The Thammasat University Library has acquired a new book that should be useful for students interested in British studies, literature, poetry, gender studies, history, sociology, and related subjects.

The Wife of Bath: A Biography is by Professor Marion Turner, who teaches English Literature and Language at the University of Oxford, the United Kingdom.

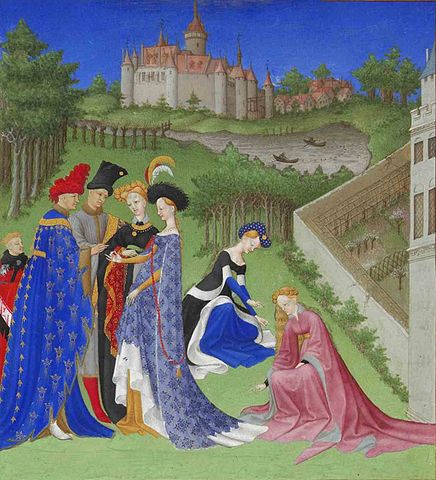

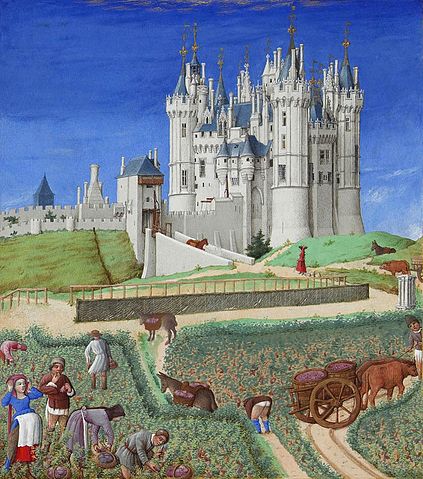

It is about a popular character in The Canterbury Tales, a long poem by the English poet Geoffrey Chaucer, who lived in the 1300s.

The TU Library collection includes many other books by and about Geoffrey Chaucer.

Here is the beginning of Chaucer’s long poem, in a modern English translation by Neville Coghill:

When in April the sweet showers fall

And pierce the drought of March to the root, and all

The veins are bathed in liquor of such power

As brings about the engendering of the flower,

When also Zephyrus with his sweet breath

Exhales an air in every grove and heath

Upon the tender shoots, and the young sun

His half-course in the sign of the Ram has run,

And the small fowl are making melody

That sleep away the night with open eye

(So nature pricks them and their heart engages)

Then people long to go on pilgrimages

And palmers long to seek the stranger strands

Of far-off saints, hallowed in sundry lands,

And specially, from every shire’s end

Of England, down to Canterbury they wend

To seek the holy blissful martyr, quick

To give his help to them when they were sick.

It happened in that season that one day

In Southwark, at The Tabard, as I lay

Ready to go on pilgrimage and start

For Canterbury, most devout at heart,

At night there came into that hostelry

Some nine and twenty in a company

Of sundry folk happening then to fall

In fellowship, and they were pilgrims all

That towards Canterbury meant to ride.

Professor Coghill wrote this about Chaucer:

He was a prodigious reader and had the art of storing what he read in an almost faultless memory. He learnt in time to read widely in Latin, French, Anglo-Norman, and Italian. He made himself a considerable expert in contemporary sciences, especially in astronomy, medicine, psychology, physics, and alchemy. There is, for instance, in The House of Fame a long and amusing account of the nature of sound-waves. The Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale (one of the best) shows an intimate but furiously contemptuous knowledge of alchemical practice. In literary and historical fields his favourites seem to have been Vergil, Ovid, Statius, Seneca, and Cicero among the ancients, and the Roman de la Rose with its congeners and the works of Dante, Boccaccio, and Petrarch among the moderns. He knew the Fathers of the Church and quotes freely and frequently from every book in the Bible and Apocrypha.

Another distinguished English writer, G.K. Chesterton, wrote about Chaucer:

Chaucer was capable of greatness even in the sense of gravity. We all know that Matthew Arnold denied that the medieval poet possessed this ‘high seriousness’; but Matthew Arnold’s version of high seriousness was often only high and dry solemnity. That Chaucer was, in that passage about Troilus, speaking with complete conviction and a sense of the greatness of the subject (which seem to me the only essentials of the real grand style) nobody can doubt who reads the following verses, in which he turns with terrible and realistic scorn on the Pagan gods with whom he had so often played. I have mentioned these matters first to show that Chaucer was capable of high seriousness, even in the sense of those who feel that only what is serious can be high. But for my part I dispute the identification. I think there are other things that can be high as well as high seriousness. I think, for instance, that there can be such things as high spirits; and that these also can be spiritual.

Now even if we consider Chaucer only as a humorist, he was in this very exact sense a great humorist. And by this I do not only mean a very good humorist. I mean a humorist in the grand style ; a humorist whose broad outlook embraced the world as a whole, and saw even great humanity against a background of greater things. This quality of grandeur in a joke is one which I can only explain by an example. The example also illustrates that clinging curse of all the criticism of Chaucer; the fact that while the poet is always large and humorous, the critics are often small and serious. They not only get hold of the wrong end of the stick, but of the diminishing end of the telescope; and take in a detail when they should be taking in a design. The Chaucerian irony is sometimes so large that it is too large to be seen. I know no more striking example than the business of his own contribution to the tales of the Canterbury Pilgrims. A thousand times have I heard men tell (as Chaucer himself would put it) that the poet wrote The Rime of Sir Topas as a parody of certain bad romantic verse of his own time. And the learned would be willing to fill their notes with examples of this bad poetry, with the addition of not a little bad prose. It is all very scholarly, and it is all perfectly true; but it entirely misses the point. The joke is not that Chaucer is joking at bad ballad-mongers; the joke is much larger than that. To see the scope of this gigantic jest we must take in the whole position of the poet and the whole conception of the poem.

The Poet is the Maker; he is the creator of a cosmos; and Chaucer is the creator of the whole world of his creatures. He made the pilgrimage; he made the pilgrims. He made all the tales that are told by the pilgrims. Out of him is all the golden pageantry and chivalry of the Knight’s Tale; all the rank and rowdy farce of the Miller’s; he told through the mouth of the Prioress the pathetic legend of the Child Martyr and through the mouth of the Squire the wild, almost Arabian romance of Cambuscan. And he told them all in sustained melodious verse, seldom so continuously prolonged in literature; in a style that sings from start to finish. Then in due course, as the poet is also a pilgrim among the other pilgrims, he is asked for his contribution. He is at first struck dumb with embarrassment and then suddenly starts a gabble of the worst doggerel in the book. It is so bad that, after a page or two of it, the tolerant innkeeper breaks in with the desperate protest of one who can bear no more, in words that could be best translated as ‘Gorlummel’ or ‘This is a bit too thick!’ The poet is shouted down by a righteous revolt of his hearers, and can only defend himself by saying sadly that this is the only poem he knows.

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)