Conjoined twins, popularly referred to as Siamese twins, are a rare phenomenon, estimated to occur in anywhere between one in 49,000 births to one in 189,000 births, with a somewhat higher incidence in southwest Asia and Africa.

Recognizing that the case of conjoined twins is a rare condition where the estimated incidence can be 1 in 50,000 births, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly decided to proclaim 24 November as World Conjoined Twins Day.

The Assembly emphasized the need to address the condition of conjoined twins, by raising awareness of their cases at all levels and through a life-course approach, in cooperation with relevant United Nations agencies and other stakeholders, as well as by advocating for their well-being and social inclusion, while taking into account relevant agreed international standards, norms and principles.

A book in the Thammasat University Library collection, Inseparable: The Original Siamese Twins and Their Rendezvous with American History, is by Professor Yunte Huang, who teaches English at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Lingnan University, Hong Kong.

This volume joins others in the TU Library about the same subject.

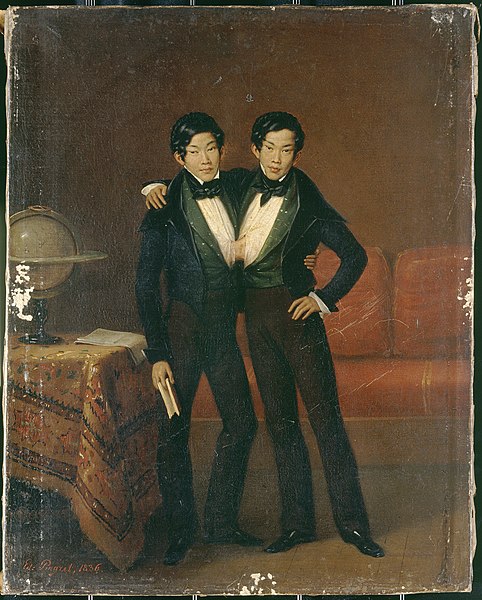

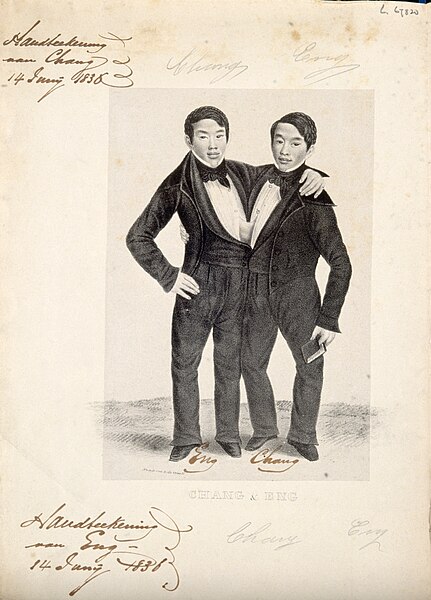

His book gives historical context to the celebrated life story of In and Chun (1811-1874), conjoined twins born in 1811 in the Mae Klong Valley, Samut Songkhram Province, Siam, during the reign of King Rama II.

Their father, Ti-aye, a fisherman, was of Chinese origin and their mother, Nok, possibly of Chinese-Malay background, so the boys were known as the Chinese twins in their homeland. Joined at the sternum by a piece of cartilage, the boys were athletic and enjoyed playing badminton and performing tumbling tricks despite their disability.

This caught the eye of a traveling British merchant who exported them to America to exhibit them in sideshows.

Renamed Chang and Eng, they would later convert to Christianity and adopt the family name Bunker, as they settled down in North Carolina. They both married and had several children, some of whom fought for the Confederacy in the American Civil War.

They became so famous as performers that a new term, Siamese twins, was used until fairly recently to describe conjoined twins.

The book examines the paradox of how Chang and Eng Bunker, although themselves targets of race prejudice, owned African-American slaves in the pre-Civil War era.

He also notes how they boldly fought for their own independence from abusive employers a few years after they arrived in America.

In an online interview, Professor Huang was asked:

If you could have met Chang and Eng, what one thing would you have asked them?

His reply, in part:

My own question for them would be, “Why did you never go back to Siam?” As an immigrant, I can feel in my bones the pang of nostalgia, memories of my old country running as deep as genetic coding. After leaving their family in Siam at the young age of 17, the twins never went back. I’m curious to know why.

Here is an excerpt from Professor Huang’s book:

According to some biographers, the twins, prior to their wedding, had consulted with physicians in Philadelphia and were ready to go under the knife. Aghast at the news, Sarah and Adelaide begged the men not to follow through with the dangerous procedure and reassured the men that they would be happy to marry them “as they were.”

The skeptics must have been even more surprised when they heard, ten months after the wedding, that each couple had produced a “fine, fat, bouncing daughter.” On February 10, 1844, Sarah and Eng became proud parents of a baby girl named Katherine; only six days later, Adelaide and Chang welcomed into the world a baby girl named Josephine.

If there was any lingering doubt about the procreative aspect of the unions, there would be even more evidence to put the matter to rest: In their lifetime, the two couples would produce twenty-one children in total, with Eng and Sarah claiming eleven and Chang and Adelaide, ten. Out of these twelve daughters and nine sons, two would die at young ages from accidents, while two were deaf and mute. There were no twins, let alone conjoined twins or babies with any other discernible deformity…

A year after the birth of their first children, the twins and their wives celebrated the arrival of two more additions to the brood, born again only about a week apart: a baby girl named Julia for Eng and Sarah on March 31, 1845, and the first boy, named Christopher, for Chang and Adelaide on April 8.

As the family grew, the house in Traphill became too small for them. In the spring of that year, Chang and Eng purchased a farm in nearby Surry County for $3,750. Straddling bubbling Stewart’s Creek outside the village of Mount Airy, this 650-acre farmland would become their Xanadu—or, more pertinent and closer to home, their Monticello.

On this new land, Chang and Eng—two brothers formerly sold into indentured servitude and treated no better than slaves—began farming by using black slaves. […]

Soon after their relocation to Surry County, the twins began to purchase more slaves and even engage in slave trading. What is unquestionably clear is that the twins by this time had adopted the mindset, in all its permutations, of the oppressor class, the whites who owned slaves. […]

According to the twins’ descendant Melvin Miles, Chang and Eng would buy slaves younger than eight, keep them, and work them until they were in their early twenties, when they would be sold or traded for younger ones to carry on the work. With very few exceptions, they would not keep a male slave older than twenty-five, because “the twins thought that by then the male slaves were of the mindset of trying to escape or rebel against their owners.” […]

How the twins treated their slaves was a contentious topic both during their lifetimes and after their deaths. There were accounts that portrayed them as humane and kind, while others described them as “severe taskmasters.” According to Judge Graves, whenever the twins took long trips, they would always bring gifts for each member of the family, “not even forgetting the colored servants down to the youngest.” […]

These descriptions of the so-called harmonious relationship between masters and slaves, suggesting that the twins “did not drive their slaves but supervised them,” were complicated by allegations to the contrary.

The first of these negative reports appeared in a newspaper article published in the Greensborough Patriot in 1852. The author of the article, who signed himself merely “D.,” did a profile of the twins, describing them as shrewd and industrious businessmen with belligerent and fiery dispositions. […]

Such an unflattering depiction of them as cruel masters drew an immediate response from the twins, who were acutely aware of the importance of public image. They shot off a long letter to the newspaper, defending their own character and integrity and objecting vehemently to the article’s claims. […]

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)