Through the generosity of the late Professor Benedict Anderson and Ajarn Charnvit Kasetsiri, the Thammasat University Library has newly acquired some important books of interest for students of Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) studies, political science, literature, and related fields.

They are part of a special bequest of over 2800 books from the personal scholarly library of Professor Benedict Anderson at Cornell University, in addition to the previous donation of books from the library of Professor Anderson at his home in Bangkok. These newly available items will be on the TU Library shelves for the benefit of our students and ajarns. They are shelved in the Charnvit Kasetsiri Room of the Pridi Banomyong Library, Tha Prachan campus.

Among them is a newly acquired book that should be useful to TU students who are interested in Italy, literature, cultural history, comparative religion, allied health sciences, and related subjects.

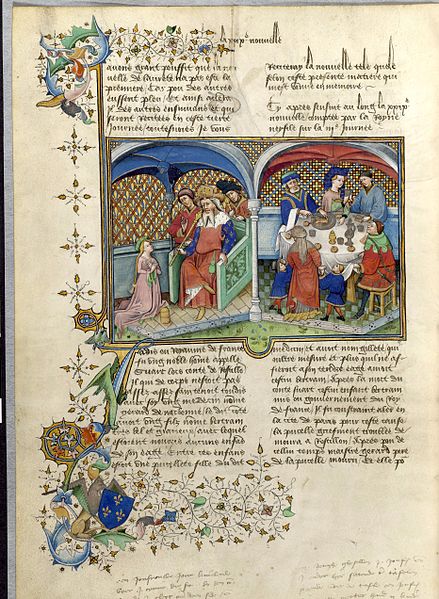

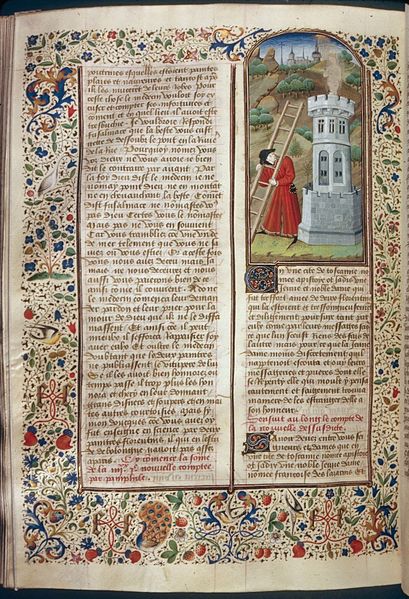

The Decameron is a collection of short stories by the Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio, written in the 1300s.

Boccaccio was a poet and humanist. The book contains 100 tales told by a group of seven young women and three young men; they are sheltering in a house outside Florence, Italy to escape the Black Death, a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. The Black Death, was the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causing the deaths of an estimated 75 to 200 million people. Boccaccio probably started writing the Decameron after the epidemic of 1348, and completed it by 1353. Tales of love in The Decameron are sometimes tragic but also humorous. In addition to its literary value and widespread influence, for example on Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, The Decameron offers a document of life at the time.

The title Decameron derives from two Greek terms meaning a ten-day event, referring to the schedule during which the characters of the story tell their tales.

The TU Library collection contains a number of books by and about Boccaccio and his work.

One writer, the American translator Nathan Haskell Dole, explained about Boccaccio’s style:

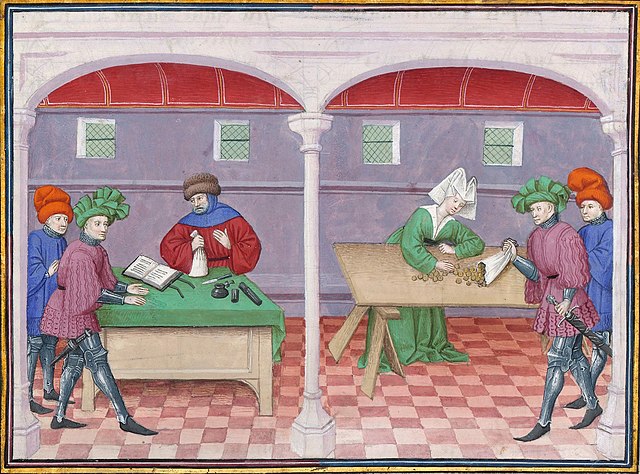

The Italians of the fourteenth century had a more dignified mode of society entertainment.

The ladies and gentlemen that gathered in the salon of the court or in the shady garden organised what they called una lieta brigata, a happy jolly, merry, jocund band and appointed a captain or it might be, a queen who should give them a theme and call upon one after another of the company to illustrate it with stories. Such themes as “The magnanimity of princes,” “Concerning those that have been fortunate in love,” “Sudden changes from prosperity to misfortune,” “The guiles that women have practised on their husbands” and the like were common.

This was the origin of the so-called novella.

Symonds says:

“The novella is invariably brief and sketchy. It does not aim at presenting a detailed picture

of human life within certain artistically chosen limitations, but confines itself to a striking

situation or tells an anecdote illustrative of some moral quality.”

He goes on to show how the fact that these novelle were either read aloud or improvised on the spur of the occasion “determined the length and ruled the mechanism” of them. “It was impossible,” he says, “within the short space of a spoken tale to attempt any minute analysis of character or to weave the meshes of a complicated plot. The narrator went straight to his object, which was to arrest the attention, gratify the sensual instincts or stir the tender emotions of his audience by some fantastic, extraordinary, voluptuous, comic or pathetic incident. He sketches his personages with a few swift touches, set forth with pungent brevity and expends his force upon the painting of their central motive.”

All of this is set forth with much care in the second chapter of his ” Renaissance in Italy, ” where he explains further that the sole object of the novella was entertainment and where he illustrates how its success was obtained in new strange incidents, in obscenity veiled or repulsively naked, in gross or graceful jests, in practical jokes and delicate pathos, often by “elaborate rhetorical development of the main emotions, placing carefully studied speeches in the mouth of heroine or hero and using every artifice for appealing directly to the feelings of his hearers.’*

Human nature seems not to have changed since the first known calendar was computed, that is to say in July 4241 B.C. The coarse and animal, which is to a certain extent inseparable from man as a featherless biped, still has its more or less powerful attraction. It is found in all literatures and has to be reckoned with. The tales of the Thousand and One Nights have to be expurgated for ordinary reading and there are few of the Cento Novelle that would do now to present to a mixed company. In studying any past literature we must expect shocks to our conventionalities.

Here are some observations from The Decameron:

- A sin that’s hidden is half forgiven.

First Day, Introduction

- Wrongs committed in the distant past are far easier to condemn than to rectify.

Second Day, Fifth Story

- People are more inclined to believe in bad intentions than in good ones.

Third Day, Sixth Story

- Do as we say, not as we do.

Third Day, Seventh Story

- In the affairs of this world, poverty alone attracts no envy.

Fourth Day, Introduction

- He who is wicked and held to be good, can cheat because no one imagines he would.

Fourth Day, Second Story

- They banish us to the kitchen, there to tell stories to the cat.

Fifth Day, Tenth Story

- The nature of wit is such that its bite must be like that of a sheep rather than a dog, for if it were to bite the listener like a dog, it would no longer be wit but abuse.

Sixth Day, Third Story

- An oak is not felled by a single blow of the axe.

Seventh Day, Ninth Story

- The power of the pen is far greater than those people suppose who have not proved it by experience.

Eighth Day, Seventh Story

And about Boccaccio:

There are few works which have had an equal influence on literature with the Decameron of Boccaccio. Even in England its effects were powerful. From it Chaucer adopted the notion of the frame in which he has enclosed his tales, and the general manner of his stories, while in some instances, as we have seen, he has merely versified the novels of the Italian. In 1566, William Paynter printed many of Boccaccio’s stories in English, in his work called the Palace of Pleasure. The first translation contained sixty novels, and it was soon followed by another volume, comprehending thirty-four additional tales. These are the pages of which Shakespeare made so much use. From Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, we learn that one of the great amusements of our ancestors was reading Boccaccio aloud, an entertainment of which the effects were speedily visible in the literature of the country.

- John Colin Dunlop, The History of Fiction

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)