion for Yguerne, wife to the duke of Cornwall, by Merlin’s spells Uther assumes the form of the husband, and on the night of the duke’s death Arthur is engendered. At his birth the child is committed to Merlin’s care, and by him given to Antor, who brings him up as his own son. […]

Some years ago the late Mr Ward of the British Museum drew attention to certain passages in the life of St Kentigern, relating his dealings with a “possessed ” being, a dweller in the woods, named Lailoken, and pointed out the practical identity of the adventures of that personage and those assigned by Geoffrey to Merlin in the Vita; the text given by Mr Ward states that some people identified Lailoken with Merlin. Ferd. Lot, in an examination of the sources of the Vita Merlini, has pointed out the more original character of the “Lailoken” fragments, and decides that Geoffrey knew the Scottish tradition and utilized it for his Vita. He also comes to the conclusion that the Welsh Merlin poems, with the possible exception of the Dialogue between Merlin and Taliessin, are posterior to, and inspired by, Geoffrey’s work. So far the researches of scholars appear to point to the result that the legend of Merlin, as we know it, is of complex growth, combined from traditions of independent and widely differing origin. Most probably there is a certain substratum of fact beneath all; there may have been, there very probably was, a bard and soothsayer of that name, and it is by no means improbable that curious stories were told of his origin. It is worth noting that Layamon, whose translation of Wace’s Brut is of so much interest, on account of the variants he introduces into the text, gives a much more favourable form of the “Birth” story; the father is a glorious and supernatural being, who appears to the mother in her dreams. Layamon lived on the Welsh border, and the possibility of his variants being drawn from genuine British tradition is general] recognized. The poem relating a dialogue between Merlin and, his brother bard, Taliessin, may also derive from genuine tradition. Further than this we can hardly venture to go; the probability is that anything more told of the character and career of Merlin rests upon the imaginative powers and faculty of combination of Geoffrey of Monmouth.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)