Through the generosity of the late Professor Benedict Anderson and Ajarn Charnvit Kasetsiri, the Thammasat University Library has acquired some important books of interest for students of Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) studies, history, political science, literature, and related fields.

They are part of a special bequest of over 2800 books from the personal scholarly library of Professor Benedict Anderson at Cornell University, in addition to the previous donation of books from the library of Professor Anderson at his home in Bangkok. These items are shelved in the Charnvit Kasetsiri Room of the Pridi Banomyong Library, Tha Prachan campus.

These include the celebrated American novel, The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane (1871–1900). First published in 1895, The Red Badge of Courage is about the American Civil War. A young soldier runs away from a battlefield, but later fights courageously.

Stephen Crane died at the early age of 28, but is still remembered as a leading American author of his generation.

The TU Library collection includes a number of other books by and about Stephen Crane.

TU Faculty of Journalism and Mass Communication students may be interested to know that Crane worked as a newspaper reporter, including some time as a war correspondent after he wrote The Red Badge of Courage.

This is how Crane’s book ends:

The regiment marched until it had joined its fellows. The reformed brigade, in column, aimed through a wood at the road. Directly they were in a mass of dust-covered troops, and were trudging along in a way parallel to the enemy’s lines as these had been defined by the previous turmoil.

They passed within view of a stolid white house, and saw in front of it groups of their comrades lying in wait behind a neat breastwork. A row of guns were booming at a distant enemy. Shells thrown in reply were raising clouds of dust and splinters. Horsemen dashed along the line of intrenchments.

At this point of its march the division curved away from the field and went winding off in the direction of the river. When the significance of this movement had impressed itself upon the youth he turned his head and looked over his shoulder toward the trampled and debris-strewed ground. He breathed a breath of new satisfaction. He finally nudged his friend. “Well, it’s all over,” he said to him…

Over the river a golden ray of sun came through the hosts of leaden rain clouds.

Thailand and Stephen Crane

Stephen Crane’s father Jonathan Townley Crane (1819–1880) was an American clergyman, author, and anti-slavery activist.

Among his many writings was A Talk About Talk: or the Art of Talking, a lecture first delivered in 1868, four years before his son was born. This lecture is of interest to Thais because it contains evidence of Jonathan Townley Crane’s attitudes toward In and Chun (1811-1874), conjoined twins born in 1811 in the Mae Klong Valley, Samut Songkhram Province, Siam, during the reign of HM King Rama II.

Their father, Ti-aye, a fisherman, was of Chinese origin and their mother, Nok, possibly of Chinese-Malay background, so the boys were known as the Chinese twins in their homeland. Joined at the sternum by a piece of cartilage, the boys were athletic and enjoyed playing badminton and performing tumbling tricks despite their disability. This caught the eye of a traveling British merchant who exported them to America to exhibit them in sideshows.

Renamed Chang and Eng, they would later convert to Christianity and adopt the family name Bunker, as they settled down in North Carolina. They both married and had several children, some of whom fought for the Confederacy in the American Civil War. They became so famous as performers that a new term, Siamese twins, was used until fairly recently to describe conjoined twins.

Jonathan Townley Crane first made some general observations about the value and importance of talking, such as:

It is because it is natural to talk; because we love to talk; because however true, beautiful, or valuable ideas may be, they seem to lose half their value where there is no chance to tell them to somebody else.

Then he added:

It is said that the Siamese twins seldom speak to each other. Why should they? Chang sees what Eng sees. Eng knows all that Chang knows. What can they talk about? From kindred causes, the conversation of old friends, who meet daily, does not spur the intellect as when they first became acquainted. Still confidence is better than novelty; and what the autumn of friendship lacks of the budding beauty and bloom of spring, it more than compensates for in its stores of mellow fruit.

Chang and Eng Bunker, the Siamese Twins, lived until 1874, and they were still alive when Jonathan Townley Crane was speculating about them in public.

Perhaps because his father was aware of Siam, Stephen Crane also made reference to the Kingdom in his writings. His novel The Third Violet (1897) is a romantic narrative which mentions Asia, especially Siam and China, to evoke the exquisite nature of emotions felt by male and female characters. Crane describes a chandelier, gleaming like a Siamese headdress.

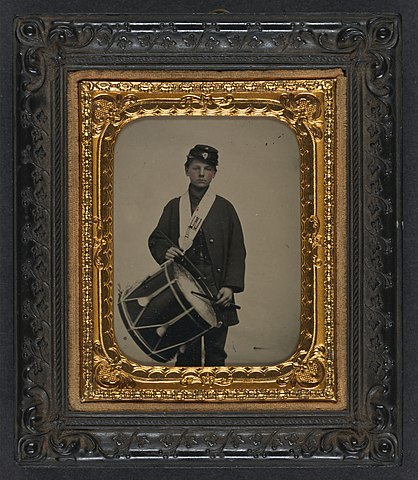

By the 1870s, postcards showing traditional Siamese garments, including headdresses, were popular in the West. Here is part of the relevant chapter of Crane’s novel with this image:

CHAPTER XXVI.

The harmony of summer sunlight on leaf and blade of green was not known to the two windows, which looked forth at an obviously endless building of brownstone about which there was the poetry of a prison. Inside, great folds of lace swept down in orderly cascades, as water trained to fall mathematically. The colossal chandelier, gleaming like a Siamese headdress, caught the subtle flashes from unknown places.

Hawker heard a step and the soft swishing of a woman’s dress. He turned toward the door swiftly, with a certain dramatic impulsiveness. But when she entered the room he said, “How delighted I am to see you again!”…

“I have always said that you should have been a Chinese soldier of fortune,” she observed musingly. “Your daring and ingenuity would be prized by the Chinese.”

“There are innumerable tobacco jars in China,” he said, measuring the advantages. “Moreover, there is no perspective. You don’t have to walk two miles to see a friend. No. He is always there near you, so that you can’t move a chair without hitting your distant friend. You——”

“Did Hollie remain as attentive as ever to the Worcester girls?”

“Yes, of course, as attentive as ever. He dragged me into all manner of tennis games——”

“Why, I thought you loved to play tennis?”

“Oh, well,” said Hawker, “I did until you left.”

“My sister has gone to the park with the children. I know she will be vexed when she finds that you have called.”

Ultimately Hawker said, “Do you remember our ride behind my father’s oxen?”

“No,” she answered; “I had forgotten it completely. Did we ride behind your father’s oxen?”

After a moment he said: “That remark would be prized by the Chinese. We did. And you most graciously professed to enjoy it, which earned my deep gratitude and admiration. For no one knows better than I,” he added meekly, “that it is no great comfort or pleasure to ride behind my father’s oxen.”

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)