Ajarns and students often receive spam emails, but predatory publishing solicitations have a certain look. Here is an example of such an email from the Vassar College Library website:

Dear <student>,

According to the Vassar College’s electronic library, you submitted a paper entitled <thesis title> in the course of your postgraduate degree.

Since we are planning publications in this subject area, our editorial team would be glad to know whether you would be keen on publishing the above mentioned work with us.

<publisher> Publishing is a member of an international group having nearly 10 years of experience in the publication of high-quality research works from well-known institutions worldwide.

For your information, all our books are available in printed form and marketed across the globe through more than 80,000 booksellers worldwide.

Kindly let know if you would be interested in receiving more detailed information in this respect.

I am looking forward to hearing from you.

Sincerely,

—

<editor’s name>

Acquisition Editor

The simple fact that a journal is writing to you should raise suspicions. What do they want? Clearly, in this case, they will ask you for money at some point. Ignore such spam emails or send them to the attention of people who are concerned with discouraging predatory publishers. Do your own research to identify periodicals which might want to publish your work. Some predatory publishers imitate the web design of real publishers quite closely, so it is important to look thoroughly at the website of any publication to which you are thinking of submitting material. Many universities make it clear that they will not fund the fees demanded by predatory websites, so it is especially important for all researchers to do their own checking to avoid this problem.

Other techniques of predatory publishers.

Some fake publishers are relatively easy to spot, because of the typographical errors on their websites and other danger signals. Others are far more sophisticated, as a 2013 article in Nature indicated. In that year, two serious European science journals were victims of identity theft. Fake websites were created for these journals which do not have their own real websites. Hundreds of researchers transferred payment to the false websites. Both charges writers over $500 USD, asking for wire transfers to banks accounts in Armenia. One the money was in Armenia, it became difficult to track further. The criminals reproduced such information on the false sites as the real journals’ titles, impact factors, postal addresses, and international standard serial numbers (ISSNs). The editor-in-chief of the real journal told Nature:

Victims are regularly contacting me to ask about the status of their papers: they transfer money and don’t see their papers published.

As a way of responding to this, both journals have increased their online presence so that internet searches for their publications will not continue to turn up the fraudulent sites. Yet these false sites were well-designed, to the point where at first even Thomson Reuters, the company producing the Scientific Citation Index and compiling journal impact factors, was deceived. Eventually, Thomson Reuters wrote to the Society of Physics and Natural History, asking why the print issues of their publication was so different from their website, and why the journal was only published twice a year, but the website claimed it appeared every month. At this point the fraud being clear, but even then, representatives of the false journal protested repeatedly when Thomson Reuters removed their link from a list of indexed publications, and researchers who had paid money to the fake site asked why their articles were not mentioned in Thomson Reuters indexes. Typically, the counterfeit websites announce many names of noted scientists on an editorial board. As it turns out, these scientists have no knowledge of the publication. Even when such sites are eventually closed down, often copycat sites appear in other countries.

Further complexities.

Sometimes scientific journals that were once serious become predatory, adding further difficulty for writers. This type of fraud suggests that even if you have heard of a journal, it is not just important to look carefully at its website. You should also:

- Check recent issues of the journal to make sure it is on the same high level as the journal you were familiar with.

- Do not transfer money to bank accounts located in unexpected countries with no connection to the place where the journal is supposed to be published.

Try not to figure all this out by yourself, alone. Discuss the subject with ajarns, students, librarians, and others before deciding where to submit research. Keep in mind the criteria established by Dr. Jeffrey Beall, who advises that researchers should beware when:

- The publisher’s owner is identified as the editor of all the journals published by the organization.

- No single individual is identified as the journal’s editor.

- The journal does not identify a formal editorial / review board.

- No academic information is provided regarding the editor, editorial staff, and/or review board members (institutional affiliation).

- Evident data exist showing that the editor and/or review board members do not possess academic expertise to reasonably qualify them to be publication gatekeepers in the journal’s field.

- Two or more journals have duplicate editorial boards (same editorial board for more than one journal).

- The journals have an insufficient number of board members, have concocted editorial boards (made up names), include scholars on an editorial board without their knowledge or permission, have board members who are prominent researchers but exempt them from any contributions to the journal except the use of their names and/or photographs.

- Or when the publisher…

- Demonstrates a lack of transparency in publishing operations.

- Has no policies or practices for digital preservation.

- Depends on author fees as the sole and only means of operation with no alternative, long-term business plan for sustaining the journal through augmented income sources.

- Begins operations with a large fleet of journals, often using a template to quickly create each journal’s home page.

- Provides insufficient information or hides information about author fees, offering to publish an author’s paper and later sending a previously-undisclosed invoice.

- Or when:

- The name of a journal is incongruent with the journal’s mission.

- The name of a journal does not adequately reflect its origin (a journal with the word “Canadian” or “Swiss” in its name that has no meaningful relationship to Canada or Switzerland).

- The journal falsely claims to have an impact factor, or uses some made up measure (view factor), feigning international standing.

- The publisher sends spam requests for peer reviews to scholars unqualified to review submitted manuscripts.

- The publisher falsely claims to have its content indexed in legitimate abstracting and indexing services or claims that its content is indexed in resources that are not abstracting and indexing services

- The publisher dedicates insufficient resources to preventing and eliminating author misconduct, to the extent that the journal or journals suffer from repeated cases of plagiarism, self-plagiarism, image manipulation, and the like.

- The publisher asks the corresponding author for suggested reviewers and the publisher subsequently uses the suggested reviewers without sufficiently vetting their qualifications or authenticity. (This protocol also may allow authors to create faux online identities in order to review their own papers).

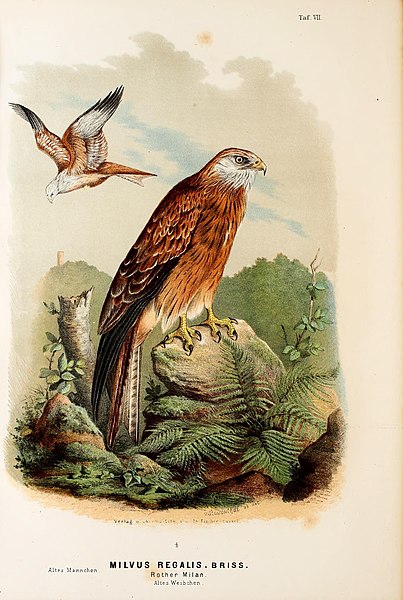

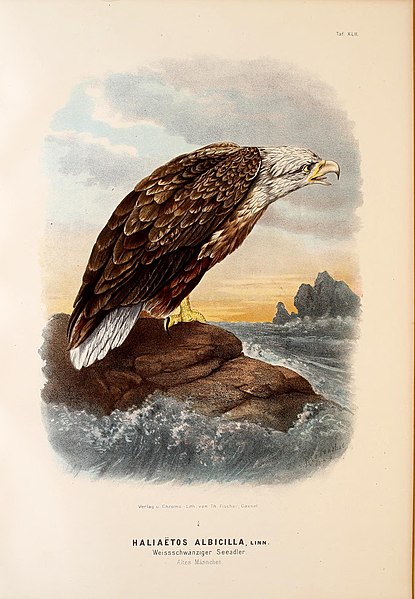

(all images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons).