Thammasat University students interested in Japan, maritime history, sociology, anthropology, political science, and related subjects may find it useful to participate in a free 15 October Zoom book discussion on Oceanic Japan: The Archipelago in Pacific and Global History.

The event, on Tuesday, 15 October 2024 at 7pm Bangkok time, is presented by the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore (NUS).

The TU Library collection includes several books about different aspects of maritime Japan.

Students are invited to register at this link.

https://ari.nus.edu.sg/events/20241015-oceanic-japan/#form

The event announcement states:

Japan’s oceans demand our attention. Violent, prolific, and changeful, they define life and death on the archipelago: pushing the shore under the rush of tsunami, charging typhoon circulation, feeding millions, and seeding conflicts over territory and resources. And yet, Japan studies remain largely beholden to a terrestrial view of the world that is at odds with the importance of the sea. This “terrestrial bias” also means that on those occasions when oceans are recognized they are most often presented as dividers or connectors—spaces in between rather than rich ecologies and meaningful sites. Oceanic Japan is meant to help readers re-envision Japanese history in order to show how the seas created the country that we know today.

The book convenes a diverse, multinational, multidisciplinary group of scholars to expand the scope of Japan studies and the field of environmental humanities. The chapters draw from the broader turn to the sea—characterized by new oceanic and terraqueous perspectives—developing within these fields and in areas such as Pacific history and Indian Ocean studies. The volume editors’ vision is bifocal. On one hand, they aim to reorient East Asian studies and Japan studies to the sea, underlining how oceans have shaped dynamics from the Tokugawa Era forward into the age of empire and the crisis of the Anthropocene. On the other hand, they argue for a more nuanced environmental approach within the burgeoning field of Oceanic studies. Seeing oceanic spaces as more than entrepots or political spheres requires thinking in new, often vertical, volumetric ways. The chapters follow human and non-human actors to recognize the variegation of watery ecologies through winds, tides, coasts, seabeds, and currents such as the Kuroshio and Oyashio, which have always shaped life on the archipelago.

More information on the book can be found here: https://uhpress.hawaii.edu/title/oceanic-japan-the-archipelago-in-pacific-and-global-history/

ABOUT THE SPEAKERS

Stefan Huebner is a historian interested in environmental and oceanic topics whose work centers on modern Japan and its connections to other parts of Asia and the West. He is also Senior Research Fellow at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, and the President of the Society of Floating Solutions, Singapore. []…

Nadin Heé is Professor at Osaka University’s Graduate School of Humanities. […]

Ian J. Miller is Professor of History at Harvard University, where he teaches courses focused on Japan and its former empire, with special attention to questions of environment, science, and technology. […]

Bill Tsutsui has served as Chancellor and Professor of History at Ottawa University since 2021, after more than 30 years teaching modern Japanese history and holding a variety of administrative positions at the University of Kansas, Southern Methodist University, Hendrix College, and Harvard University. […]

Helen M. Rozwadowski is Professor of History and founder of the University of Connecticut’s Maritime Studies program. […]

Lijing Jiang is Assistant Professor at the Department of History of Science and Technology at Johns Hopkins University. […]

Gene Kim is a PhD candidate in History and East Asian Languages at Harvard University, focusing on modern Japanese and Korean history. […]

The forthcoming book Oceanic Japan: The Archipelago in Pacific and Global History will be available to TU students through the TU Library International Library Loan (ILL) service.

An afterword by Professor David Armitage, who teaches history at Harvard University, begins:

Oceanic historians have treated Japan as often as historians of Japan have engaged with the ocean: that is, remarkably rarely. As Alexis Dudden explains in this volume, Japan studies “are still bound by terrestrial over oceanic ways—ironic for an island nation.” It is ironic indeed because Japan can readily be described (as Paul Kreitman does, channeling Epeli Hau’ofa) as a sea of islands, a diverse assemblage of lands linked and formed by their surrounding waters.

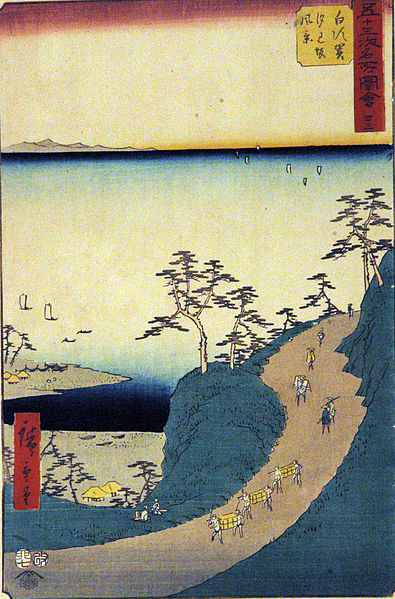

In the wake of UNCLOS, that oceanic expanse comprises the world’s eighth largest Exclusive Economic Zone, most of it spanning the ocean. The ocean bulks correspondingly large in the global imagination of Japan: Hokusai’s Great Wave is an icon of Japanese art; popular images place seafood at the heart of Japanese culture; and Japan’s major contribution to mythology is a monster from the deep, Godzilla. Moreover, it has had two heads of state, Emperor Hirohito and Emperor Naruhito, trained respectively in marine biology and maritime history.

Why, then, did the great wave of scholarship on oceanic history take so long to reach Japan? This conundrum has deep roots that are both historical and historiographical. One way to suggest the historical origins of the absence is to go back for a moment— not for the last time in this afterword—to the pivotal year of 1929. Only twenty-five years before, Japan had claimed naval pre-eminence and amazed the world by defeating Russia’s navy in the Russo-Japanese War.

Its commercial fishing fleet was already becoming the world’s largest and its reach was soon broad enough to make geopolitical waves around the north Pacific and as far away as Geneva and Washington, DC, as Sayuri Guthrie-Shimizu shows. For all that, Japan did not yet feature consistently on mental maps of oceanic power. One teasing sign of this came from a map produced almost 10,000 kilometers from Tokyo in Brussels by a group of Surrealists. “Le monde au temps des surréalistes” (1929) depicted a world out of kilter that was striking not least for setting the Pacific at the heart of the globe: a precedent for later maps designed to de-center the Atlantic. While it highlighted elements of Oceania like Easter Island and the Bismarck archipelago, it entirely omitted another archipelago in the “Ocean Pacifique”: Japan.

We must consider the source, of course: by definition, Surrealists did not strive to map conventional reality, but their insights often outran mere facts. In this case, a map focused on the ocean that overlooked Japan seems fitting because oceanic history has mostly ignored Japan. It is among this volume’s many achievements to have put Japan back on the map, oceanically speaking. […]

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)