Thammasat University students are cordially invited to participate in a free online lecture on Monday, 10 May about Cinema As Soft Power.

The lecture is organized by the Department of Comparative Literature, Centre for the Study of Globalization and Cultures and Centre for the Study of Globalization and Cultures, Hong Kong University (HKU).

The Thammasat University Library collection includes several books about the concept of soft power, a term used in international politics to describe the ability to attract and coopt, rather than coerce other nations into behaving a certain way.

Soft power involves shaping the preferences of others through appeal and attraction.

A defining feature of soft power is that it does not force anyone to do anything, but uses culture, political values, and foreign policies to achieve its goal.

The HKU website explains:

Event Details

This talk presents a case for studying cinema as a form of soft power and reflects upon the use of soft power as a method for studying cinema. Scholarship on soft power has been predominantly interested in tracing the effect of soft power generated by governmental agents’ initiatives upon foreign audiences. This talk brings the notion of affect into the equation to argue that affect functions as a mediating environment that underpins any cultural flow and communicative process. Moreover, it reverses the direction of cultural flow by suggesting that agency emanates from foreign audiences who, precisely because of their affective resonances with particular films, auteurs, stars, and genres, have initiated schemes, processes, and expressions that stand as concrete manifestations of cinematic soft power.

The speaker will be Professor Song Hwee Lim, Professor of Cultural Studies at The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The Thammasat University Library owns Professor Lim’s Celluloid comrades: representations of male homosexuality in contemporary Chinese cinemas.

It is shelved in the General Stacks of the Pridi Banomyong Library, Tha Prachan campus.

His book on the soft power of Taiwan cinema will be published by Oxford University Press next year.

Professor Lim earned a bachelor of arts degree in Chinese Literature from National Taiwan University, a Postgraduate Diploma in Education (PGDE) from Nanyang Technological University, and a master of philosophy degree and doctorate in Oriental Studies, both from Cambridge University, the United Kingdom.

The lecture will be at 10:30am Bangkok time.

Please register at this link.

A Zoom link will be sent to attendees one day before the event.

For any further questions, please feel free to contact Tilly Wong by email at tiwyw@hku.hk

The impact of soft power

The American political scientist Joseph Nye, a longtime professor at Harvard University, introduced the concept of soft power in the 1980s. If power is the ability to influence the others to get desired outcomes, this can be done by threats or payment, or by attracting people to do what is wanted.

Professor Nye locates soft power in attractive aspects of national culture, political values that are demonstrated at home and overseas, and foreign policy seen as legitimate and morally authoritative.

As Professor Nye wrote:

A country may obtain the outcomes it wants in world politics because other countries – admiring its values, emulating its example, aspiring to its level of prosperity and openness – want to follow it. In this sense, it is also important to set the agenda and attract others in world politics, and not only to force them to change by threatening military force or economic sanctions. This soft power – getting others to want the outcomes that you want – co-opts people rather than coerces them… Seduction is always more effective than coercion, and many values like democracy, human rights, and individual opportunities are deeply seductive.

Professor Nye admits that soft power is more difficult for governments to use than hard power, because many of its essential elements are outside government control. Also, soft power tends to work indirectly by shaping the environment for policy, and sometimes takes years to produce the desired outcomes.

In a chapter in The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas, Professor Lim wrote about Taiwan New Cinema: Small Nation with Soft Power.

Here is the abstract of that chapter:

How does one measure the significance of a nation’s cinema? This chapter presents a case for Taiwan cinema as a product of a small nation with enormous soft power. Tracing major awards won by Taiwan films and directors at international film festivals, it will show that a dismal domestic production level is no hindrance to a small cinema’s global critical acclaim and examine the paradoxical dynamic between a perceived failure in the state of domestic film production and consumption and the undeniable prestigious international status of Taiwan cinema. Using as its focus the Taiwan New Cinema (TNC) movement that began in the early 1980s, this chapter advocates for “another kind of cinema” (a concept proposed during the TNC period) and explores the implications of this bifurcation for Taiwan film historiography.

Further academic research about cinema as a form of soft power may be seen in a project from the School of Languages, Cultures and Societies at the University of Leeds, the United Kingdom: Soft Power, Cinema and the (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) BRICS describe the effect of film in five major emerging economies.

As the University of Leeds website explains, the project studies

the implications for global film culture of the apparent shift in power relations between the developed and developing world, along with the increasing emphasis national and transnational organisations place on the role of ‘soft power’ in global foreign policy, focussing specifically on the BRICS. Individual members of this group, most obviously China and India, have been much discussed in this context. However, the diverse, and often competing ways the group as a whole engages with film as a medium of artistic expression, on the one hand, and a soft power ‘resource’ on the other, along with the wider implications for world cinemas of its members’ very different, and dynamic, positions within the global media landscape, remain to be investigated comparatively.

The project is timely, given the following: soft power is an explicit element of the current (2012 start) Chinese government five-year plan; one of the EU’s strategic objectives is to promote culture as a vital element of EU international relations; and the first report of the UK House of Lords Select Committee on Soft Power and the UK’s influence (‘Persuasion and Power in the Modern World’) was published last year (2014) and was widely commented on in the international press. As well as drawing on evidence from representatives of British commercial interests, culture industry representatives and academics (including members of Leeds’ Centre for World Cinemas), the committee made reference to the so-called ‘rise of the rest’ and very notably sought and reproduced information on soft power issues relating to BRICS countries (especially China and Brazil). Thus the time is clearly ripe to explore in greater detail the employment of soft-power strategies by emerging nations, in order to nuance discussions on what successful soft power ‘looks like’ in different parts of the globe, and by providing analysis from the perspective of film culture.

The network builds on both the connections established and the research findings of a World Universities Network-supported project entitled Film Policy, Cultural Diplomacy and Soft Power (2012-2014), which brought together scholars working on cultural policy issues relating to soft power in China, Hong Kong, Denmark, South Africa, Brazil and the UK, with a focus on how policymakers seek to achieve soft power objectives, and how they negotiate artistic, economic and political networks.

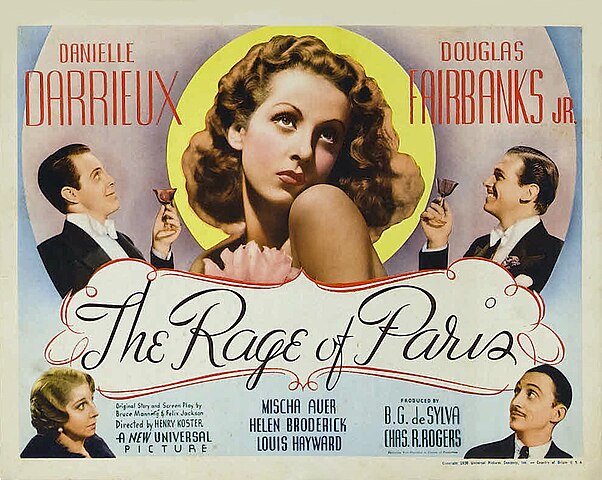

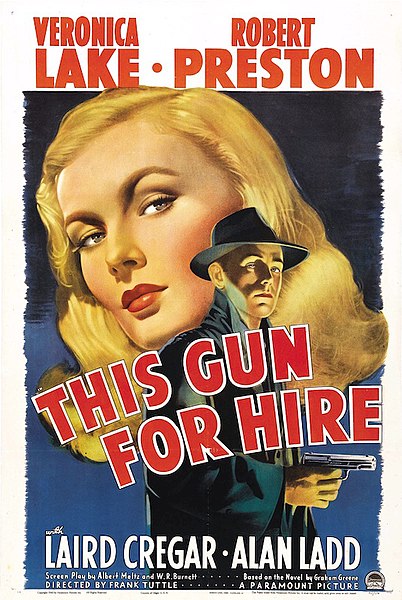

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)