The Thammasat University Library has acquired a new book that should be useful for students interested in political science, history, linguistics, Chinese studies, sociology, and related fields.

China’s Great Liberal of the 20th Century — Hu Shih: Founder of Modern Chinese Language is by Mark O’Neill, an author and journalist living in Hong Kong.

The TU Library collection has many other books about different aspects of the Chinese language.

The TU Library also owns another book containing research by Mr. O’Neill.

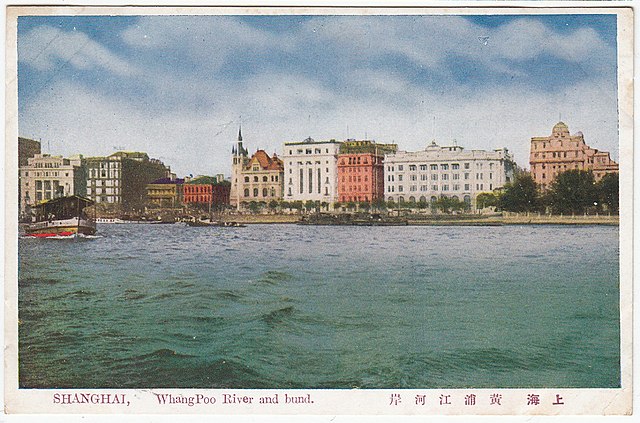

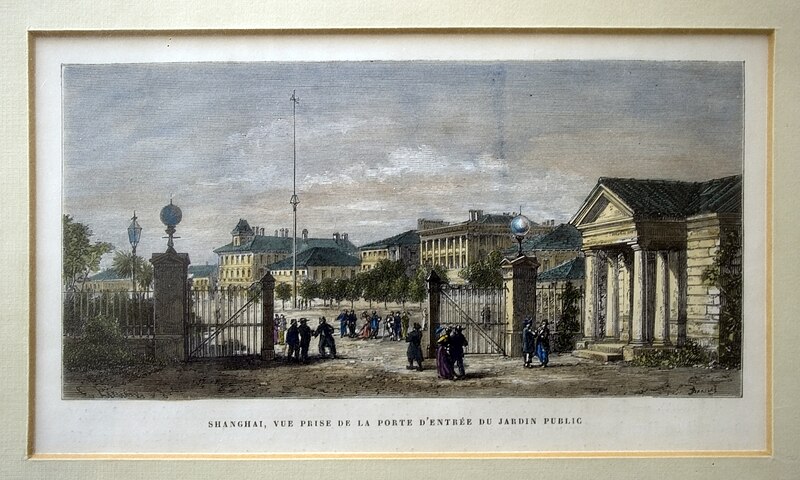

Hu Shih was a Chinese diplomat, essayist, literary scholar, philosopher, and politician born in Shanghai. Hu is widely recognized today as a key contributor to Chinese liberalism and language reform in his advocacy for the use of written vernacular Chinese. He had a wide range of interests such as literature, philosophy, history, textual criticism, and pedagogy.

As one Open Access book available for free download about Hu’s political writings notes,

It is worthwhile to point out that Hu Shih’s profound understanding of Chinese and American cultures derived not only from his crosscultural educational background (he was an undergraduate student at Cornell University from 1910 to 1914 and a graduate student at Columbia University from 1914 to 1917), but also from his direct involvement in the building of a modern Chinese culture, and his participation in American and Chinese discussions in international politics. His dual identity as a scholar and a statesman, a philosopher and an ambassador, a pragmaticist and an idealist, put him in a unique position to observe the changes in China and its relation to the world over the course of the twentieth century. Aside from Hu Shih’s achievement as an eminent scholar and public figure, one can also see in his writings the spiritual struggle of a leading Chinese scholar who lived, worked, and was exiled in the United States for a total of twenty-six years and seven months. As soon as he left China for America to pursue his bachelor’s degree in 1910, Hu Shih embarked upon a search for a new identity and destiny as one of the first Chinese students sent to the United States for modern education under the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program. In 1937, Hu Shih was sent by the Nationalist government as a special envoy to Washington, DC, to seek the United States’ help and support in China’s “Resistance War” against Japan, and a year later, in 1938, he was appointed as the Chinese ambassador to the United States, serving as the main liaison between the Chinese government and the United States. After he finished his term as ambassador, he continued to live in New York for four years, during which time he was a Chinese delegate to the United Nations Conference on International Organization (aka the San Francisco Conference) and the Conference of the Establishment of UNESCO in 1945. During his stay in the United States, Hu Shih also lectured at many American universities and research institutes, including Harvard. In July 1946, after living in the United States for nine years, Hu Shih returned to China and soon witnessed the drastic ascendancy of the Chinese Communist Party. He chose exile in America, where he spent the next nine years of his life, from 1949 to 1958. In April 1958, he moved to Taiwan to take up the position of president of Academia Sinica, and died in Taipei in February 1962. After he left China for America in 1949, Hu Shih did not return to his homeland ever again. In Hu Shih’s English-language political writings, which were mostly written during his exile in the United States, one can see a tormented soul concealed in rational words, and his occasional disappointment wrapped in seemingly optimistic narrative. Readers of this book will thus gain a balanced and subtle view of Hu Shih, not only as a prominent scholar and public figure, but also as a human being with passion, anxiety, and courage, whose concern for the future of China was as strong as his love for his family and friends who were left in China during his exile in America. […]

In “Do We Need or Want Dictatorship?,” as another example, Hu Shih considered whether authoritarianism or dictatorship was necessary for China to achieve prosperity and solidarity. In this article, he engaged in a debate with scholars and government officials who advocated a strong centralized government in China led by powerful dictators, akin to Joseph Stalin and Benito Mussolini. Although Hu Shih maintained that it was absolutely unnecessary for the Chinese people to embrace the idea of a dictator and an authoritarian social system, he did not rule out the consideration of some form of “modern dictatorship” or “enlightened despotism” as an option for governing China. He also did not fundamentally dismiss the concept of a “modern dictatorship,” which he argued was theoretically more sophisticated and advanced than an elementary-level democracy:

Great Britain and the United States are both homes of democracy; and the very fact that government by experts (or by a “Brain Trust”) has made its appearance only in recent years is concrete proof that democracy is but an elementary form of government, and that modern dictatorship, which calls for highly developed technical skill in its execution, belongs really to the politics of the most advanced seminary.

It must be clarified that Hu Shih was not rooting for authoritarian rule or government. He was simply trying to figure out what the best form of government was for China and for humankind as a whole in different social and historical contexts. He rebuked any uncritical acceptance of political theories, agendas, or systems. “It must be pointed out,” Hu Shih stressed, “that modern dictatorship is not dependent on the wisdom of the leader alone— although strong leadership is of primary importance—but on the numerous technical experts around him.”20 In other words, what Hu Shih sought to highlight in the concept of “modern dictatorship” was the technical aspect of modernization rather than the idea of a highly centralized government. An effective government was one that made good use of the modern techniques of science rather than relying on the judgment or power of a singular leader or oligarchical group; an ideal government should be run collectively by a group of legal representatives of the people who are equally responsible for the wealth and growth of the nation.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)