Thammasat University students interested in ASEAN studies, history, political science, philosophy, and related subjects may find it useful to participate in a free 27 January Zoom webinar on Situating Democracy in Southeast Asia: Democratic Deficits, Challenges and Perspectives.

The event, on Saturday, 27 January 2024 at 11am Bangkok time, is presented by the Graduate School of Global Studies, Sophia University, Tokyo, Japan.

The TU Library collection includes several books about different aspects of democracy in Southeast Asia.

Students are invited to register at this link:

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLScw8fKWqsb7uRHirKCSqbkJSwlltq7zpwlh3FUEvE14behX4A/viewform

The keynote speaker will be Professor Mark R. Thompson, who teaches politics as well as Asian and International Studies at City University of Hong Kong (CUHK).

Also speaking will be Khoompetch Kongsawat, a doctoral degree candidate in the Division of International Relations, Sophia University.

A student of international security, international relations theory, international politics, diplomacy, security studies, global studies, and international development, Khun Khoompetch will speak on The Decline of Authoritarian Regime in Thailand?

Another presenter will be Tuwanont (Dee) Phattharathanasut, a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) research fellow and doctoral degree candidate at the Graduate School of Asia-Pacific Studies, Waseda University, Japan.

Khun Tuwanont’s research interests include political sociology, youth and student activism, transnationalism, and memory, with a particular focus on the transnational connectivity of youth activism in Northeast and Southeast Asia.

He will speak on The Milk Tea Alliance and its Implication on Southeast Asia and Beyond.

An August 2023 article posted on the website of the Council on Foreign Relations stated:

- The State of Democracy in Southeast Asia Is Bad and Getting Worse

By 2020, with the state of democracy already in dire shape, it seemed that things couldn’t get worse. And yet, in the past few years, they have.

Just when it seemed that the state of democracy in Southeast Asia, already in dire shape, could not get worse, it did. In the past month alone, increasingly autocratic Cambodia staged a sham election in which the main opposition party was banned and the ruling party of longtime Prime Minister Hun Sen took nearly every seat. In Thailand, where the progressive Move Forward party won a plurality of seats in May elections, military-aligned parties and royalist forces have used every tool possible to block its leader, Pita Limjaroenrat, from being named prime minister. Meanwhile, Myanmar’s junta keeps promising and postponing their own sure-to-be sham elections, while engaged in a civil war that has seen its armed forces intensify their massive rights abuses. These are but a few examples of how democracy is going from bad to worse across Southeast Asia.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the region seemed to offer a model for democratization for other developing countries. Today, Southeast Asia is a long way from that promising period, with Timor-Leste the only fully free democracy according to Freedom House’s rankings, despite its poverty and isolation.

Back then, Indonesia was embarking on a dramatic experiment with decentralization, designed to broaden democracy after the fall of longtime dictator Suharto. Thailand was classified by Freedom House as a fully free democracy. The Philippines’ democracy remained strong in the wake of its 1980s “People Power” movement that toppled the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos. And countries from Malaysia to Cambodia were making strides toward greater freedom. Within the next decade, newly independent Timor-Leste and then Myanmar would join them.

By the 2010s, democracy was already beginning to regress in Southeast Asia. […] The Philippines’ democracy floundered under mercurial and autocratic former President Rodrigo Duterte, who took office in 2016. Myanmar’s democratic transition, which began in 2011 and gathered steam by 2015, soon faltered, with massive killings of the Rohingya, continued military dominance of many ministries and a failure to create the federal state that is essential for democracy to work there. Indonesia, the region’s democratic linchpin, started to reverse course under President Joko Widodo, who was elected in 2014 claiming to be a force for democratic change but failed to implement many of his promised reforms. Singapore has remained dominated by the People’s Action Party, and Vietnam, which had made some minor moves toward greater freedoms early in the 2010s, returned to harsh autocracy.

It seemed by 2020 that things couldn’t get worse. And yet, in the past few years, they have. After winning the recent sham elections in Cambodia, Hun Sen announced he was handing power to his son Hun Manet, creating the Southeast Asian equivalent of a North Korean dynastic transition. The move, which was announced ahead of the elections but can hardly be said to enjoy popular support, makes it likely that Cambodia will see both greater corruption, as Hun Manet spreads patronage around to consolidate his rule, and continued harsh repression, since he may feel it necessary to keep a tight lid on dissent during a potentially fragile transition. […]

Myanmar’s junta, which crushed that country’s weak and troubled democracy with a February 2021 coup, now faces a serious threat to its existence from emboldened resistance forces that control large portions of the country. But even if the junta is ultimately defeated, that will leave the country in the hands of multiple heavily armed resistance organizations, all awash in weapons and with minimal bonds to each other besides their antipathy to the military regime. Indeed, some of the groups are sworn enemies. That is not a promising landscape for the emergence of democracy.

Even three of the stronger and bigger democracies in the region are backsliding. Duterte badly undermined Philippine democracy, and while his successor, President Ferdinand Marcos, has surprised observers—especially given his pedigree—by moderating some of Duterte’s worst excesses in economic and foreign policy, it remains to be seen if he will follow through to repair all the damage to the country’s human rights landscape. In Indonesia, in addition to faltering on promised reforms and allowing regressive criminal laws to be passed, Jokowi has expanded the powers and influence of the armed forces, which have a history of massive human rights abuses. With greater control of governmental functions, the Indonesian military could further dilute democracy.

And in Malaysia, while Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim fought for decades as an opposition leader for democratic reforms, he finally won the top job thanks to a coalition government that includes the United Malays National Organization, or UMNO, the longtime, autocratic party that ruled the country for decades. To keep UMNO placated, Anwar has been quiet about many human rights issues, at times even appearing to have lost control of his government to UMNO. […]

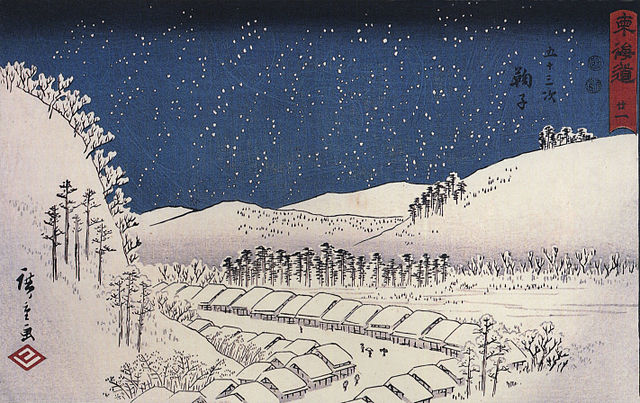

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)