A book newly donated to the Thammasat University Library should be of interest to students of political science, history, sociology, literature, education, and related fields. On the Underground 1 level of the Pridi Banomyong Library, Tha Prachan campus, The India Corner contains books generously donated by the Embassy of India in the Kingdom of Thailand, located in Thawi Watthana, Bangkok.

Great Speeches of Modern India, edited by Rudrangshu Mukherjee is shelved in the India Corner. While it offers many historical and political speeches by national leaders, it also has speeches by creative artists, notably by the Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray on cinema. The TU Library also owns some books about Satyajit Ray’s life and artistry.

Great Speeches of Modern India also contains a speech by the Indian poet and novelist Vikram Seth about his education. The TU Library owns copies of the poems and novels of Vikram Seth.

The editor of the anthology, Rudrangshu Mukherjee, is a professor of history and Chancellor of Ashoka University, a private research university with a focus on liberal arts, located in Sonipat, Haryana, India. The TU Library collection includes another book edited by Professor Mukherjee, The Penguin Gandhi Reader, also donated by the Embassy of India in the Kingdom of Thailand and shelved in The India Corner.

Professor Mukherjee has taught history at the University of Calcutta. He earned degrees from Presidency College, Kolkata, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, and St. Edmund Hall, Oxford. He received a Ph.D. in modern history from the University of Oxford.

He has written and edited many books on Indian history, which TU students may borrow by using the TU Library Interlibrary Loan (ILL) service.

In Great Speeches of Modern India, he suggests that although a good orator brings to a speech something more persuasive and moving than the power of the written word, nevertheless some public presentations retain their emotive charge on the printed page.

Leading speakers

Among such outstanding orators was the novelist R. K. Narayan, some of whose works are in the TU Library collection.

Born in Madras, Narayan was the son of a school headmaster. As a boy, he avidly read books by Charles Dickens, P. G. Wodehouse, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Thomas Hardy. Books by these writers are in the TU Library collection.

Narayan earned a bachelor of arts degree at Maharaja’s College, University of Mysore.

He briefly worked as a schoolteacher, but quit to become a writer after the headmaster insisted that he substitute for a gym instructor. Much later, when he serviced on a public council, he gave a much-remembered speech about how students were required to carry heavy school bags to educational institutions:

The hardship starts right at home when straight from bed the child is pulled out and got ready for school even before his faculties are awake. He or she is groomed and stuffed into a uniform and packed off with a loaded bag on her back. School bag has become an inevitable burden for the child. I am now pleading for abolition of the school bag by an ordiance. If necessary, I have investigated and found that an average child carries strapped to his back like a pack mule, not less than 6-8 kg. Of books, notebooks and other paraphernalia of modern education in addition to lunch box and water bottle. More children on account of this daily burden develop a stoop and hang their arms forward like a chimpanzee while walking and, I know some cases of serious spinal injuries of children too.

Another outstanding speech involving education was delivered by the Nobel Prizewinning Indian author Rabindranath Tagore. The TU Library owns several books by and about Tagore.

In My School, a lecture delivered in America in 1933, Tagore explained the philosophical basis for a place of learning that he had founded:

I started a school in Bengal when I was nearing forty. Certainly this was never expected of me, who had spent the greater portion of my life in writing, chiefly verses. Therefore people naturally thought that as a school it might not be one of the best of its kind, but it was sure to be something outrageously new, being the product of daring inexperience.

This is one of the reasons why I am often asked, what is the idea upon which my school is based. The question is a very embarrassing one for me, because to satisfy the expectation of my questioners, I cannot afford to be commonplace in my answer. However, I shall resist the temptation to be original and shall be content with being merely truthful…

And I know what it was to which this school owes its origin. It was not any new theory of education, but the memory of my school-days.

That those days were unhappy ones for me I cannot altogether ascribe to my peculiar temperament or to any special demerit of the schools to which I was sent. It may be that if I had been a little less sensitive, I could gradually have accommodated myself to the pressure and survived long enough to earn my university degrees. But all the same, schools are schools, though some are better and some worse, according to their own standard…

We have come to this world to accept it, not merely to know it. We may become powerful by knowledge, but we attain fulness by sympathy. The highest education is that which does not merely give us information but makes our life in harmony with all existence. But we find that this education of sympathy is not only systematically ignored in schools, but it is severely repressed. From our very childhood habits are formed and knowledge is imparted in such a manner that our life is weaned away from nature, and our mind and the world are set in opposition from the beginning of our days. Thus the greatest of educations for which we came prepared is neglected, and we are made to lose our world to find a bagful of information instead. We rob the child of his earth to teach him geography, of language to teach him grammar. His hunger is for the Epic, but he is supplied with chronicles of facts and dates. He was born in the human world, but is banished into the world of living gramophones, to expiate for the original sin of being born in ignorance. Child-nature protests against such calamity with all its power of suffering, subdued at last into silence by punishment…

But unfortunately for children their parents, in the pursuit of their profession, in conformity to their social traditions, live in their own peculiar world of habits. Much of this cannot be helped. For men have to specialize, driven by circumstances and by need of social uniformity.

But our childhood is the period when we have or ought to have more freedom-—freedom from the necessity of specialization into the narrow bounds of social and professional conventionalism.

I well remember the surprise and annoyance of an experienced headmaster, reputed to be a successful disciplinarian, when he saw one of the boys of my school climbing a tree and choosing a fork of the branches for settling down to his studies. I had to say to him in explanation that ‘childhood is the only period of life when a civilized man can exercise his choice between the branches of a tree and his drawing-room chair, and should I deprive this boy of that privilege because I, as a grown-up man, am barred from it?’ What is surprising is to notice the same headmaster’s approbation of the boys’ studying botany. He believes in an impersonal knowledge of the tree because that is science, but not in a personal experience of it. This growth of experience leads to forming instinct, which is the result of nature’s own method of instruction. The boys of my school have acquired instinctive knowledge of the physiognomy of the tree.

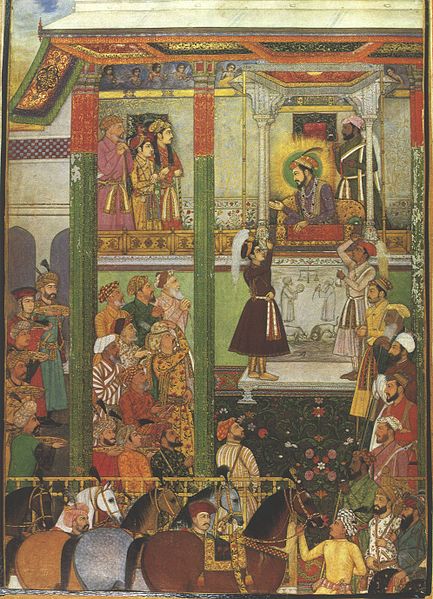

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)