Thammasat University students interested in literature, British studies, sociology, history, and related subjects may find a book useful.

Dickens After Dickens is an Open Access book available for free download at this link:

https://universitypress.whiterose.ac.uk/site/books/e/10.22599/DickensAfterDickens/

It is edited by Dr Emily Bell, lecturer in digital humanities & digital skills at the School of English, University of Leeds, the United Kingdom.

The Thammasat University Library collection includes other books about different aspects of the life and work of Charles Dickens.

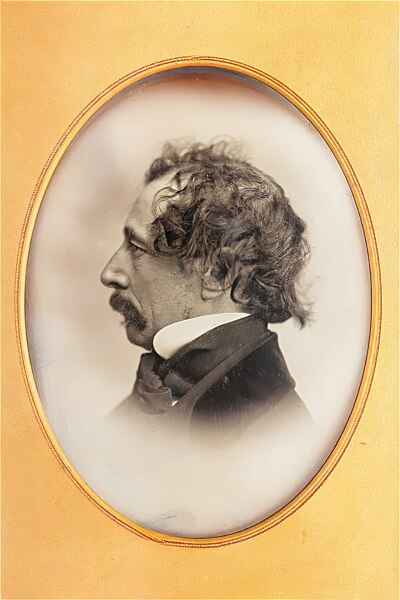

Charles Dickens was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and social critic.

His works enjoyed unprecedented popularity during his lifetime and are still adapted as films and television miniseries today.

Through his literary work, Dickens campaigned for children’s rights, education and other social reforms.

His 1843 novella A Christmas Carol remains popular and continues to inspire adaptations in every creative medium.

Oliver Twist and Great Expectations are also frequently adapted and, like many of his novels, evoke images of early Victorian London.

His 1859 novel A Tale of Two Cities (set in London and Paris) is his best-known work of historical fiction.

His work inspired many different critical reactions.

The author G.K. Chesterton wrote about Dickens:

He was the voice in England of this humane intoxication and expansion, this encouraging of anybody to be anything.

His best books are a carnival of liberty, and there is more of the real spirit of the French Revolution in “Nicholas Nickleby” than in “The Tale of Two Cities.” His work has the great glory of the Revolution, the bidding of every man to be himself; it has also the revolutionary deficiency: it seems to think that this mere emancipation is enough.

No man encouraged his characters so much as Dickens. “I am an affectionate father,” he says, “to every child of my fancy.” He was not only an affectionate father, he was an over-indulgent father. The children of his fancy are spoilt children. They shake the house like heavy and shouting schoolboys; they smash the story to pieces like so much furniture. When we moderns write stories our characters are better controlled.

But, alas! our characters are rather easier to control. We are in no danger from the gigantic gambols of creatures like Mantalini and Micawber. We are in no danger of giving our readers too much Weller or Wegg. We have not got it to give. When we experience the ungovernable sense of life which goes along with the old Dickens sense of liberty, we experience the best of the revolution. We are filled with the first of all democratic doctrines, that all men are interesting; Dickens tried to make some of his people appear dull people, but he could not keep them dull. He could not make a monotonous man. The bores in his books are brighter than the wits in other books. […]

Dickens overstrains and overstates a mood our period does not understand.

The truth he exaggerates is exactly this old Revolution sense of infinite opportunity and boisterous brotherhood. And we resent his undue sense of it, because we ourselves have not even a due sense of it. We feel troubled with too much where we have too little; we wish he would keep it within bounds. For we are all exact and scientific on the subjects we do not care about.

Some other opinions of Dickens by authors represented in the TU Library collection follow:

My own experience in reading Dickens…is to be bounced between violent admiration and violent distaste almost every couple of paragraphs, and this is too uncomfortable a condition to be much alleviated by an inward recital of one’s duty not to be fastidious, to gulp the stuff down in gobbets like a man.

- Kingsley Amis, What Became of Jane Austen? (1970)

Of Dickens, dear friend, I know nothing. About a year ago, from idle curiousity, I picked up The Old Curiousity Shop, & of all the rotten vulgar un-literary writing…! Worse than George Eliot’s. If a novelist can’t write, where is the beggar?

- Arnold Bennett, Letter to George Sturt, 6 February 1898

It does not matter that Dicken’s world is not lifelike; it is alive.

- David Cecil, Early Victorian Novelists (1934)

One of Dickens’s most striking peculiarities is that, whenever in his writing he becomes emotional, he ceases instantly to use his intelligence. The overflowing of his heart drowns his head and even dims his eyes; for, whenever he is in the melting mood, Dickens ceases to be able and probably ceases even to wish to see reality. His one and only desire on these occasions is just to overflow, nothing else. Which he does, with a vengeance and in an atrocious blank verse that is meant to be poetical prose and succeeds only in being the worst kind of fustian… Mentally drowned and blinded by the sticky overflowings of his heart, Dickens was incapable, when moved, of recreating, in terms of art, the reality which had moved him, was even, it would seem, unable to perceive that reality.

- Aldous Huxley. Collected Essays. Vulgarity in Literature.

The greatest of superficial novelists… It were, in our opinion, an offense against humanity to place Mr Dickens among the greatest novelists.

- Henry James, review of Our Mutual Friend in The Nation (21 December 1865)

There is a heartlessness behind his sentimentally overflowing style.

- Franz Kafka, diary entry (8 October 1917)

Not much of Dickens will live, because it has no little correspondence to life. He was the incarnation of cockneydom, a caricaturist who aped the moralist; he should have kept to short stories. If his novels are read at all in the future, people will wonder what we saw in them, save some possible element of fun meaningless to them. The world will never let Mr. Pickwick, who to me is full of the lumber of imbecility, share honors with Don Quixote.

- George Meredith, in Edward Clodd, Memories (1916)

In Oliver Twist, Hard Times, Bleak House, Little Dorrit, Dickens attacked English institutions with a ferocity that has never since been approached. Yet he managed to do it without making himself hated, and, more than this, the very people he attacked have swallowed him so completely that he has become a national institution himself. In its attitude towards Dickens the English public has always been a little like the elephant which feels a blow with a walking-stick as a delightful tickling. Before I was ten years old I was having Dickens ladled down my throat by schoolmasters in whom even at that age I could see a strong resemblance to Mr. Creakle, and one knows without needing to be told that lawyers delight in Sergeant Buzfuz and that Little Dorrit is a favourite in the Home Office. Dickens seems to have succeeded in attacking everybody and antagonizing nobody.

- George Orwell, in “Charles Dickens” (1939), also in Inside the Whale and Other Essays (1940)

One of the greatest books ever written in the English language was called Little Dorrit, and as soon as Englishmen realised that Little Dorrit was true there would be a revolution.

- George Bernard Shaw, in “Charles Dickens and Little Dorrit (1908)

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)