The Thammasat University Library has acquired a new book that should be useful for students interested in film, American cultural studies, history, media studies, and related subjects.

Citizen Welles: A Biography of Orson Welles is by Professor Frank Brady, who teaches communication arts and journalism in the Department of Mass Communications, Journalism, Television and Film at St. John’s University, New York, the United States of America.

The TU Library collection includes other books about different aspects of the life and work of Orson Welles.

Orson Welles was an American actor and director whose career had an international impact.

An article in the Journal of the Siam Society from 2021 about Prisna (ปริศนา), a Thai novel written by Princess Vibhavadi Rangsit in the 1940s and set a decade earlier, notes about the author:

“Chancham loved small, well-timed interjections, and she was prone to them if she thought she could improve upon a story. Orson Welles’ famous improvisation in The Third Man was one of her favorites.”

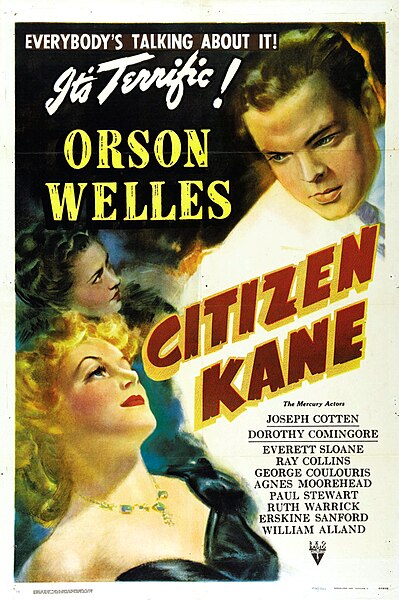

Orson Welles, who had starred in Shakespeare productions in Europe when he was still a teenager and ran theatrical companies in his early twenties, directed the famous film Citizen Kane when he was 25.

In his early thirties, he was cast in the role of a criminal, Harry Lime, in a British film shot in Vienna, The Third Man.

Welles arrived on set at the last possible minute, because according to the film’s director, With Orson you know, everything has to be a drama.

In a well-remembered scene, Welles as Harry Lime the criminal suggests that societies which are peaceful are boring, while places where there is much violence can be creative.

This idea was added to the script by Welles himself.

Welles/Lime says:

You know what the fellow said — in Italy, for 30 years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, they had 500 years of democracy and peace — and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock!

According to film historians, 32 takes were necessary to preserve this speech. The screenwriter, noted novelist Graham Greene, admitted that Welles, and not he, had written these lines. However the film’s assistant director was certain that Welles had heard the general concept somewhere, and did not invent it himself.

As it happens, although the speech has been widely admired by film fans, it is not considered accurate culturally or historically.

After the film The Third Man was released, Swiss moviegoers observed that cuckoo clocks have never been made in Switzerland. Instead, they have been manufactured in the Black Forest, Bavaria, Germany.

And during the time of the Borgias, Switzerland had one of the most feared military forces in Europe, so the concept of Swiss neutrality is also a relative matter.

Regardless of historical accuracy, The Third Man remains worth seeing, like other films by and with Orson Welles.

Here are some observations by Welles about his life and art:

If you want a happy ending, that depends, of course, on where you stop your story.

- From the published screenplay for “The Big Brass Ring” (1987)

I have always been more interested in experiment, than in accomplishment…I don’t take art as seriously as politics.

- From an interview (1960)

I try to be a Christian…I don’t pray really, because I don’t want to bore God.

- Quoted in Citizen Welles: A Biography of Orson Welles

I think I made essentially a mistake in staying in movies but it’s a mistake I can’t regret because it’s like saying I shouldn’t have stayed married to that woman but I did because I love her. I would have been more successful if I hadn’t been married to her, you know. I would have been more successful if I’d left movies immediately, stayed in the theatre, gone into politics, written, anything. I’ve wasted a greater part of my life looking for money and trying to get along, trying to make my work from this terribly expensive paintbox which is a movie. And I’ve spent too much energy on things that have nothing to do with making a movie. It’s about two percent movie-making and ninety-eight percent hustling. It’s no way to spend a life.

- Interview in The Orson Welles Story (1982)

Hollywood is Hollywood. There’s nothing you can say about it that isn’t true, good or bad. And if you get into it, you have no right to be bitter — you’re the one who sat down, and joined the game…The people who’ve done well within the [Hollywood] system are the people whose instincts, whose desires [are in natural alignment with those of the producers] — who want to make the kind of movies that producers want to produce. People who don’t succeed — people who’ve had long, bad times; like [Jean] Renoir, for example, who I think was the best director, ever — are the people who didn’t want to make the kind of pictures that producers want to make. Producers didn’t want to make a Renoir picture, even if it was a success.

- Interview in The Orson Welles Story (1982)

My father once told me that the art of receiving a compliment is, of all things, the sign of a civilized man. He died soon afterwards, leaving my education in this important matter sadly incomplete; I’m only glad that, on this, the occasion of the rarest compliment he ever could have dreamed of, that he isn’t here to see his son so publicly at a loss.

In receiving a compliment, or in trying to, the words are all worn out by now. They’re polluted by ham and corn. And, when you try to scratch around for some new ones, it’s just an exercise in empty cleverness.

What I feel this evening, is not very clever. it’s the very opposite of emptiness… No, if there’s any excuse for us it all, it’s that we’re simply following the old American tradition of the maverick, and we are a vanishing breed. This honor I can only accept in the name of all the mavericks.

And also, as a tribute to the generosity of all the rest of you; to the givers, to the ones with fixed addresses. A maverick may go his own way but he doesn’t think that it’s the only way, or ever claim that it’s the best one, except maybe for himself. And don’t imagine that this raggle-taggle gypsy-o is claiming to be free. It’s just that some of the necessities to which I am a slave are different from yours.

As a director, for instance, I pay myself out of my acting jobs. I use my own work to subsidize my work (in other words I’m crazy). But not crazy enough to pretend to be free. But it’s a fact that many of the films you’ve seen tonight could never have been made otherwise. Or, if otherwise, well, they might have been better, but certainly they wouldn’t have been mine.

The truth is I don’t believe that this great evening would ever have brightened my life if it wasn’t for this: my own, particular, contrariety. Let us raise our cups, then, standing as some of us do on opposite ends of the river, to what really matters to us all: to our crazy, beloved profession, to the movies — to good movies, to every possible kind.

- Speech given upon his acceptance of the American Film Institute Lifetime Achievement award.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)