Thammasat University students who are interested in art, sociology, gender studies, popular literature, feminism, and related subjects may find a newly available book useful.

Sugar, Spice, and the Not So Nice: Comics Picturing Girlhood is an Open Access book, available for free download at this link:

https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/61392

It is edited by Dr. Dona Pursall and Dr. Eva Van de Wiele, who teach in the Department of Literary Studies of Ghent University, Belgium.

The TU Library collection includes other books about different aspects of girlhood.

An article about relevant research at the Ohio State University, the United States of America, observes:

Not all strong females challenging gender roles in the comics were superheroes like Captain Marvel or Wonder Woman.

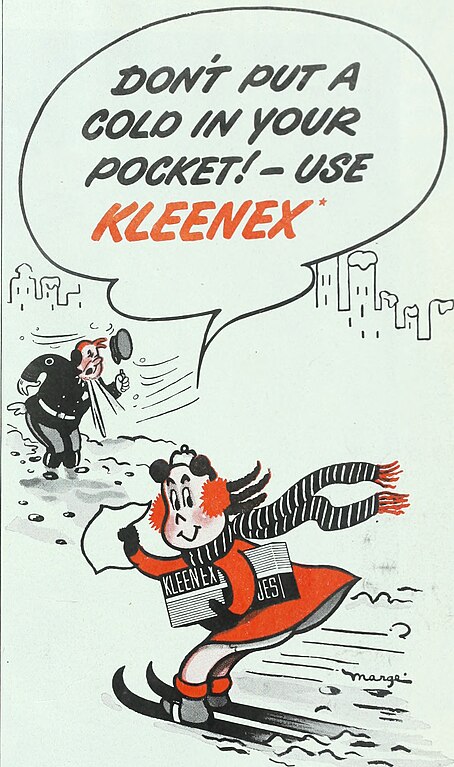

Some were just regular girls with a bit of attitude and names like Little Iodine, Little Lulu and, yes, Nancy. And at least one—Li’l Tomboy—pushed the boundary of what girls could do in comics even further.

In her new book Funny Girls: Guffaws, Guts and Gender in Classic American Comics, author Michelle Ann Abate examines the groundbreaking and overlooked role that young girl protagonists played in classic comics during the first half of the 20th century.

“Girls like Li’l Tomboy were not superheroes in the conventional sense, like Wonder Woman, but they did have heroic qualities,” said Abate, professor of literature for children and young adults at The Ohio State University.

“They were spirited, outspoken and strong. They affirm the existence of strong female protagonists during the Golden Age of comic books.”

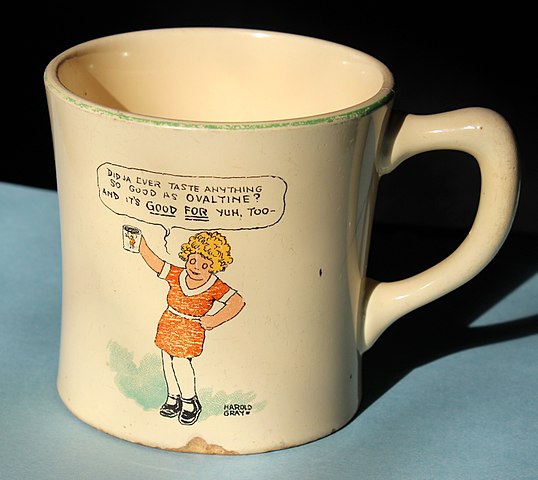

Some of the classic girl characters, like Nancy and Little Orphan Annie, are still well known today. But it is easy to overlook how groundbreaking these comics were at the time, Abate said.

“We tend to frame the current explosion of female characters in the comics as a new thing, but it is part of a longer tradition,” she said.

“There have been strong female protagonists in comics from the beginning.”

The earliest girls in comics, like Little Orphan Annie, which debuted in 1924, did show some spunkiness that challenged the gender roles of the time. But they also didn’t stray too far from societal norms, according to Abate.

Little Orphan Annie stood up for herself, fought when necessary and talked back to adults on occasion. However, she also relied on Daddy Warbucks to rescue her when things got out of hand.

“She was independent and capable and resilient, to a point. But Daddy Warbucks was still there as a backup,” Abate said.

“The same was true for other girls in the comics, like Nancy. She was sassy, but was still within the confines and structures of white, middle-class suburban families.”

One theme in many of the early comics featuring girls was the names: Li’l and Little were often added, from Little Orphan Annie to Little Lulu, Little Audrey and Little Iodine.

“Her name might be Iodine, but she was still little, cute and adorable. The diminutive added to the name made them less threatening,” she said.

But if there was one girl in the comics of the time who added at least the hint of threat, that may have been Li’l Tomboy, according to Abate.

“People remember Nancy and Little Orphan Annie. I think Li’l Tomboy was that gem that most people haven’t heard of, but maybe was the most interesting one of the whole group,” she said.

Released in October 1956, Li’l Tomboy was published for three years, featuring a character who didn’t act like an average white, middle-class girl in this postwar period. She had a conventionally feminine appearance, but her behavior did not match her frilly clothes.

As her name implies, 5-year-old Li’l Tomboy wasn’t doing what girls in the 1950s generally did. She didn’t like dolls, got into frequent fistfights and enjoyed playing football with the boys.

Li’l Tomboy’s unconventional behavior went beyond just acting “like a boy.”

“She was a juvenile delinquent, to be honest. She trespasses, commits petty theft, throws a rock through a window and talks back to police officers. It goes beyond being naughty,” Abate said.

Li’l Tomboy used being a cute, white, feminine, middle-class girl to her advantage. She was with a boy when she threw a rock through a window—noting that he would be blamed and not her. […]

Abate said the female characters in comics of this time sent a message to the boys and girls who read them.

“They said that girls can be just as feisty and strong and fun and mischievous as boys can,” she said.

The publisher’s description of the book notes:

Sugar, Spice, and the Not So Nice offers an innovative, wide-ranging and geographically diverse book-length treatment of girlhood in comics. The various contributing authors and artists provide novel insights into established themes within comics studies, children’s comics, graphic medicine and comics by and about refugees and marginalised ethnic or cultural groups. The book enriches traditional historical, narratological and aesthetic approaches to studying girlhood in comics with practice-based research, discussion and conversation. This re-examination of girls, gender and identity in comics connects with contemporary discourse on gender identity politics. Through examples from both within Europe, the anglophone world and beyond, and including visual essays alongside critical theory, the volume furthermore engages with new developments in contemporary comics scholarship. It will therefore appeal to students and scholars of childhood studies, comics scholars and creators, and those interested in addressing gender identity through the prism of comics.

The book’s introduction states:

The personal experience of girlhood is unique. […] The diversity represented in this collection offers a beginning, a first consideration of how comics’ expression and liberty can and does (or does not) celebrate individuality. In such a project, it is informative to consider unique examples not as exceptions, but rather as typical examples of subjective identity. With this in mind, this introduction lays out some of the central tensions related to girlhood through specific examples. We contemplate the implications of “child” identity constructed in tension with “adult”, explore how “girl” as a term is weighted with roles and categories, and ponder how embodied action and activity is flavoured by social ethics and expectations. This introduction uses comics to study judgements about normative behaviour and aesthetics of girlhood and what this means for how we view departures or exceptions as beyond or outside the constructed ‘girl’.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)