Thammasat University students who are interested in film, performance art, Asian studies, gender studies and related subjects may find a new Open Access book available for free download useful.

To Be an Actress: Labor and Performance in Anna May Wong’s Cross-Media World is by Professor Yiman Wang, who teaches film and digital media at the University of California, Santa Cruz, the United States of America.

Her book may be downloaded free at this link:

https://luminosoa.org/site/books/m/10.1525/luminos.189/

The publisher’s description explains:

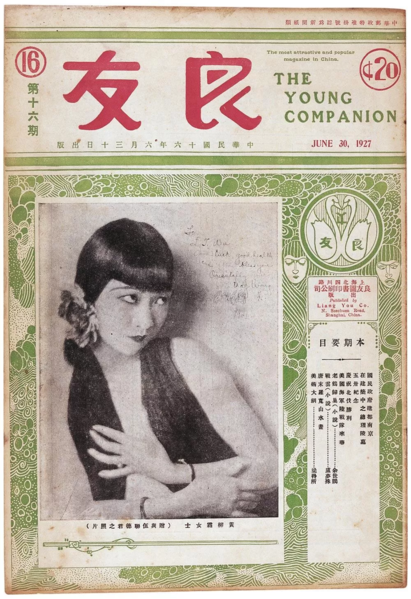

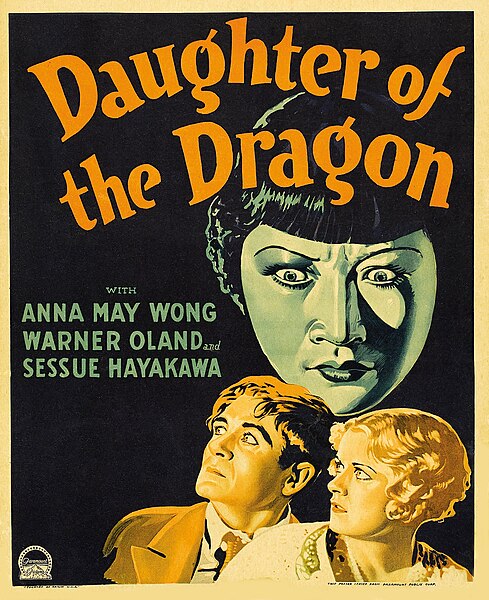

Between 1919 and 1961, pioneering Chinese American actress Anna May Wong established an enduring legacy that encompassed cinema, theater, radio, and American television. Born in Los Angeles and growing up amid the suspicion and scrutiny epitomized by the Chinese Exclusion Act, Wong—a defiant misfit—innovated nuanced performances to subvert the racism and sexism that beset her life and career. This critical study of her cross-media and transnational career marshals extraordinary archival research and takes a multifocal approach to illuminate a lifelong labor of performance. Viewing Wong as a performer and worker, not just a star, Yiman Wang adopts a feminist decolonial perspective to speculatively meet her subject as an interlocutor. In doing so, she invites a reconsideration of racialized, gendered, and migratory labor as the bedrock of the entertainment industries.

The TU Library collection includes a number of other books that discuss the life and career of Anna May Wong.

The website of the United States Mint offers information about the coin issued in 2022 to honor Anna May Wong:

The Anna May Wong Quarter is the fifth coin in the American Women Quarters Program. Anna May Wong was the first Chinese American film star in Hollywood.

Wong was born January 3, 1905, in Los Angeles. Her birth name was Wong Liu Tsong, and her family gave her the English name Anna May. She was cast in her first role as an extra in the film “The Red Lantern” (1919) at 14 and continued to land small roles as extras until her first leading role in “The Toll of the Sea” (1922).

Her career spanned motion pictures, television, and theater. She appeared in more than 60 movies, including silent films and one of the first movies made in Technicolor. Wong also became the first Asian American lead actor in a U.S. television show for her role in “The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong” (1951).

After facing constant discrimination in Hollywood, Wong traveled to Europe and worked in English, German, and French films. She also appeared in productions on the London and New York stages.

Wong was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960. She died on February 3, 1961. She is remembered as an international film star, fashion icon, television trailblazer, and a champion for greater representation of Asian Americans in film. She continues to inspire actors and filmmakers today. […]

The reverse (tails) features a close-up image of Anna May Wong with her head resting on her hand, surrounded by the bright lights of a marquee sign.

The new book’s Introduction begins:

The completion of this book coincided with a juncture of profound irony. On the one hand, Anna May Wong (1905–61), the pioneering Asian American female performer, received unprecedented recognition not only for her indelible contribution to American cinema, but also as an exemplary woman of color whose face was newly memorialized on a quarter coin issued in 2022, and whose figure found a new embodiment in the red dragon–gowned Barbie doll in Mattel’s Barbie Inspiring Women series, released for the Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage

On the other hand, the COVID-19 pandemic that brought the world to a prolonged halt in 2020 also unleashed anti-Asian hate in Euro-America, resulting in skyrocketing crimes against East Asian–presenting persons and communities who became the easy target of a racist surge. How do we square the enthusiastic media celebration of Wong and other prominent Asian-heritage North Americans with the rampant violence against those who look like them?

To put it more bluntly, how did anti-Asian hate become so infectious and egregious even as the mainstream media and popular culture were vigorously promoting Asian North American legacies? Most importantly, what can Anna May Wong teach us regarding her and our never-ending battles against die-hard racism, sexism, and patriarchal nationalism that underpin the exclusionary, hierarchizing system as a whole?

Wong is a prime example for probing these pressing issues, for she embodied the conundrum of being excluded and idolized all at once; and her life-career emerged from tirelessly and resourcefully navigating this conundrum.

Nearly one hundred years ago, just nine years after her screen debut in 1919, Wong already felt the frustration of a stalling career in Hollywood due to the latter’s discriminatory nature compounded with the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882–1943). In 1928, she made her first cross-Atlantic trip, landing in Berlin for a one-picture contract, which led to a series of film and theater engagements in Germany, France, the UK, and Austria.

Her first European trip from 1928 to 1930 turned out to be a career-defining period that established her international celebrity in interwar Europe and spurred further trips to Europe in the mid-1930s, to China in 1936, and to Australia in 1939,

Throughout her peripatetic life-career, Wong crossed nations, oceans, media forms, and technologies in a resilient search for more fulfilling work in a more equitable work environment. She appeared in over seventy films and television shows, in addition to extensive theater work (encompassing Broadway, the British legitimate theater, and vaudeville shows in Euro-America and Australia) and some radio shows. Her work off camera and off stage were just as important, representing her painstaking retraining and hustle in response to changing media terrains and audience expectations, as well as to the dramatically shifting Sino- American relationship from interwar cosmopolitanism through World War II to Cold War.

A globe-trotter and a transnational migrant worker during the era of Chinese Exclusion, Wong charted out a cross-media world, fostering and greeting her multinational audiences then, now, and into the future. Her life-career bears witness to the mainstream society’s simultaneous discrimination and idolization, both due to her misfit “Oriental” femininity. Furthermore, her cross-media world shows us methods of critiquing and navigating the conundrum of being included as the good object and being excluded as the bad object all at once. My entry point to Wong’s brave cross-media world is the glaring gap between her words of barbed humor and the stultifying mainstream media coverage of her.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)