Through the generosity of the late Professor Benedict Anderson and Ajarn Charnvit Kasetsiri, the Thammasat University Library has newly acquired some important books of interest for students of Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) studies, political science, sociology, and related fields.

They are part of a special bequest of over 2800 books from the personal scholarly library of Professor Benedict Anderson at Cornell University, in addition to the previous donation of books from the library of Professor Anderson at his home in Bangkok. These newly available items will be on the TU Library shelves for the benefit of our students and ajarns. They are shelved in the Charnvit Kasetsiri Room of the Pridi Banomyong Library, Tha Prachan campus.

Among them is a newly acquired book that should be useful to TU students who are interested in philosophy, political science, literature, history, cultural studies, gender studies, and related fields.

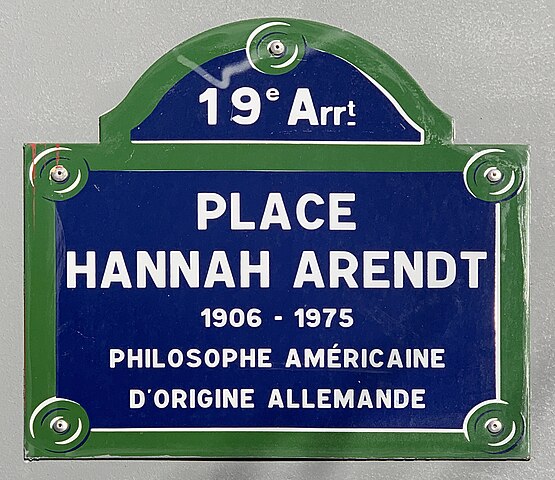

The Human Condition by Hannah Arendt is a book by a German-born American historian and political philosopher.

The TU Library collection includes several other books by and about Hannah Arendt.

She was one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century.

Her works cover a wide range of topics, but she is best known for those dealing with the nature of power and evil, as well as politics, direct democracy, authority, and totalitarianism.

She was born in Linden in the Province of Hanover, Kingdom of Prussia, the German Empire and fled Fascist Europe for America in 1941.

The Human Condition, first published in 1958, is Hannah Arendt’s account of how “human activities should be and have been understood throughout Western history.

Arendt is interested in the active life as contrasted with the contemplative life and concerned that the debate over the relative status of the two has made us overlook meaningful insights about the active life and how it has changed since ancient times.

She distinguishes three sorts of activity, labor, work, and action, and discusses how they have been affected by changes in Western history.

Here are some thoughts by Hannah Arendt from The Human Condition and other books, many of which are in the TU Library collection:

It is, in fact, far easier to act under conditions of tyranny than it is to think.

- The Human Condition (1958)

Political questions are far too serious to be left to the politicians.

- Men in Dark Times (1968)

In a head-on clash between violence and power, the outcome is hardly in doubt. Nowhere is the self-defeating factor in the victory of violence over power more evident than in the use of terror to maintain domination, about whose weird successes and eventual failures we know perhaps more than any generation before us. Violence can destroy power; it is utterly incapable of creating it.

- On Violence (1970)

The most radical revolutionary will become a conservative the day after the revolution.

- The New Yorker (1970)

The moment we no longer have a free press, anything can happen. What makes it possible for a totalitarian or any other dictatorship to rule is that people are not informed; how can you have an opinion if you are not informed? If everybody always lies to you, the consequence is not that you believe the lies, but rather that nobody believes anything any longer. This is because lies, by their very nature, have to be changed, and a lying government has constantly to rewrite its own history. On the receiving end you get not only one lie — a lie which you could go on for the rest of your days — but you get a great number of lies, depending on how the political wind blows. And a people that no longer can believe anything cannot make up its mind. It is deprived not only of its capacity to act but also of its capacity to think and to judge. And with such a people you can then do what you please.

- New York Review of Books (1974)

The cultural treasures of the past, believed to be dead, are being made to speak, in the course of which it turns out that they propose things altogether different than what had been thought.

- “Martin Heidegger at Eighty,” in Heidegger and Modern Philosophy: Critical Essays (1978)

Persecution of powerless or power-losing groups may not be a very pleasant spectacle, but it does not spring from human meanness alone. What makes men obey or tolerate real power and, on the other hand, hate people who have wealth without power, is the rational instinct that power has a certain function and is of some general use. Even exploitation and oppression still make society work and establish some kind of order. Only wealth without power or aloofness without a policy are felt to be parasitical, useless, revolting, because such conditions cut all the threads which tie men together. Wealth which does not exploit lacks even the relationship which exists between exploiter and exploited; aloofness without policy does not imply even the minimum concern of the oppressor for the oppressed. […]

A mixture of gullibility and cynicism had been an outstanding characteristic of mob mentality before it became an everyday phenomenon of masses. In an ever-changing, incomprehensible, world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything is possible and that nothing was true. The mixture in itself was remarkable enough, because it spelled the end of the illusion that gullibility was a weakness of unsuspecting primitive souls and cynicism the vice of superior and refined minds. Mass propaganda discovered that its audience was ready at all times to believe the worst, no matter how absurd, and did not particularly object to being deceived because it held every statement to be a lie anyhow. The totalitarian mass leaders based their propaganda on the correct psychological assumption that, under such conditions, one could make people believe the most fantastic statements one day, and trust if the next day they were given irrefutable proof of their falsehood, they would take refuge in cynicism; instead of deserting the leaders who had lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their superior tactical cleverness.

- The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951)

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)