People often yawn, hiccup, cough, and sneeze, but scientists often do not know exactly why. A book newly acquired by the Thammasat University Libraries tries to explain these mysteries.

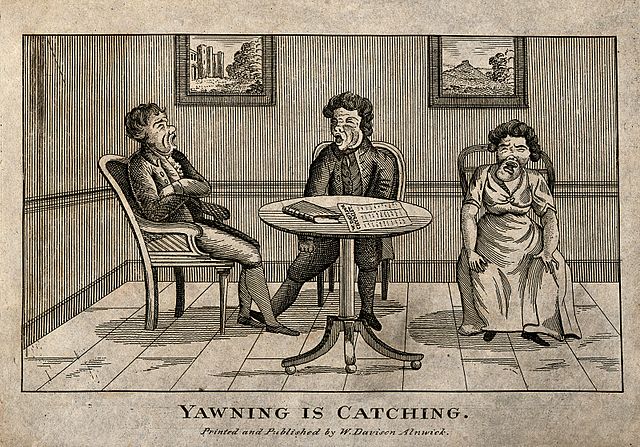

Curious Behavior : Yawning, Laughing, Hiccupping, and Beyond is written by Robert Provine, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at the University of Maryland. You may have noticed how if you see someone yawn, even in a film or on TV, you feel the urge the yawn. Some people claim to feel a need to yawn even when they read about yawning. Yet science has not been able to explain this phenomenon as yet. According to Provine, it may have something to do with human beings as social animals and the importance of empathizing with the next person. If the next person yawns, we feel we should do likewise. Provine argues that everyone can observe human behavior and think about it. The next time you are at the mall, or attending a wedding or sports event, you too can notice how people behave. So it is not necessary to be a scientist to try to puzzle out what motivates people’s actions. When people sitting in audiences cough, or cry at movies, or when they get the hiccups, these are physical reactions governed by unconscious motives.

The yawn.

When we yawn, we breathe in air at the same time as we stretch our eardrums. Then we exhale. There is even a medical term for when we yawn and stretch our arms and bodies at the same time: pandiculation. Why we do it remains unknown, Provine explains. Adults yawn the most before and after they sleep, when they are bored, and if they see someone else yawning. People think of yawning as something to do if you are tired, stressed out, sleepy, or hungry, but recent scientific studies show that it can also serve to cool off your brain. So-called contagious yawning, when you yawn because you have someone else yawn, is not limited to humans. Chimpanzees and dogs do the same thing as well as other vertebrates (animals with backbones). If a chimpanzee sees a dog yawn, it will yawn in reply; it does not require a yawn from another chimpanzee to inspire it. Provine notes that although your eyes may close at some time during a yawn, it is impossible to complete a yawn with your eyes shut. Again, no one knows why. Provine concludes: “Yawning is a response to and facilitator of change in behavioral and physiological state.”

Hiccups and coughs.

Among other behavior that Provine examines is hiccupping, which is even done by fetuses before birth. Indeed, fetuses hiccup far more than newborn children do. They also yawn more than babies after birth do. This suggests that hiccupping and yawning play some role in developing the fetus before it can breathe independently. All of the unusual activities studied by Provine seem to have some communicative or social purpose. Why do students who must sit through a boring lecture cough louder and louder as the class goes on? Do they hope that if they cough loud enough, they will drown out the speaker?

Laughing and crying.

When someone has what is called an infectious laugh, if that person sits with others and laughs, other people will feel like laughing too. Sometimes at a show the audience laughs because one of the audience members has a funny-sounding laugh, rather than laughing at what is happening onstage. Why should people laugh when they hear someone else laugh? Provine claims that people cannot laugh on command. If someone orders you to laugh right now, it will be difficult or impossible to do so. Yet the research of other scientists suggests that some people can produce authentic-sounding laughs on command. People who hear this forced laughter believe it is genuine almost half of the time, according to one 2012 experiment about the “animal nature of spontaneous human laughter.” While it may seem odd to spend time and effort to study such things as hiccups and laughter, they are part of what makes us human. Provine also observes that when people laugh during conversations, he can often find nothing obviously funny that causes their laughter. For example, if two friends say goodbye and one of them says “See you later,” they might laugh. Yet evolutionary psychologists suggest that if we cannot tell why people are laughing, it may be because we do not know enough about the people or their situation. They may not be laughing about nothing at all, but rather whatever caused their laughter has not been observed by outsiders as yet.

If you read this book, you might test out the author’s theories yourself by seeing if you happen to yawn while you are looking at the chapter about yawning. Most people think of laughing as good for us and even good for our health. Yet we do not consider that it may be a way to try to change the behavior of other people towards us. Or as Provine argues, the “idea that laughter is good for us has become so pervasive that we neglect the fact that laughter, like speech and vocal crying, is a vocalization that evolved to shape the behavior of other people. Laughter no more evolved to make us feel good or improve our health than walking evolved to promote cardiovascular fitness.”

What grabs the attention more than a baby’s cry? It cannot be ignored, which is a good thing for babies. It is their main way of communicating with the outside world. Crying happens all the time before babies can speak, but after they can say something, usually they cry less. Provine asks readers to try to remember the last time they cried and whether they were in pain or frightened at that time. Because tears are visible, they are useful for communicating to others that we feel distressed.

(all images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons).