The Thammasat University Library has acquired a new book that may be useful for students interested in media and communications, science, and related subjects.

Doctor Who and Science: Essays on Ideas, Identities and Ideologies in the Series is shelved in the General Stacks of the Pridi Banomyong Library, Tha Prachan campus.

It is a collection of essays edited by Associate Professor Marcus K. Harmes, who teaches at the University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Australia, and Dr. Lindy A. Orthia, a senior lecturer in science communication at the Australian National University in Canberra.

Its subject is Doctor Who, a British science fiction television program broadcast by BBC One since the early 1960s.

The TU Library collection also includes other books which examine the international cultural impact of the Doctor Who program.

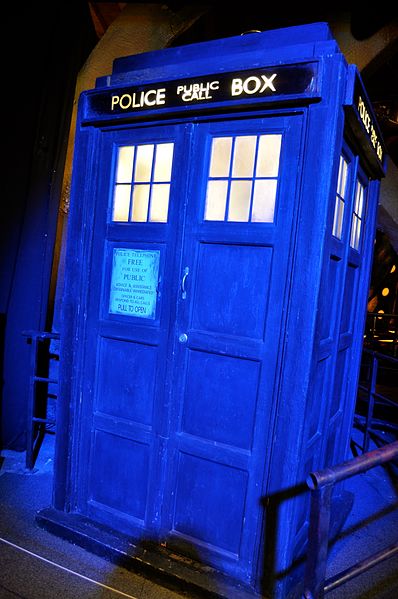

The show is about adventures of an extraterrestrial being known as the Doctor, who travels through time across the universe in a space ship called the TARDIS.

The Doctor fights enemies and works to save civilizations.

Science has been a significant part of Doctor Who, and many children in the United Kingdom (UK) who grew up to be scientists state that their interest in science was awakened by the program.

Doctor Who and Science discusses the show’s approach to such research studies as astronomy, genetics, linguistics, computing, history, sociology and science communication.

Fans of the series are sometimes called Whovians.

It is considered the longest-running science fiction television show in the world.

Thailand has long been interested in Doctor Who, as the Kingdom was the first non-Commonwealth country, and first non-English-language nation to screen the series on 20 August 1966.

In 2019, Dr. Lindy A. Orthia published an overview of how Doctor Who shapes public attitudes to science:

As long ago as 1985, Britain’s Royal Society wondered whether they could use Doctor Who to promote greater public understanding of science.

Given that we care so much, one might expect to see strong evidence that Doctor Who shapes how its viewers think and feel about science. But there has been no peer-reviewed research in this area, only anecdotes from a few scientist-fans.

Until now.

In my research, published in the Journal of Science Communication, I surveyed 575 science-interested Doctor Who viewers, asking whether and how the show contributed to their relationship with science.

Many of them said it did. But as it turns out, not in consistent ways.

Thoughts about science

I recruited the 575 people via ScienceAlert; they were 59% female, 40% male and 1% non-binary or gender-fluid. They were aged 18-73, and were drawn from 37 nations, predominantly Australia (50%) and the United States (24%).

Of the 575 respondents, 398 said Doctor Who influenced their thoughts about science in one way or another.

Just over 300 respondents said the show contributed to their ideas about science ethics, the relationship between science and the rest of society, and/or the place of science in human history.

Most commonly, Doctor Who prompted people to think more deeply about the ethics of science, including its moral ambiguity and potential for doing both good and bad. Second to that, many said Doctor Who demonstrated science’s importance in society and history.

However, individual participants sometimes drew opposite conclusions about the show’s moral messages. For example, one participant said their take-home message from Doctor Who on science ethics was:

Strong ethical guidelines and laws need to exist, and be enforced.

But for another participant it was precisely the opposite:

We should stop putting ethics in the way of scientific research.

Choosing science

Beyond shaping people’s attitudes, Doctor Who had a material impact on a few people’s life choices too.

It influenced 74 participants’ education choices and 49 participants’ career choices. It sparked interest in pursuing diverse science (and other) fields including physics, astronomy, maths, engineering, computer science, environmental science, chemistry, psychology, science teaching, and science communication.

People said things like:

It made me want to learn more about science. I became a science major [because] of it.

And:

I have a degree in Environmental Science specifically because of watching the 4th Doctor deal with oil rigs. That and the Exxon Valdez made me want to change things.

Some respondents said Doctor Who simply instilled a love of learning in them or made them proud of achieving academic success.

Just a TV show?

The survey responses go far beyond the previous anecdotes from fans about how much they love science and Doctor Who. It gives us lots of new evidence to analyse – some 58,000 words of qualitative data. But the responses were far from unanimously positive.

In the survey group, 107 people answered “no” to all or most of my key questions, indicating Doctor Who had not contributed to their relationship to science in any of the ways I asked about.

They gave a range of reasons. Some came to Doctor Who too late, after their views on science had already formed. Or other factors such as school or family determined their attitudes to science and life decisions, so Doctor Who wasn’t important (gasp!).

Others were more cynical, generally mocking the notion of science fiction influencing them at all, or arguing that Doctor Who’s depictions of science were too inaccurate, fantastical or trivial to have an impact.

Some responses were neither particularly positive or negative, with Doctor Who simply validating or reinforcing people’s existing ideas about science.

So will Doctor Who create a planet of scientists?

Part of the job for some science communicators, science teachers and scientists is to inspire people’s interest in science.

My study shows that engaging with a science-rich television program can have a profoundly inspiring effect on a person’s attitudes to science. In fact, their life might be changed because of it.

If that kind of inspiration is your goal, it is worth investing in science-rich television fiction as a science engagement medium.

But don’t get too excited. Not everyone’s science attitudes are affected by the same program. Any positive effects may be minor, rather than life-changing. And two viewers may interpret the science on screen in completely different ways. Also, my participants volunteered to participate, so the numbers don’t necessarily represent statistical patterns among Doctor Who viewers generally.

This backs up what science communication researchers have been saying for years. Television audiences aren’t ignorant dupes brainwashed by what they watch. People watch television fiction critically, aware it is fiction. All of us bring our existing knowledge, beliefs, fears and ideals to the viewing experience and make our own meanings from it in light of them.

What science-rich fiction can do, though, is set an agenda. It can offer people new frameworks for pondering science questions and provoking conversations about them.

So despite the caveats, if we want to nurture a society of people who think about science more keenly, more critically and more often, we could do worse than plug the next season of Doctor Who.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)