The Thammasat University Library has newly acquired a book that should be useful for students interested in philosophy, comparative religion, ethics, mathematics, and related subjects.

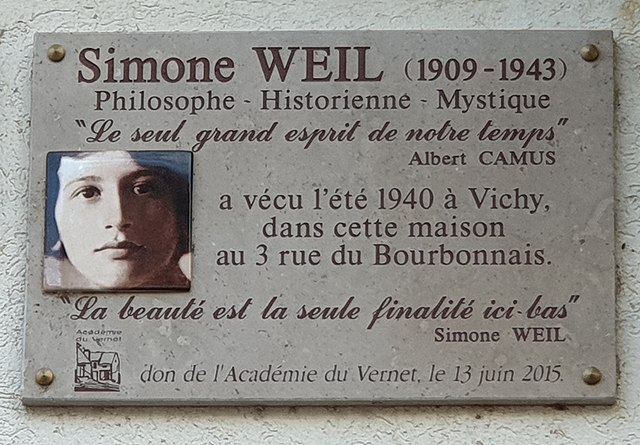

At Home with André and Simone Weil is a memoir by the niece of the French philosopher, mystic, and political activist Simone Weil (1909–1943).

It also discusses the mathematician André Weil, the brother of Simone Weil.

The TU Library collection includes a number of books by and about Simone Weil.

As a philosopher, she was noted for seeking truth and justice.

At different times she worked in a factory, to understand how working class people felt, and tried to eat as little as impoverished people when food was scarce during wartime.

She was a skilled translator of ancient Greek texts and Pythagorean geometry formulas.

She also offered advice to political, industrial, and religious leaders as well as university students, factory workers, and farm laborers.

The author André Gide, who is also represented in the TU Library collection, called her the patron saint of all outsiders.

The Italian philosopher, Giorgio Agamben, whose works are also owned by the TU Library, praised her conscience as “the most lucid of our times.”

The German-born American political theorist Hannah Arendt stated that perhaps only Weil discussed the subject of labor “without prejudice and sentimentality,”

Pope Paul VI claimed that Simone Weil was one of his three greatest influences.

Some writers, like T. S. Eliot, Dwight Macdonald, Leslie Fiedler, and Robert Coles have called her a saint.

In recent years, academic research into the life and writings of Simone Weil have applied her ideas to such different fields as classical studies, cultural studies, education and technical fields like ergonomics.

Some critics have pointed out that Weil’s opinions are often extreme and uncompromising.

General Charles de Gaulle, for whom she worked in the French Resistance movement during the Second World War, considered her “insane.”

Here are some thoughts by Simone Weil, from books available at the TU Library:

- Art is the symbol of the two noblest human efforts: to construct and to refrain from destruction.

The Pre-War Notebook (1933-1939), published in First and Last Notebooks (1970)

- I have sometimes told myself that if only there were a notice on church doors forbidding entry to anyone with an income above a certain figure, and a low one, I would be converted at once.

Letter to Georges Bernanos (1938), in Seventy Letters (1965)

- Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.

From an April 13, 1942 letter to poet Joë Bousquet, published in their collected correspondence (1982)

- Culture is an instrument wielded by professors to manufacture professors, who, when their turn comes, will manufacture professors.

The Need for Roots (1949)

- Love is not consolation, it is light.

As quoted in Simone Weil (1954)

- Whenever one tries to suppress doubt, there is tyranny.

Lectures in philosophy (1959)

- The human soul has need of truth and of freedom of expression.

The need for truth requires that intellectual culture should be universally accessible, and that it should be able to be acquired in an environment neither physically remote nor psychologically alien.

In order to be exercised, the intelligence requires to be free to express itself without control by any authority. There must therefore be a domain of pure intellectual research, separate but accessible to all, where no authority intervenes.

The human soul has need of some solitude and privacy and also of some social life.

The human soul has need of both personal property and collective property.

Whenever a human being, through the commission of a crime, has become exiled from good, he needs to be reintegrated with it through suffering. The suffering should be inflicted with the aim of bringing the soul to recognize freely some day that its infliction was just. This reintegration with the good is what punishment is. Every man who is innocent, or who has finally expiated guilt, needs to be recognized as honourable to the same extent as anyone else.

The human soul has need of disciplined participation in a common task of public value, and it has need of personal initiative within this participation.

The human soul has need of security and also of risk. The fear of violence or of hunger or of any other extreme evil is a sickness of the soul. The boredom produced by a complete absence of risk is also a sickness of the soul…

Imaginary evil is romantic and varied; real evil is gloomy, monotonous, barren, boring. Imaginary good is boring; real good is always new, marvelous, intoxicating…

There is nothing that comes closer to true humility than the intelligence. It is impossible to feel pride in one’s intelligence at the moment when one really and truly exercises it.

First and Last Notebooks (1970)

- Physical labour may be painful, but it is not degrading as such. It is not art; it is not science; it is something else, possessing an exactly equal value with art and science, for it provides an equal opportunity to reach the impersonal stage of attention…

If a captive mind is unaware of being in prison, it is living in error. If it has recognized the fact, even for the tenth of a second, and then quickly forgotten it in order to avoid suffering, it is living in falsehood. Men of the most brilliant intelligence can be born, live and die in error and falsehood. In them, intelligence is neither a good, nor even an asset. The difference between more or less intelligent men is like the difference between criminals condemned to life imprisonment in smaller or larger cells. The intelligent man who is proud of his intelligence is like a condemned man who is proud of his large cell.

The Self (1947)

- Liberty, taking the word in its concrete sense, consists in the ability to choose.

The Great Beast (1947)

- Prestige, which is illusion, is of the very essence of power…

“A man thinks he is dying for his country,” said Anatole France, “but he is dying for a few industrialists.” But even that is saying too much. What one dies for is not even so substantial and tangible as an industrialist…

What a country calls its vital economic interests are not the things which enable its citizens to live, but the things which enable it to make war; petrol is much more likely than wheat to be a cause of international conflict. Thus when war is waged it is for the purpose of safeguarding or increasing one’s capacity to make war. International politics are wholly involved in this vicious cycle. What is called national prestige consists in behaving always in such a way as to demoralize other nations by giving them the impression that, if it comes to war, one would certainly defeat them. What is called national security is an imaginary state of affairs in which one would retain the capacity to make war while depriving all other countries of it. It amounts to this, that a self-respecting nation is ready for anything, including war, except for a renunciation of its option to make war. But why is it so essential to be able to make war? No one knows, any more than the Trojans knew why it was necessary for them to keep Helen. That is why the good intentions of peace-loving statesman are so ineffectual. If the countries were divided by a real opposition of interests, it would be possible to arrive at a satisfactory compromise. But when economic and political interests have no meaning apart from war, how can they be peacefully reconciled?

Gravity and Grace (1947)

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)