Thammasat University students who are interested in literature, British studies, Germany, history, sociology, literary criticism, philosophy, comparative literature, literary theory, romantic poetics, creative critical writing, and related subjects may find a newly available book useful.

Shelley with Benjamin: A critical mosaic is an Open Access book, available for free download at this link:

https://directory.doabooks.org/handle/20.500.12854/97661

Its author is Dr. Mathelinda Nabugodi, a Research Associate in the Literary and Artistic Archive at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge University, the United Kingdom.

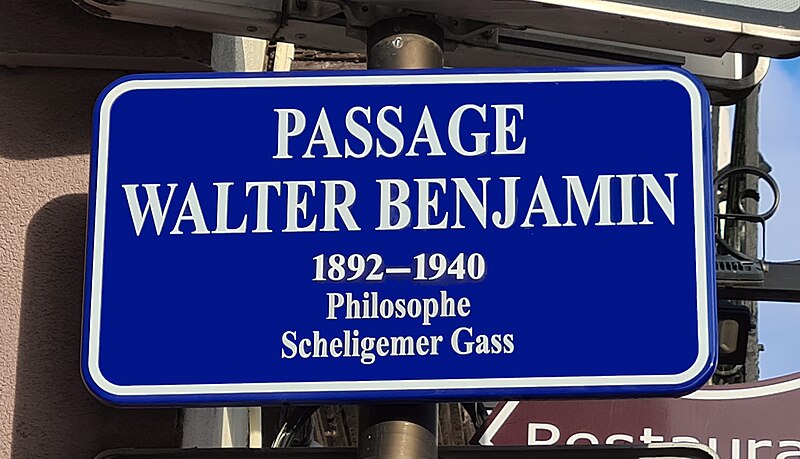

Percy Bysshe Shelley was one of the major English Romantic poets of the early 1800s. Walter Benjamin was a German philosopher and cultural critic.

The TU Library collection includes other books by and about Shelley and Benjamin.

The publisher’s description of the book explains:

Shelley with Benjamin: A critical mosaic is an experiment in comparative reading. Born a century apart, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Walter Benjamin are separated by time, language, temperament and genre – one a Romantic poet known for his revolutionary politics and delicate lyricism, the other a melancholy intellectual who pioneered a dialectical method of thinking in constellations. Yet, as the above montage of citations from their works demonstrates, their ideas are mutually illuminating: the mosaic is but one of several images that both use to describe how literature lives on through practices of citation, translation and critical commentary. In a series of close readings that are by turns playful, erotic and violent, Mathelinda Nabugodi unveils affinities between two writers whose works are simultaneously interventions in literary history and blueprints for an emancipated future. In addition to offering fresh interpretations of both major and minor writings, she elucidates the personal and ethical stakes of literary criticism.

In a preface, Dr. Nabugodi notes:

A split can also be observed in the two writers who are the subjects of this book: Percy Bysshe Shelley and Walter Benjamin. The first is a British Romantic poet, born in 1792 to a baronetcy, expelled from university ‘for contumaciously refusing to answer questions . . . and for also repeatedly declining to disavow a publication titled The Necessity of Atheism’, yet nonetheless destined to become one of the most canonical poets in the English language.1 The second is a German Jewish philosopher born exactly a hundred years later, in 1892, into a solidly bourgeois family in Berlin, who was effectively expelled from the academy after his habilitation thesis was deemed incomprehensible. The work was later published as The Origin of German Tragic Drama and contributed to making Benjamin one of the most influential critical theorists of the twentieth century. Both were read in their lifetimes but died failures – or they believed. My engagement with their writings opens with a meditation on afterlife that grounds my reading in their own reflections about how literary works live on beyond the author’s death.

Here are some thoughts by Shelley from books, some of which are in the TU Library collection:

You would not easily guess

All the modes of distress

Which torture the tenants of earth;

And the various evils,

Which like so many devils,

Attend the poor souls from their birth.

- “Verses On A Cat” (1800)

Chameleons feed on light and air:

Poets’ food is love and fame.

- An Exhortation (1819)

Fame is love disguised.

- An Exhortation (1819)

Hell is a city much like London —

A populous and smoky city.

- Peter Bell the Third (1819)

Have you not heard

When a man marries, dies, or turns Hindoo,

His best friends hear no more of him?

- Letter to Maria Gisborne (1820)

Music, when soft voices die,

Vibrates in the memory —

Odours, when sweet violets sicken,

Live within the sense they quicken.

Rose leaves, when the rose is dead,

Are heaped for the beloved’s bed;

And so thy thoughts, when thou art gone,

Love itself shall slumber on.

- Music, When Soft Voices Die (1821)

The world’s great age begins anew,

The golden years return,

The earth doth like a snake renew

Her winter weeds outworn;

Heaven smiles, and faiths and empires gleam,

Like wrecks of a dissolving dream.

- Hellas (1821)

Poetry is the record of the best and happiest moments of the happiest and best minds.

- A Defence of Poetry (1821)

And about Shelley:

Shelley appealed to me from his hatred of tyranny. And also from his very vivid sense of beauty, natural beauty, and every kind of beauty. And I thought he sort of portrayed a lovely world of the imagination.

- Bertrand Russell, Interview (1962)

Some thoughts by Walter Benjamin:

Of all the ways of acquiring books, writing them oneself is regarded as the most praiseworthy method. … Writers are really people who write books not because they are poor, but because they are dissatisfied with the books which they could buy but do not like.

- Unpacking my Library: A Talk About Book Collecting (1931)

The question to address is that of the conscious unity of student life … the will to submit to a principle, to identify completely with an idea. The concept of “science” or scholarly discipline serves primarily to conceal a deep-rooted bourgeois indifference. […] The true sign of decadence is not the collusion of the university and the state (something that is by no means incompatible with honest barbarity), but the theory and guarantee of academic freedom, when in reality people assume with brutal simplicity that the aim of study is to steer its disciples to a socially conceived individuality.

- The Life of Students (1915)

A religion may be discerned in capitalism—that is to say, capitalism serves essentially to allay the same anxieties, torments, and disturbances to which the so-called religions offered answers.

- Capitalism as Religion (1921)

The art of storytelling is reaching its end because the epic side of truth, wisdom, is dying out. […] If sleep is the apogee of physical relaxation, boredom is the apogee of mental relaxation. Boredom is the dream bird that hatches the egg of experience.

- “The Storyteller” (1936)

To articulate what is past does not mean to recognize “how it really was.” It means to take control of a memory, as it flashes in a moment of danger. For historical materialism it is a question of holding fast to a picture of the past, just as if it had unexpectedly thrust itself, in a moment of danger, on the historical subject. The danger threatens the stock of tradition as much as its recipients. For both it is one and the same: handing itself over as the tool of the ruling classes. […] There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. […] The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the “state of emergency” in which we live is not the exception but the rule.

- Theses on the Philosophy of History (1940)

Only a thoughtless observer can deny that correspondences come into play between the world of modern technology and the archaic symbol-world of mythology.

- Arcades Project (1927-1940)

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)