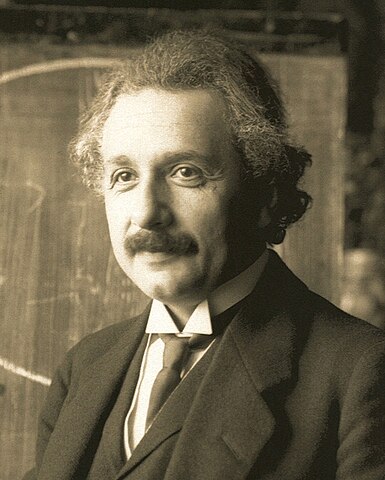

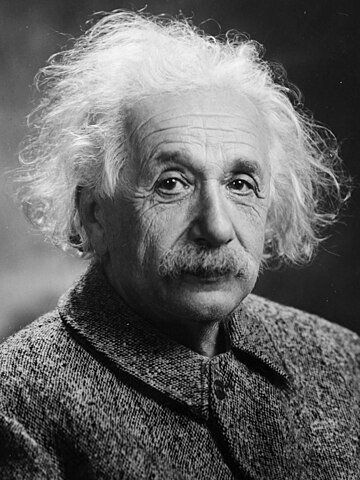

Although the scientist Albert Einstein (1879–1955) is a celebrity in Thailand as in the rest of Asia and the world, not everyone knows exactly why he is so famous. A book newly acquired by the Thammasat University Libraries should help: The complete idiot’s guide to understanding Einstein.

Its author, Gary Moring, teaches physics to non-scientists at the University of Phoenix, Arizona so he is accustomed to explaining complex scientific ideas in general terms that can be understood by most readers, including those who are not specialists. Einstein is certainly still known and respected in Thailand. Anyone who goes to Phitsanulok can admire a public statue of Einstein there, and in Bangkok an Einstein Café has opened on the second floor of The Nine Neighborhood Center, a shopping mall on Rama 9 road. The Einstein Café serves German, Italian, Thai and vegetarian dishes with a selection of European beers that are especially popular with students. On one wall of the restaurant is Einstein’s relativity formula E=mc2, which gives the impression that by sitting around eating and drinking beer, Thai people can become as smart as Einstein was. The Digital Einstein papers, which makes available online private and professional writings by Einstein, gives a different impression. Diana Kormos-Buchwald, a professor of history at the California Institute of Technology and director and general editor of the Einstein Papers states: “What I’m impressed with most is how hard working [Einstein] is. Inspiration is a very small component. He works very hard all day and every day.”

Patience and Labor.

Part of Einstein’s secret was that he worked very hard. In a long scientific career, he published over 300 papers along as well as more than 150 works on subjects other than science. He would not have approved of the self-help gurus who sometimes give public presentations in the Kingdom, telling people how to “Boost your Brain Like Einstein” or “Bring the Mind of Einstein to Your Organization.” These activities have nothing to do with the real Einstein, who worked with a large group of top-level thinkers of his day to arrive at his discoveries, taking years to arrive at some results. On some subjects, he never arrived at a satisfying result at all. Working hard for many years to make discoveries instead of expecting a quick fix from a self-help course requires lots of patience, but that is what Einstein did. Sometimes he made mistakes as every scientist does, and sometimes these errors led to important new discoveries in later years by other scientists.

Einstein in Asia

In 1922, when Einstein was still in his forties, he made a long trip to Asia, visiting Singapore, Ceylon and Japan where he lectured to large audiences. Born in Germany and living and working in Switzerland and America, Einstein was profoundly Western in outlook. Yet he admired and enjoyed his experience in the East. After his first public lecture in Japan, he was presented to Emperor Taishō at the Imperial Palace. In a letter to his son, Einstein stated that he felt that the Japanese people were “modest, intelligent, and considerate, with a true feeling for art.” He had been invited to Japan by Yamamoto Sanehiko, the director of Kaizosha, a Tokyo publishing house. Einstein and his wife traveled on the Japanese steamer Kitano Maru from Marseilles, with stopovers at Port Said, Colombo, Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai, and the port of Kobe, Japan.

Wherever he traveled, Einstein’s charm and friendly personality made a strong impression. Most audiences had little concern about whether the mass of an object is a measure of how much energy it contains, the subject of E=mc2 which has been called the “world’s most famous equation.” Nor did they care that Einstein’s work on relativity argues that the path of light as it reaches the Earth from a star bends from the gravitational force of the Sun. Even though such ideas revolutionized physics as it had been understood for centuries and changed the way people look at the world, this was not of primary importance to most of Einstein’s admirers. One Japanese writer of children’s books, Ogawa Mimei (1882-1961) attended a public presentation and approvingly called Einstein a “tender poet to be remembered nostalgically.” Miyake Yasuko, a Japanese journalist, wrote: “I once thought that all scientists were narrow-minded…with the shifty gaze of robbers, but Professor Einstein’s grand and sublime eyes changed my opinion utterly.”

Beyond these initial impressions based on looks and personality, the Japanese people did make an effort to understand what all the fuss was about in terms of Einstein’s thinking. If The complete idiot’s guide to understanding Einstein had existed at that time, doubtless many people would have read it. The reference to idiot in the title of this popular series, just like another series of bestselling books supposedly aimed at dummies, is meant by publishers to be eye-catching. Naturally it is offensive to be called either an idiot or a dummy. Some readers have pointed out that it is better to be called a dummy than an idiot, because a dummy, or ignorant person, can become smarter by learning whereas an idiot remains an idiot forever. Despite such arguments, the idiot’s guide series does have useful content and is a potentially rewarding way to approach the subjects it deals with. The TU Libraries own many other guides and descriptions of the life and work of Einstein, although some may be too technical for non-physicists.

What the Japanese did to understand Einstein.

In 1922, the Japanese people watched a German documentary film about Einstein’s theory of relativity, and there were plays and many books of popular science on the subject as well. When he wrote on a blackboard during a lecture at the University of Fukuoka, his writings in chalk were preserved forever by his respectful hosts (the same tribute was made at Oxford University, England and in Princeton, New Jersey, where Einstein spent the last years of his life).

Even those who did not fully follow the high-level scientific arguments of Einstein enjoyed trying to understand them. One Japanese humanities professor stated that at several lectures by Einstein which he attended in Tokyo, “I heard the quiet, calm sounds of his mind. His thinking advances steadily, hushed like melting spring snow, without racing ahead, sprinkling the field of knowledge with jewels of math equations.”

(all images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons).