The Thammasat University Libraries own a unique and fascinating film produced by Pridi Banomyong.

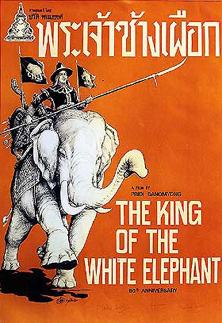

King of the White Elephant (พระเจ้าช้างเผือก or Prajao Changpeuk) was made in 1940, directed by Sunh Vasudhara. It is an historical drama based on a short novel written by Pridi which is also in the TU Libraries collection and well worth reading. The film is especially interesting in that its amateur actors were ajarns and students of Thammasat University. Another unexpected aspect is that the film was made in English. All of the Thammasat ajarns and students participating in 1940 had good enough English to act in a film in that language. The film was made for a specific purpose. Its theme was pacifism, or being against war, except in cases where invasion makes war unavoidable.

which is also in the TU Libraries collection and well worth reading. The film is especially interesting in that its amateur actors were ajarns and students of Thammasat University. Another unexpected aspect is that the film was made in English. All of the Thammasat ajarns and students participating in 1940 had good enough English to act in a film in that language. The film was made for a specific purpose. Its theme was pacifism, or being against war, except in cases where invasion makes war unavoidable.

What happens in King of the White Elephant.

In 16th century Ayutthaya, King Chakra is urged by his Lord Chamberlain to marry over 300 wives, although the King is reluctant to do so. A potential invasion by Burmese troops leads King Chakra to try diplomatic discussions. When these do not work, he declares war against the invader. Pridi Banomyong, who was highly sophisticated and informed about political matters, wished to send out a message to the international community, one reason why he produced the film in English. King of the White Elephant was shown in New York and Singapore to English-speaking audiences. Its timely point was that as World War II was gradually involving every country, Thailand was a peace-loving country. Yet when threatened by invasion, Thailand would respond. Just over one year after the film was released, Thailand was occupied by Japanese troops. Pridi became a leader of the Free Thai Movement of resistance against the occupying forces.

The film’s legacy.

Restored and rereleased on DVD in 2005 by the Thai Ministry of Culture with Technicolor Thailand and the National Film Archive, The King of the White Elephant still ranks as the oldest surviving Thai full-length film. This makes the fact that it was filmed in English even more impressive. The restoration was based on a 16-mm print in the Library of Congress, Washington DC. The film’s 35-mm negative did not survive the wartime chaos in Thailand. A screening of the restored print was a highlight of the Phuket Film Festival in 2007, in the presence of Dusdi Banomyong, daughter of Pridi Banomyong. The film archivist and historian Dome Sukvong, head of the National Film Archive, labored for three years on the film’s restoration, which was awarded the Fellini Silver Medal from UNESCO.

Other films as part of Thai history.

As a point of comparison, the other film chosen as part of the 2005 national restoration project was The Boat House (Ruen Pae), a 1962 musical romance. It was directed by General Major Prince Bhanubandhu Yugala (พระเจ้าวรวงศ์เธอ พระองค์เจ้าภาณุพันธุ์ยุคล) (1910-1995), the noted film director, producer, and and author. The prince, whose nickname was Sadet Ong Chaiyai, was a grandson of HM King Chulalongkorn and uncle of the director Prince Chatrichalerm Yukol. A more light-hearted film than The King of the White Elephant, made in peacetime, The Boat House is about three men who live in a floating bamboo hut on a river. Their romances, often accompanied by popular songs, are the subject of this film. As Dome Sukvong pointed out in an article, Thailand has a long tradition of film appreciation:

The story of the cinema in Thailand began eighty-five years ago when S.G. Marchovsky brought some reels of “Lumiere” films and showed them in Bangkok on June 1897. Thailand’s first film was made in 1900 by the younger brother of King Rama V, and the year 1927 saw the start of the feature film industry in Thailand. Since then more than 100,000 kilometres of film and some 3,000 feature films have been produced in Thailand. We can be almost sure that more than half the footage of these films made in or brought into Thailand has been lost forever, while the other half is scattered in private collections, in forgotten corners of attics, garages, store-rooms and old movie theatres, with termites and rats as their only custodians. In 1980, I started to gather all the available data concerning Thai films and in one year I had amassed enough data about most of the films made in Thailand, or made by Thai nationals, between 1897 and 1945 to be able to start looking for the films themselves. In 1981, when this search started, I came across 50,000 feet (15,200 metres) of film in a very old railway go-down (warehouse). This footage had been shot by the State Railways of Thailand between 1922 and 1945. The originals were all black and white negatives made of nitrate film. At least half of this footage may not be in a condition to be salvaged. Hoping somehow to salvage the other half, I contacted the officials of the National Archive and asked them to approach the State Railways and have the film transferred to the Archive so that it could be salvaged and preserved. All the State Railway films are now kept in the Thai National Archive.

Since then we have been able to locate at least ten more sources of old films. Some of them had been lying forgotten for at least half a century. One interesting and important discovery came from a lady who happened to read a newspaper headline about my discovery of the State Railway films. She found forty reels of old films in a store-room in her house. Later she contacted me and we immediately recovered the films only to find that the 35mm black and white nitrate prints were in bad condition. These films were originally the personal effects of the late King Rama VII (1926-1935) who was known to enjoy movies and film-making. The films had come into the possession of her father who had at one time been a member of the King’s palace staff. Together we found forty reels of film each some 1,000 to 1,500 (300 to 450 metres) feet in length. Among them were films of the King’s personal and State activities, such as royal ceremonies and his trips in the South-East Asian Peninsula, to Europe and to the United States of America. The films in this category were made by film companies of the countries he was visiting. The visit to the United States, for example, was filmed by Paramount Pictures. There were also a number of films made personally by the King while visiting Japan, as well as some Hollywood silent features starring Douglas Fairbanks, the King’s favorite film star.

Since then we have been able to locate at least ten more sources of old films. Some of them had been lying forgotten for at least half a century. One interesting and important discovery came from a lady who happened to read a newspaper headline about my discovery of the State Railway films. She found forty reels of old films in a store-room in her house. Later she contacted me and we immediately recovered the films only to find that the 35mm black and white nitrate prints were in bad condition. These films were originally the personal effects of the late King Rama VII (1926-1935) who was known to enjoy movies and film-making. The films had come into the possession of her father who had at one time been a member of the King’s palace staff. Together we found forty reels of film each some 1,000 to 1,500 (300 to 450 metres) feet in length. Among them were films of the King’s personal and State activities, such as royal ceremonies and his trips in the South-East Asian Peninsula, to Europe and to the United States of America. The films in this category were made by film companies of the countries he was visiting. The visit to the United States, for example, was filmed by Paramount Pictures. There were also a number of films made personally by the King while visiting Japan, as well as some Hollywood silent features starring Douglas Fairbanks, the King’s favorite film star.

In this context, it is noteworthy that Pridi Banomyong was Minister of Finance when he produced The King of the White Elephant. As some admirers of the film have noted, it has a certain amount of comedy amid its serious messages. Some of the visual jokes seem influenced by the important tradition of silent film comedy, as when a drunken man has trouble climbing onto an elephant. These are intercut with footage of elephants and soldiers marching towards the camera. When the film was reviewed in The New York Times in 1941, the silent film influences may have troubled the critic, who also seemed puzzled about why the film was made in English:

An amusing cinematic oddity, interesting mainly because it is the first feature-length motion picture ever made in Thailand (Siam), was presented last night at the Belmont under the title of “The King of the White Elephant.” And just as you would expect of a first picture made in any land—made with native actors speaking English dialogue mechanically—… in its primitive quality lies a certain amount of charm and, indeed, of unintentional humor deriving from its juvenilities. “The King of the White Elephant” is, except for sound, about twenty-five years behind the times. And that is the one serious criticism which we presume to make. Why should a group of Siamese artists attempt to ape Hollywood in a picture about their land? Why should they take a simple story of rivalry between two ancient kings, one a peaceful elephant-lover and the other a martial bully, and dress it up with chases and battles in the manner of an American Western? True, their mounts are pachyderms instead of pintos—and that does make for an interesting variety of spectacle. But why shouldn’t a made-in-Siam picture be truly indigenous, played in pantomime, if need be, and as different from Hollywood formula as it could be made?

More aware of the real historical purpose of the film and its ambitious goals, Bangkok Post film critic Kong Rithdee wrote, as quoted on the Thai Film Journal website:

The context surrounding the making of that film is different from what we’re experiencing now. King of the White Elephant, in which the dialogue is entirely in English, was made specifically to show the international community that Thais are capable of peace and that war, though sometimes inevitable, leaves everybody hurt and in ruins.

In the same Bangkok Post article, Dusadee Banomyong explained about Pridi:

Father foresaw that when Germany invaded Poland, another World War was inevitable. He wrote The King of the White Elephant and made it into a movie – an English-language movie – with the aim of showing the world that Siamese people love peace, that the conflicts in war are between kings or heads of state, but not between the people.

(all images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and the Thai Film Foundation).