Through the generosity of the late Professor Benedict Anderson and Ajarn Charnvit Kasetsiri, the Thammasat University Library has newly acquired some important books of interest for students of Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) studies, political science, sociology, and related fields.

They are part of a special bequest of over 2800 books from the personal scholarly library of Professor Benedict Anderson at Cornell University, in addition to the previous donation of books from the library of Professor Anderson at his home in Bangkok. These newly available items will be on the TU Library shelves for the benefit of our students and ajarns. They are shelved in the Charnvit Kasetsiri Room of the Pridi Banomyong Library, Tha Prachan campus.

Among them is a newly acquired book that should be useful to TU students who are interested in literature, cultural studies, English history, sociology, gender studies, and related subjects.

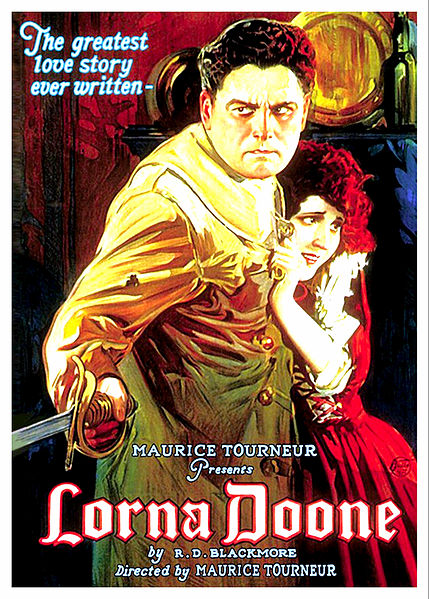

Lorna Doone: A Romance of Exmoor is a novel by the English author Richard Doddridge Blackmore, published in 1869.

It is a romance based on a group of historical characters and set in the late 1600s in Devon and Somerset, particularly around the East Lyn Valley area of Exmoor.

The TU Library collection includes several books by and about Richard Blackmore.

The term romance is often used to describe a type of novel which includes remarkable events, unlike fiction which is based on realistic descriptions of society.

Often romances are in the form of historical novels.

Examples of historical romances include the novels of Sir Walter Scott, a number of which are in the TU Library collection.

Lorna Doone was admired by such important writers as Robert Louis Stevenson, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Thomas Hardy, and George Gissing, all of whom are represented in the TU Library collection.

The book was so popular that it is considered to have inspired the name of a cookie first manufactured in 1912, Lorna Doone, a brand of golden, square-shaped shortbread produced by Nabisco.

As a historical romance, Lorna Doone describes real events and places.

One such was The Great Frost of 1683–1684 across England, reported as the worst in British history.

During the Frost, the surface of the River Thames was reported as frozen to the depth of one foot (30 cm).

Fairs are known to have been held on the frozen Thames with booths and stalls set up on the ice where vendors sold food, beer, and wine.

Students of history may look to descriptions in fiction to get a sense of such events.

Here is an excerpt from Lorna Doone about the Great Frost:

It must have snowed most wonderfully to have made that depth of covering in about eight hours. For one of Master Stickles’ men, who had been out all the night, said that no snow began to fall until nearly midnight. And here it was, blocking up the doors, stopping the ways, and the water courses, and making it very much worse to walk than in a saw-pit newly used. However, we trudged along in a line; I first, and the other men after me; trying to keep my track, but finding legs and strength not up to it. Most of all, John Fry was groaning; certain that his time was come, and sending messages to his wife, and blessings to his children. For all this time it was snowing harder than it ever had snowed before, so far as a man might guess at it; and the leaden depth of the sky came down, like a mine turned upside down on us. Not that the flakes were so very large; for I have seen much larger flakes in a shower of March, while sowing peas; but that there was no room between them, neither any relaxing, nor any change of direction.

Watch, like a good and faithful dog, followed us very cheerfully, leaping out of the depth, which took him over his back and ears already, even in the level places; while in the drifts he might have sunk to any distance out of sight, and never found his way up again. However, we helped him now and then, especially through the gaps and gateways; and so after a deal of floundering, some laughter, and a little swearing, we came all safe to the lower meadow, where most of our flock was hurdled.

But behold, there was no flock at all! None, I mean, to be seen anywhere; only at one corner of the field, by the eastern end, where the snow drove in, a great white billow, as high as a barn, and as broad as a house. This great drift was rolling and curling beneath the violent blast, tufting and combing with rustling swirls, and carved (as in patterns of cornice) where the grooving chisel of the wind swept round. Ever and again the tempest snatched little whiffs from the channelled edges, twirled them round and made them dance over the chime of the monster pile, then let them lie like herring-bones, or the seams of sand where the tide has been. And all the while from the smothering sky, more and more fiercely at every blast, came the pelting, pitiless arrows, winged with murky white, and pointed with the barbs of frost. […]

All our house was quite snowed up, except where we had purged a way, by dint of constant shovellings. The kitchen was as dark and darker than the cider-cellar, and long lines of furrowed scollops ran even up to the chimney-stacks. Several windows fell right inwards, through the weight of the snow against them; and the few that stood, bulged in, and bent like an old bruised lanthorn. We were obliged to cook by candle-light; we were forced to read by candle-light; as for baking, we could not do it, because the oven was too chill; and a load of faggots only brought a little wet down the sides of it.

For when the sun burst forth at last upon that world of white, what he brought was neither warmth, nor cheer, nor hope of softening; only a clearer shaft of cold, from the violet depths of sky. Long-drawn alleys of white haze seemed to lead towards him, yet such as he could not come down, with any warmth remaining. Broad white curtains of the frost-fog looped around the lower sky, on the verge of hill and valley, and above the laden trees. Only round the sun himself, and the spot of heaven he claimed, clustered a bright purple-blue, clear, and calm, and deep.

That night such a frost ensued as we had never dreamed of, neither read in ancient books, or histories of Frobisher. The kettle by the fire froze, and the crock upon the hearth-cheeks; many men were killed, and cattle rigid in their head-ropes. Then I heard that fearful sound, which never I had heard before, neither since have heard (except during that same winter), the sharp yet solemn sound of trees burst open by the frost-blow. Our great walnut lost three branches, and has been dying ever since; though growing meanwhile, as the soul does. And the ancient oak at the cross was rent, and many score of ash trees. But why should I tell all this? the people who have not seen it (as I have) will only make faces, and disbelieve; till such another frost comes; which perhaps may never be.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)