Thammasat University students interested in history, political science, international relations, sociology, humanities, comparative religion, war studies, and related subjects may find it useful to participate in a free 5 June webinar on Escaping the Holocaust: The Mir Yeshiva from Vilna to Shanghai and beyond.

The event, on Wednesday, 5 June 2024 at 11:30am Bangkok time, is organized by the Hong Kong Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences, The University of Hong Kong (HKU).

The TU Library collection includes some books about the Holocaust and China.

The speaker will be Emeritus Professor Jay Winter who teaches history at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, the United States of America.

The TU Library collection includes published historical research by Professor Winter.

The event website explains:

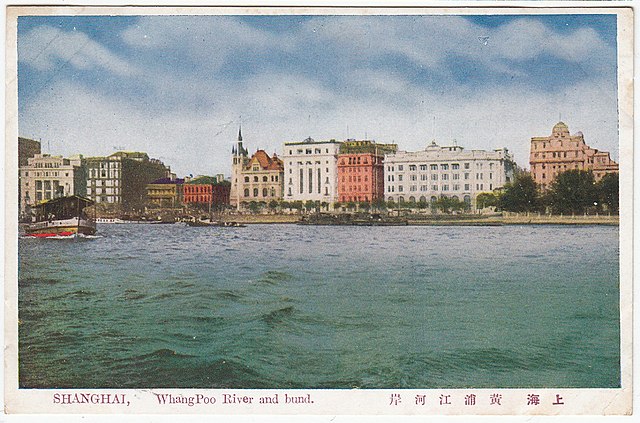

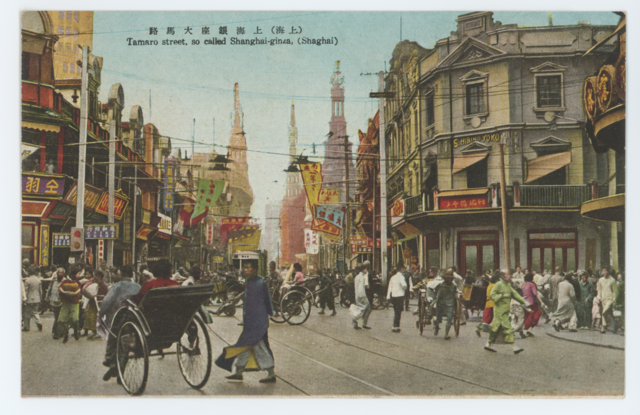

During the Second World War the Nazis wiped out the world of Jewish scholarship centred in Talmudic academies or ‘Yeshivot’ in Europe. Remarkably, one academy survived intact. The Mir yeshiva was based in Byelorussia, but in 1939 fled Stalin to independent Lithuania. The outbreak of war put an end to Lithuanian independence, and placed the large Jewish world of Eastern Europe in an impossible situation, between Stalin and Hitler. This paper tells the story of how one Yeshiva escaped to China, keeping alive a way of life almost entirely extinguished elsewhere.

Students are invited to register for the event at this link:

https://hku.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_hNs2z1qhTwaRc0xUoY0K2A

With any questions or for further information, please write to

smblai@hku.hk

Professor Winter gave an interview posted on the Yale News website. Excerpts:

Jay Winter, the Charles J. Stille Professor of History and editor of the recently published three-volume “Cambridge History of the First World War,” recently spoke to YaleNews about how WWI has impacted the 20th century, what lessons can be learned from the conflict, and the emergence of a global history of the so-called “Great War.” The following is an edited version of that conversation. […]

My mother’s family was wiped out in the Holocaust, and its shadow haunted my childhood. Writing about mourning practices in the aftermath of the First World War was an indirect way of confronting indirectly part of my childhood. […]

The Great War, as the British term it, turned war from a killing machine into a vanishing act. Half of those who died in the war have no known graves — that is five million people. Hence, the cult of names emerged in the war, since all that is left of these people are their names. And that cult of naming after the 1914–1918 conflict has extended to the 6 million victims of the Holocaust, the names on Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial wall, the names of the “disappeared” in Latin America, and the names of those killed on 9/11. Here is but one way in which the Great War has shaped the last century and this one as well. […]

Since the 1980s, a group of historians have emerged who are “trans-national historians.” These are people who are born in one country, trained in another, and frequently at work in a third. Thus a national perspective on the war has given way to a comparative perspective, in which the state is not the focus of research. This has been productive, since the war was bigger than all of the states that waged it. It was truly global, and a global history of the war has emerged to reflect its revolutionary character. […]

The anniversary of the outbreak of the war has buried the word “celebration.” We don’t celebrate the war; to do so has a taste as of ashes. We see it as a global catastrophe, which opened the door to the Second World War and the Holocaust. Hence, commemorating the Great War necessarily has a pacifist character. No cause justified the slaughter of 10 million men and the mutilation of another 20 million. […]

In another interview posted on the website of History News Network, Professor Winter stated:

There are two contexts in which my interest in the subject developed. The first is that I come from a family, a part of which was destroyed in the Holocaust. There’s always been a shadow in my life from early on. I was born in 1945.

The Holocaust has an area that’s too dark to go into, a black hole. In a way, I didn’t know it at the time I when I went into the First World War that I was approaching the antechambers of the memories I had as a child and the consequences of large numbers of people being wiped out. The First World War is at one remove from the dark memories of my childhood. It is close enough to draw me too it, but not too close to the horrors of the Holocaust.

The other reason is that, when I was an undergraduate at Columbia, I went to a wonderful seminar run by a great German historian, Fritz Stern, in 1965, and I can say that I’m still in that seminar. I was able to take Fritz, his wife and son to dinner in 2015, 50 years to the day after I had that experience of being in the seminar. I told him then that whatever has happened in the 50 intervening years, he’s the one to blame. It’s all his fault that I became an historian of what in Europe is called the Great War.

What’s more important is that, when I was finishing my BA in the mid-1960s, the context of the Vietnam War influenced me significantly. This context accounts for my interest in the Great War. The Vietnam war, to a degree, was America’s First World War. One war of brutality and futility drew me to another one in my historical work. The American experience of the bitterness, the ugliness of war really hit home in the late 1960s, and countered the myths surrounding the Second World War as the good war. There was a lot of suffering to be sure in 1939-45, and I certainly don’t underestimate that, but it’s in a separate category, one in which war had a ‘meaning’, a justification. Nothing justified the carnage of the First World War, and nothing justified the carnage of Vietnam. This equivalence mattered to me in my early years.

When I was finishing my undergraduate years and decided I didn’t want to stay in the States because of Vietnam and went to Cambridge to do my doctorate, it was partly because I saw a parallel to what was happening in Vietnam and the First World War: a stupid, meaningless war in which suffering was unlimited. We willingly employed staggering levels of violence in attempting to subdue the national liberation struggle in Vietnam, and our leaders lacked the imagination or ability to control it. That sense of the betrayal of the men who fought by the men who led them into the quagmire stood with me for a long time.

I should add that I was entered an undefined field when I decided to write about the First World War. The history of the First World War wasn’t really a subject when I started 50 years ago. It was only beginning to come into focus. The archives were only opening around 1964, 50 years after the start of the war.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)