Thammasat University students interested in Asian literature, poetry, China, history, sociology, and related subjects may find a new book useful.

The Poetry of Li He is an Open Access book available for free download at this link:

https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781501504716/html

The Thammasat University Library collection includes several books about different aspects of Chinese poetry.

Li He, who lived around 1400 years ago, was a Chinese poet of the mid-Tang dynasty.

He was described as being very thin, with a unibrow, and long fingernails.

Li He worked as a low-ranking, impoverished official, and died in his late twenties.

He had hoped to take the literary examinations required for a better official career, but he was prevented from doing so by authorities who were jealous of his poetic talent, according to some researchers.

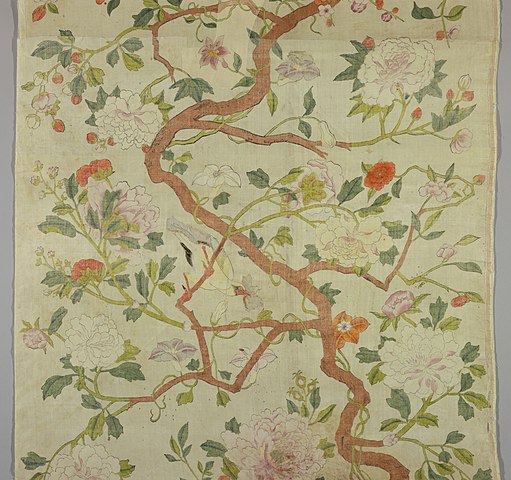

One biographer described him as working hard at his poetry, carrying an old brocade bag with him, and jotting down verses when he thought of them. After he returned home, he arranged these verses into a poem.

His poems were often about ghosts and other supernatural and fantastic themes, winning the nickname of devilish talent or Poetry Devil.

Li He was among the Tang poets most admired by Mao Zedong, the dictator who was also an amateur poet.

This new edition is translated by Associate Professor Robert Ashmore, who teaches at the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures, University of California, Berkeley, the United States of America.

Professor Ashmore notes in an introduction:

From his own lifetime to the present, Li He790–816) has persistently struck readers as an anomalous figure: preternaturally gifted, yet thwarted in his dearest ambitions, he created an inimitable and magnetic brand of poetic writing that won the devotion of generations of readers, but that has also seemed bizarre or even perverse to many. His works’ compelling intensity often seems in direct proportion to an obscurity verging on the hermetic. Later readers’ sense, moreover, of his style, manner, and career became inextricably intertwined with an awareness of his eventual fate: an early reputation as a precocious talent, and ensuing patronage by some of the most influential figures of the era, led in Li He’s case only to a frustrating few years in a dead-end low-level posting at the capital, followed by several further years of futile wandering in pursuit of an alternate career path in the provinces. In the end he returned home, in failing health, and died at twenty-seven, a forlorn figure, leaving behind his mother and one or more siblings.1 We appear to have been exceedingly lucky in that we possess roughly the same number of Li He’s poems as were in circulation shortly after his death. Yet from the earliest times, his works have seemed haunting, orphaned fragments of an incomparable yet incomplete talent.

Here are some examples of poems by Li He:

*

The Last of the Willow-floss

The weeping willow’s leaves grow tough, as orioles feed their broods;

the last of the willow-floss nearly gone, the yellow bees go home.

A dark-tressed youth and a gold-hairpinned wanderer:

in their jug of cerulean glass sink depths of liquid amber.

At the flowery terrace, dusk draws near as springtime takes its leave;

fallen petals rise and dance in the eddying wind.

The elm-pods urge us on, in numbers beyond counting:

Master Shen’s green coins lie strewn along the road to town.

*

To Show to my Younger Brother

My parting from you, brother, is now three years ago;

since my return it’s a bit more than a day.

Green brew of Ling: the wine we share tonight;

pale yellow wrappers: the books from when I left.

These sick bones somehow continue living –

what possibility does this world not contain?

Don’t bother to ask whether it’s an ox or a horse –

make your toss and let “owl” or “black” fall as they will.

*

Seventh Night

The shore of parting on this day is dark;

within the gauze curtain, midnight sorrow.

The magpie takes leave of this moonlight for needle-threading;

flowers enter the loft for airing robes.

In heaven is divided a metal mirror;

the human realm gazes up at the jade hook.

Little Su of Qiantang

once more faces a year’s autumn.

*

Passing by Huaqing Palace

In spring moonlight, crows caw at night;

palace curtains enfold imperial flowers.

As clouds thicken, vermilion window-grilles grow dark;

across fractured stones, purple coins of lichen slant.

Jade bowls still hold remnant dew-drops;

silver sconces glimmer on old silk netting.

Of that Prince of Shu there is no recent news;

beside the spring appear shoots of water-celery.

*

The Young Aristocrat’s “Song of Night’s Close”

Sinuous wisps of aloeswood smoke;

crows cry in the pale light of night’s end.

Along the twisting pool, ripples among the lotuses;

the waist-encircling white jade grows cold.

*

Dream of Heaven

Old Hare and cold Toad weep the sheen of sky;

cloud towers half-open, walls of slanting white.

A jade wheel presses dew, wetting a disc of light;

Simurgh pendants meet on an osmanthus-scented path.

Yellow dust and clear water beneath the three mountains,

a thousand years transposed to the swiftness of a horse’s gallop.

Gazing from afar at the Qi domains – nine spots of smoke;

one trickle of ocean water poured out into a cup.

*

Third Month

The east wind comes: it’s spring as far as the eye can see;

by the flower-filled city willows grow dark, sadder than one can bear.

Through the tiered palace’s deep halls stirs wind from the bamboo grove;

the dancers’ tunics of fresh halcyon are clear as water.

Light and wind spread basil scent beyond a hundred li

warm fogs harry the clouds, dabbing sky and earth.

Palace entertainers in martial costume, eyebrows lightly traced,

wave and sway their brocade banners, warming the double-walled avenue.

Along winding waters the scent flows off, never to return,

as pear flowers fall completely away to leave an autumnal garden.

*

Fourth Month

Dawns are cool, evenings cool, the trees like carriage-canopies;

lush green of a thousand peaks appears beyond the clouds.

Amid faint fragrant rains, a shimmer of blue-green;

unctuous leaves and coiling flowers blaze bright by the lane’s gate.

In the languid waters of the golden pond sway emerald ripples;

the sun’s maturer rays now ponderous, no more sudden flights.

Unseen, tattered pink and wasted calyx are now estranged.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)