Thammasat University students interested in history, cultural studies, ethnology, anthropology, China, the allied health sciences, and related subjects may find it useful to participate in a free 15 April webinar on Form Follows Fever: Malaria and the Construction of Hong Kong, 1841–1849.

The event, on Monday, 15 April 2024 at 4pm Bangkok time, is organized by the School of Humanities, Centre for the Study of Globalization and Cultures and Centre for the Study of Globalization and Cultures, The University of Hong Kong (HKU).

The TU Library collection includes some books about different aspects of healthcare in Hong Kong.

The speaker will be Dr. Christopher Cowell who teaches architectural history and theory at London South Bank University, the United Kingdom.

He is the author of Form Follows Fever: Malaria and the Construction of Hong Kong, 1841–1849.

The event website describes the book as the

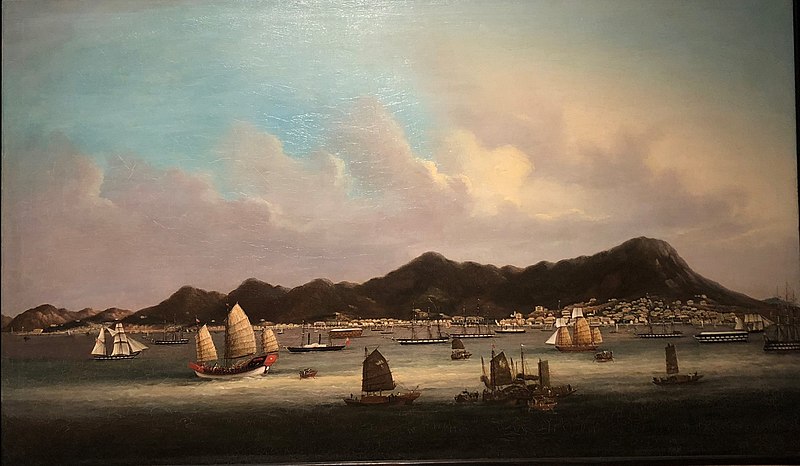

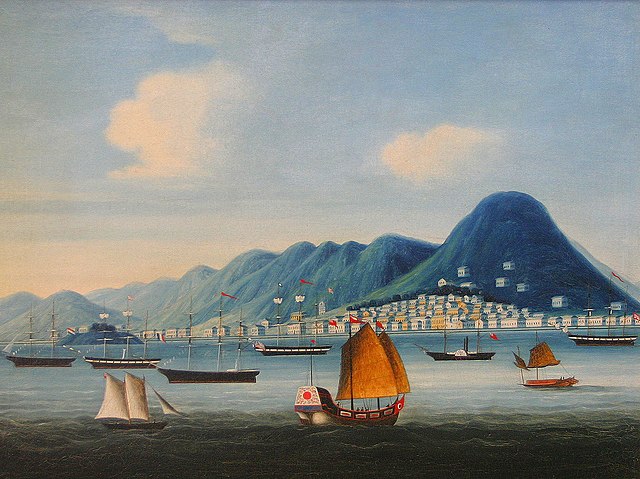

first in-depth account of the turbulent years of initial urban settlement and growth of colonial Hong Kong across the 1840s. During this period, the island gained a terrible reputation as a diseased and deadly location. Malaria, then perceived as a mysterious vapor or miasma, intermittently carried off settlers by the hundreds. Various attempts to arrest its effects acted as a catalyst, reconfiguring both the city’s physical and political landscape, though not necessarily for the better. However, Hong Kong’s ‘construction’ was not just physical but also imagined. By drawing upon many unpublished textual sources, “Form Follows Fever” sheds new light on a period often considered the colonial Dark Ages in the territory’s history.

The forthcoming book will be available to TU students through the TU Library Interlibrary Loan (ILL) system.

Students are invited to register for the event at this link:

https://hkuems1.hku.hk/hkuems/ec_regform.aspx?guest=Y&UEID=93295

With any questions or for further information, please write to

gchallen@hku.hk

In a 2018 article in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch, Dr. Ria Sinha observed:

Abstract

Despite Hong Kong’s association with infectious disease, it is easy to overlook the long presence and significant impact of malaria on its history. The experience is complex, personal and of particular interest because it spanned key developments in both understanding and controlling the disease.

High mortality shaped Hong Kong’s emergence, dictating the urban layout of the new colony and driving local production of scientific and medical expertise. Yet malaria eradication followed a discontinuous course, dependent on step-wise progress in scientific knowledge, medical expertise, colonial government policy, targeted intervention, public education and surveillance.

As an emerging disease ‘hotspot’, these factors remain relevant in twentyfirst century Hong Kong as inherent features of local infectious disease preparedness planning. This paper explores the complex socio-ecological relationship between malaria, people and the environment and examines malaria’s fluid identity in the Hong Kong context. Focusing on three key phases in Hong Kong’s experience of malaria it examines how this evolving identity influenced attempts to control the disease and contends that the need to make Hong Kong a successful colony was both a driver of malaria and the means by which eradication was eventually achieved.

The article begins:

Hong Kong has an enduring association with infectious disease. Its short history is punctuated by epidemics of such diseases as plague, SARS and avian influenza. Other disease threats are represented today by the comparatively rare, local mosquito-borne dengue fever and Japanese encephalitis. In this context it is perhaps easy to forget the long presence and significant impact of another mosquito-borne disease, malaria, on Hong Kong’s development. From pre-colonial times through more than a century of British

rule, malarial fevers were a common scourge, inflicting considerable morbidity and mortality among both Chinese and foreign populations.

The Hong Kong experience of malaria is complex, personal and of special interest because it spans key scientific developments in both understanding and controlling the disease. Malaria was not just a medical problem, but potentially a military, political, social and economic impediment to the success of the colony. The mortal impact of the disease during the formative years of the colony was instrumental in shaping Hong Kong’s emergence. It dictated the urban layout of the new colony and drove local production of scientific and medical expertise. The eradication of malaria in Hong Kong, however, followed a discontinuous course, dependent on step-wise progress in scientific knowledge, medical expertise, colonial government policy, targeted intervention, public education and surveillance. These factors remain relevant in twenty-first century Hong Kong, an emerging disease ‘hotspot’, as inherent features of local infectious disease preparedness planning.

This paper explores the complex socio-ecological relationship between malaria, people and the environment, and examines malaria’s fluid identity in the Hong Kong context. Focusing on three key phases in Hong Kong’s experience of malaria it examines how this evolving identity influenced attempts to control the disease and contends that the need to make Hong Kong a successful colony was both a driver of malaria and the means by which eradication was eventually achieved.

The article’s conclusion, in part:

Memories of malaria are imprinted on Hong Kong; in the landscape, urban planning, the people and the medical system. Malaria inflicted significant hardship on the fledgling colony and resisted multiple attempts to monopolise the landscape, forcing incoming settlers to acclimatise both physically and mentally to the environment. Determination and resilience were necessary to build and develop the colony from the ground up in the face of considerable intimidation from infectious disease. Perhaps the largest disease burden, however, was borne by the migrant labourers, drawn to the colony by employment opportunities. Certainly, the British cause, not to give up on Hong Kong, sacrificed thousands of lives. […]

The persistence of malaria in Hong Kong was further complicated by the high degree of regional population mobility and cultural segregation. Societal crises, including political tensions and conflict in neighbouring countries were notable and persistent drivers of mass movements of Chinese migrants and refugees into Hong Kong, overwhelming medical services, topping up the local parasite population and diverting attention and resources from sustained mosquito control activities. Hong Kong’s position as an international port city and trading hub attracted transient medical expertise, but also maintained

extraterritorial infection routes. In this sense, and despite its antagonistic connection, colonisation was both a driver and a means of defeating malaria in Hong Kong. Notwithstanding the accumulation of knowledge and expertise regarding the malaria situation in Hong Kong from the 1930s, it was not until the post-war period and its accompanying changes in social structure and rapid urbanisation, that eradication became a possibility, as Morrison had alluded to more than a century earlier.

Ongoing importation of malaria cases is an important reminder of Hong Kong’s global interconnectedness, as an international business hub and popular holiday destination. The territory remains a thoroughfare, hosting a daily transient population of healthy and unhealthy people alike and its regional connectedness potentially increases the risk of reintroducing malaria.

The question is whether Hong Kong’s pestilential past is truly behind it, or whether its commercial success could prove to be an Achilles heel in terms of vulnerability to future disease threats?

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)